2.17 Desiderius Erasmus, Ad Man

It is well recognized that Erasmus was one of the most accomplished polemicists of the early sixteenth century, an able apologist and propagandist for his own worldview. Scholars are not in the habit of describing Erasmus as a marketing man, but some of his prefaces read remarkably like other advertising prose we have seen or will examine later in this book.

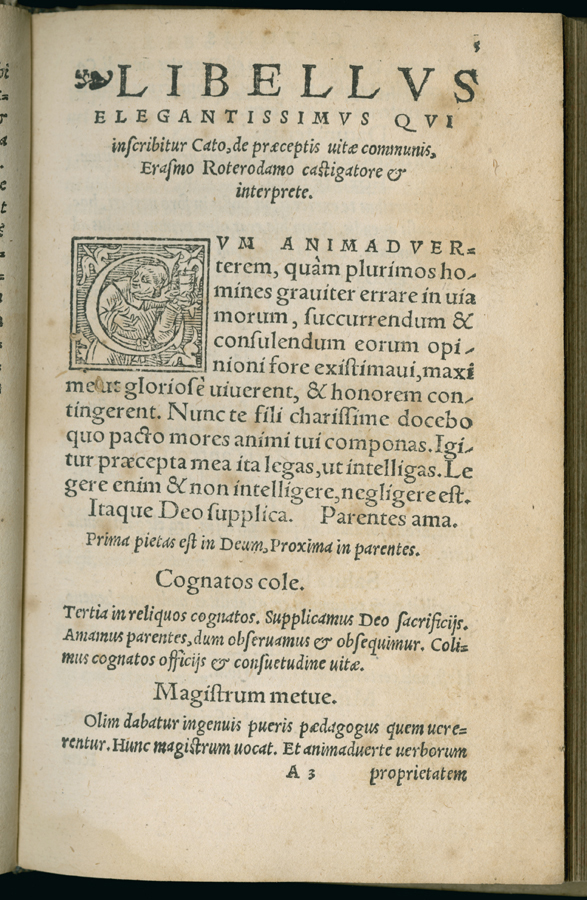

The best single example may be his thoughtful and well made revision of Pseudo-Cato which appeared from 1514 onward under the title Cato's Moral Distichs in Latin and Greek with Annotations by Erasmus (Catonis Disticha Moralia Latine et Graece, cum scholiis D. Erasmi Rotterdami). This booklet was one of several textbooks Erasmus published in 1514, probably as a money-making expedient. (103) It is a new package for the Cato, including the familiar distichs with the base text as corrected by Josse Bade, further tweaked by Erasmus, and enhanced by a paraphrase commentary. But, as ad men say, there is also much much more: a medieval translation of the Cato into Greek by Maximus Planudes (ca. 1230-ca. 1310) designed for Byzantine schoolboys and here edited by Erasmus; three other small collections of philosophers' sayings; Erasmus's poem on Christian education; and the Paraenesis of Isocrates, a collection of hortatory commonplaces. This package was offered for relatively young readers; but, since the texts are in both Latin and Greek, it seems likely that Erasmus also intended it for use in schools across several years. Like many other basic schoolbooks, this reading anthology sets up the expectation that it will be a useful moral reference life-long, both because it will be memorized in part and again because it would become a pocket book for future consultation. (104)

This Cato represents, moreover, a small installment in Erasmus's ongoing project of collecting and commenting proverbs, his Sayings (Adagia), which first appeared in 1500 and was continuously revised and enlarged until his death. The Adagia began as a sort of schoolbook too, as did another many-times-revised phrase book, On Abundance of Words and Things (De utraque rerum ac verborum copia). Modern critics have recognized that for Erasmus the proverb or adage was an historically situated literary artifact that could be immensely fruitful both of eloquence and of wisdom. Erasmus's Cato remained an elementary schoolbook, in keeping with its traditional place in the curriculum, while the De copia and the Adagia multiplied beyond their original dimensions into full-fledged monuments of humanist erudition. All three books stood in the tradition of rhetorical study as a pursuit of wisdom. Aphorisms and proverbs especially were closely associated with moral philosophy and with a tradition of prayerful meditation. In humanist hands the ethically succinct proverb could expand almost to a moral infinity. Even a teaching tool of the most elementary sort had this potential, and Erasmus' version of the Cato was already an expanded collection. (105)

There is little doubt that Erasmus himself devised the precise outline of the new Cato, although Lisa Jardine has argued convincingly that it also represents a collaboration with theologian Maarten van Dorp (1485-1525). (106) The preface begins:

