6.14 Ricettari

The last part of this chapter (sections 6.16 - 6.19) will concern high-end how-to books aimed at teaching a particular professional skill, music. But the publishing norms and the economics of the market for such serious skills textbooks will be clearer if we first examine a few examples of a humbler genre, one aimed at the non-professional adult learner. For our purposes the catch-all form of the ricettario serves best to illumine how sixteenth-century authors adapted medieval antecedents in order to create a new genre.

The word ricettario literally means recipe book, but ricettari were not cookbooks in any modern sense. Their common element was that they offered formulas (ricetti) to solve everyday problems. Most often the formula involved making some sort of preparation appropriate to a particular ailment, beauty need, handyman's project, or self-improvement. The formulas often included superstitious or magical elements --actions or words unrelated to the practical mixing up of the glue, ointment. lotion, or powder. The formulas sometimes aimed more at creating a need than at solving a real-life problem. (78)

Medieval recipe collections were common and provided sources for most sixteenth-century ricettari. In the Middle Ages, such books were typically called books of secrets and they partook of the late-antique spirit of hermetic or arcane knowledge. Their authors took the magical dimensions of the recipes seriously. Since books of secrets were generally just collections of loosely related advices, their texts were highly unstable. At virtually every copying, a scribe could add or subtract material. For the most part, books of secrets did not have any direct relationship to the university-level science; they were mostly laymen's compendia. The readership for such books as a class was wide. (79)

The medieval book of secrets developed in two distinct directions, both resulting in books called ricettari in early modern Italy. Books systematically collected for the use of apothecaries and other medical workers could be called with this name, as in the case of the influential Ricettario fiorentino, first published in 1499 and enlarged and frequently reprinted with the sanction of the guild of physicians and spicers into the seventeenth century. These apothecaries' collections were both textbooks for teaching apprentices and also manuals for shop use. They were typically straightforward typographically and largely unadorned.

On the other hand, extracts from official recipe books and academic sources were combined with folklore to make up little booklets for layfolk also called ricettari. Ricettari of this latter sort became common in Italian cities from the fifteen twenties onward. Since they first appear in print in Italy at just the time when the first handwriting and arithmetic manuals were appearing, it is clear that printers modeled ricettari on small language and math textbooks. Printers offered the newly literate classes as many practical manuals as they could. Almost every booklet offered self-help and each claimed somehow to be "new," though few really broke new ground. Most assumed a deliberately conversational tone that seemed appropriate to their audience. (80)

.jpg)

