1.13 More and More Advertising

Most octavo Terences of the early sixteenth century (excepting only that of quirky Soardi) remarked their editors on the title pages and included prefatory letters or dedications in humanist style. But octavo editions offered little else by way of apparatus until the fifteen forties when marginalia began to appear. Contemporary folios were much more complex internally and offered more room on the title page for advertisements. In all formats, however, more and more advertising prose came to be crowded onto the title pages. (60)

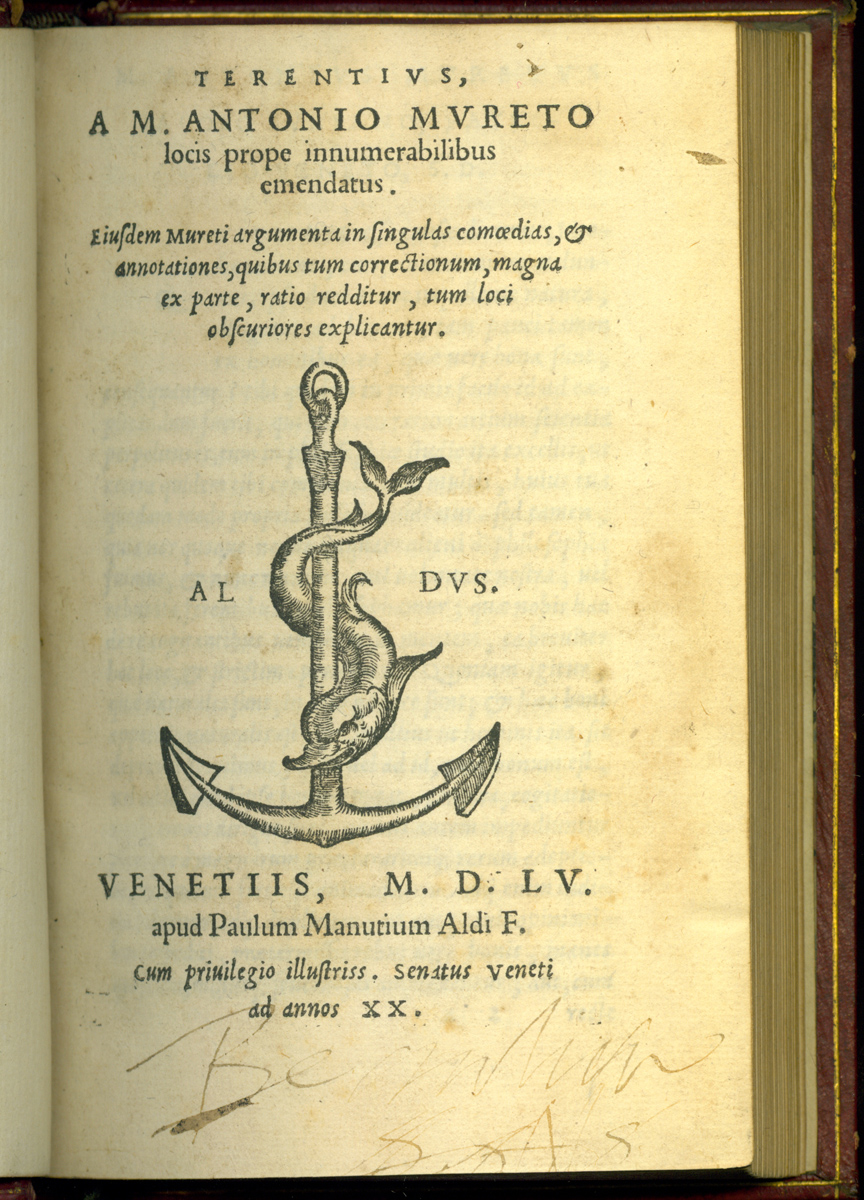

By mid-century, advances in philology meant that it was essential to proclaim on the title page that the volume contained a good text. The form could be elaborate or summary. A number of editions of the fifteen fifties, for example, carried routine boastfulness to a perfunctory extreme with titles that read, The Six Comedies of Publius Terentius Afer, lately corrected with the greatest diligence according to all the editions of all [six plays]. (61) The phrase was safely impossible to verify. At the other extreme were claims made for the text of Marc Antoine Muret. Muret and his publisher Paolo Manuzio portrayed themselves as vigilant correctors of the text. They let themselves in for criticism on this account because humanist scholars immediately replied with further corrections. The 1555 Muret text of Terence was particularly problematic in this way because it abandoned the older Aldine text, edited originally by Aldo the Elder and still much admired at mid-century. The Muret Terence even became a cause for debate at the papal court since both Muret and his principal critic, Gabriele Faerno, were clients of Pius IV. (62)

Other publishers who offered the Muret text, however, took up the theme of repeated correction as an advertisement and placed it prominently on their title pages. Gioacchino Brugnoli seems to have had this idea in mind when he took six lines on the title page of a 1582 edition to reclaim the quality of the text. Not only was the text corrected in almost innumerable places by Muret, something everyone knew had happened across many editions, but it was also furnished with Muret's notes giving the reasons for most of the corrections he made, and the book was carefully restored to the quality of Muret's original by the use of more than one corrected exemplar. Aldo Manuzio the Younger (1547-1597) adopted a similar advertisement on a 1588 title page, perhaps in an attempt to blunt criticism that the Aldine press had offered Muret's text in sloppy editions in the previous decade. (63)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (60) Baldachini 1994, 287 and 2004, 75-76; Godman 1998, 211.

- (61) E.g. Terence 1555a and 1558a.

- (62) Ceretti 1954, 523-556; Faerno called the older Aldine text a vulgata and insisted it was preferable in many ways to Muret's.

- (63) This wording derived ultimately from a Plantin edition, 1574b but apparently took this full form in the 1582 edition cited. It appears unaltered on other editions in Venice and Verona until at least 1606. Further on repeated correction as an advertisement, see sections 4.05 and 4.06 At least one grammatical author, Bernardino Donato in 1529, took exception to florid title-page rhetoric; he included a title-page note that tells the reader to look beyond the title page and scan the chapter headings in the book to find out what it really contains.