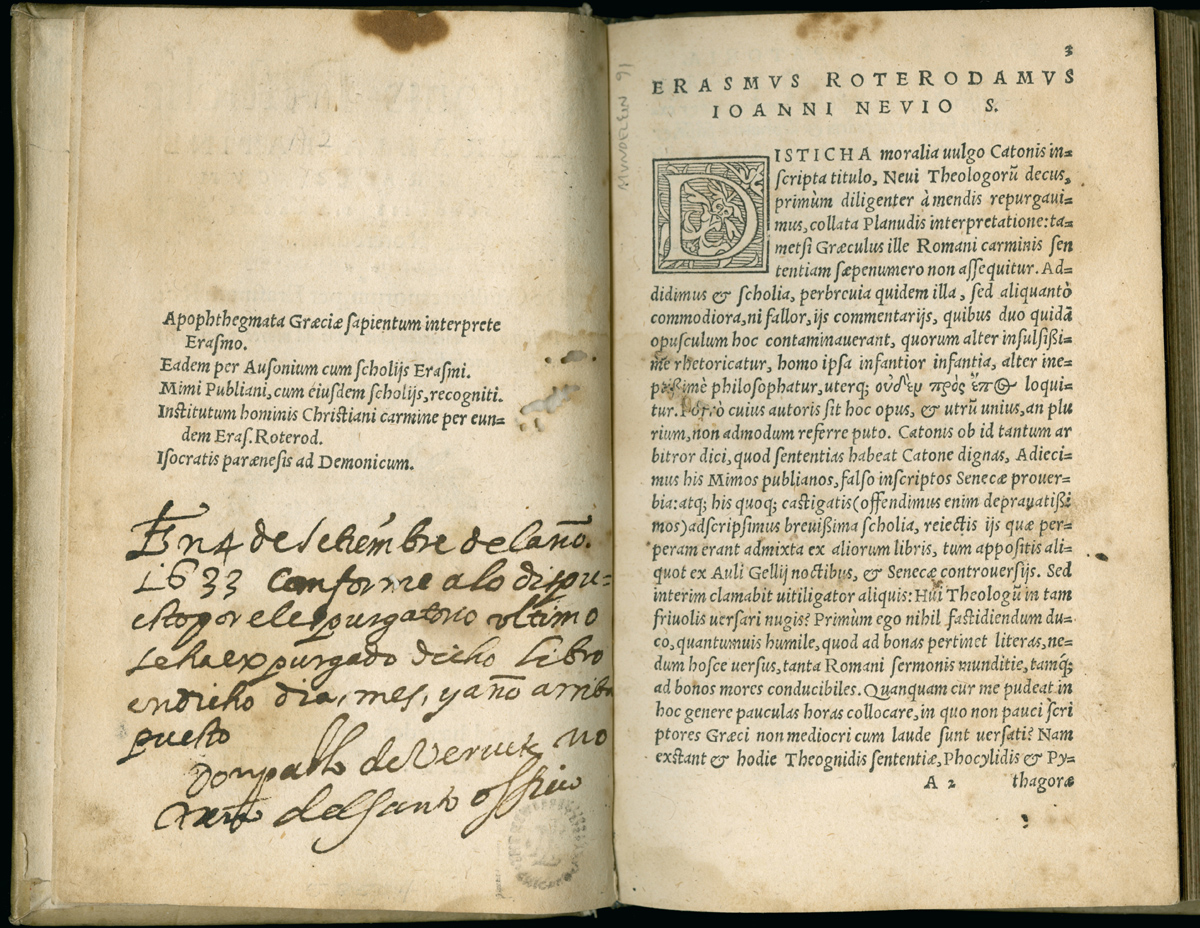

Erasmus of Rotterdam to Jan de Neve, greeting. The moral distichs commonly ascribed to Cato, O Nevius glory among theologians, we first purged of their errors by comparing them to the translation of Planudes, even if that little Greek frequently did not follow the sense of the Roman poem. We added also annotations which though very brief are somewhat more useful, if I am not mistaken, than the two commentaries with which certain men have hitherto contaminated this little work. One of those commentators, more idiotic than idiocy itself, pontificates like a fool; the other philosophizes ineptly. But neither says anything to the point. (107)

Any modern ad man would recognize some classic strategies here. Praise the product. Praise the packaging. When possible, slam the competition.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (103) Perraud 1988, 84. An important study of Erasmus and his printers is Vanautgaerden 2008.

- (104) Perraud 1988, 85-86; Thompson and Perraud 1990, 55-58; Jardine 1993, 113-115; Jensen 1996a, 72.

- (105) Erasmus 1978, 280-283; Greene 1986, 8-15; Jardine 1993, 42-45; Cherchi 1998, 53-58; Jeanneret 2001, 207-212, 248-252; Bisello 1998, xii-xix, 33-45.

- (106) Jardine 1993, 113-115.

- (107) Erasmus 1538, 3: Erasmus Roterodamus Ioanni Nevio S. Disticha moralia uulgo Catonis scripta titulo, Neui Theologorum decus, primum diligenter a mendis, repurgauimus, collata Planudis interpretatione tametsi Graeculus ille Romani carminis sententiam saepenumero non assequitur. Addidimus & scholia, perbreuia quidem illa, sed aliquanto commodiora, ni fallor, iis commentariis, quibus duo quidam opusculum hoc contaminaverant, quorum alter insulsissime rhetoricatur, homo ipsa infantior infantia, alter ineptissime philosophatur, uterque [in Greek:] ouden pros epos loquitur.