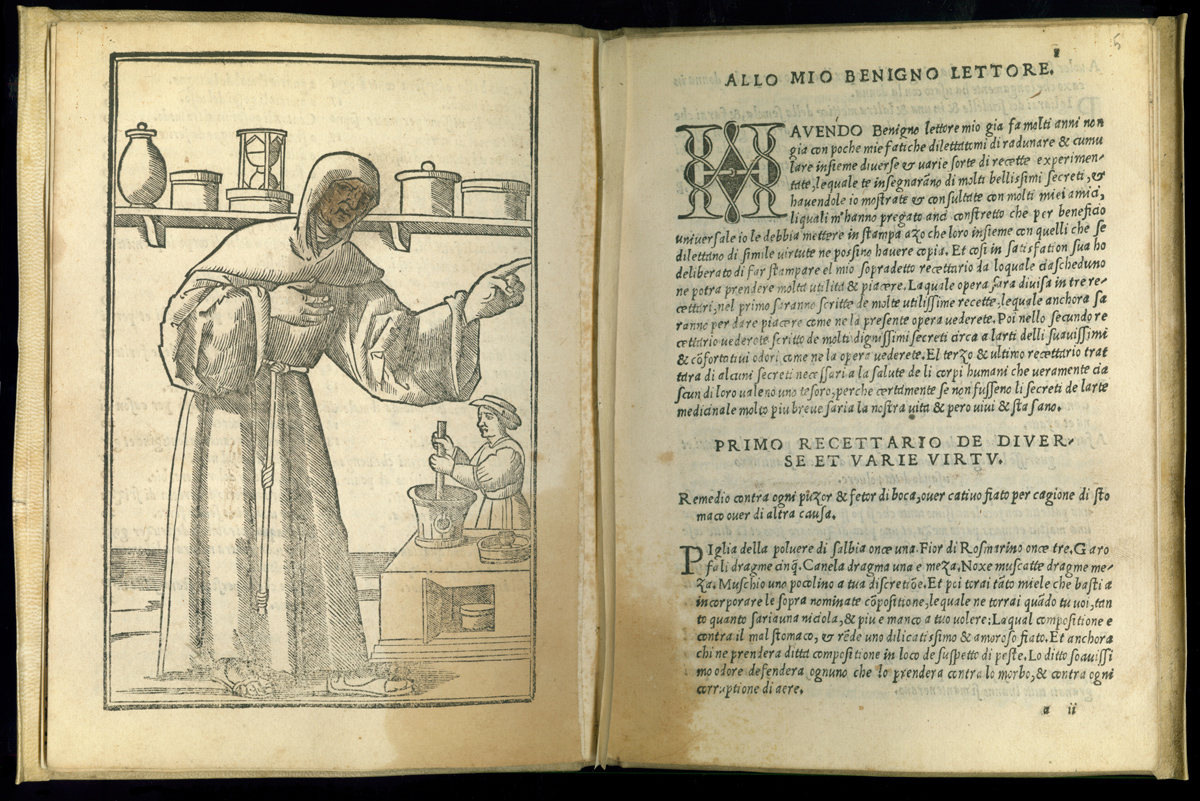

One much-reprinted ricettario was first issued at Venice in 1525 under the title Opera nuova intitulata, Dificio di ricette. (81) This Palace of Recipes is one of the better organized books of the sort, consisting almost entirely of really useful things: disinfectants, remedies for worms or fleas, tooth whiteners, vinegar substitutes. The title page advertised a book divided into three sections -- concoctions both useful and amusing, perfumes, and medicinal secrets. The recipes are largely devoid of magical or arcane formulas that were common in other books of the sort. There are a few harmless jokes too (candles that won't blow out, itching powder, an ointment to make a person's arm hairy); and the author frankly allowed as how he had not actually tested every recipe.

.jpg)

Though it was printed on the cheap, on poor paper with badly inked and broken types, this book was one of the best designed how-to books of the century. It is a broad, upright quarto (like handwriting books of the period, or humanist textbooks) which announced from the start that the book, though slender, is a serious compilation. In a 1528 issue, not only did the printer offer a good and accurate advertisement for the contents on the title page, he also displayed the title handsomely and gave the date of publication in enormous roman numerals to demonstrate that this was a more recent printing than rival ones on the market, whether in new or used copies. By emphasizing the date of printing in this way, moreover, he showed that he had no fear of the book staying in stock for very long. He could confidently expect to sell out and reprint again with another new date. The printer followed the handsome title page with a table of contents in clear, small italics that led the reader directly to the particular recipe she or he needed.

Each individual recipe was distinctly labeled with its title and a new paragraph opening, for easier reading and repeated consultation. At several points the small, closely set type is varied with woodcuts, and the specialized second and third sections have separate title pages. The printer has fully understood the design issues: first, that a recipe is a prescriptive formula that implies but does not enact a particular narrative; and second, that it is susceptible of repeated application, and so must be consulted, not just read once through.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (78) On the epistemology of the recipe, Eamon 1994, 131-134.

- (79) Serrai 1988, 338-343. Eamon 1994, 10-37; Bell 1999, 6-16.

- (80) The German equivalent was the Kunstbuchlein described by Eamon 1994, 112-126. Compare Bardi and other essays in Alambichi di parole 1999. On the conversational nature of ephemeral printing, McKenzie 1989, 101.

- (81) I describe it, and cite from, an edition of 1528 in a copy now at the Newberry Library. Other editions of 1529, 1530, 1534, 1543, 1546, 1550 are recorded by Ferguson, Eamon and Bardi; Eamon also describes how it was translated into French and Dutch and became a standard chapbook publication for centuries.