4.16 Toponomy

An alternative, equally literary form of Renaissance geography was the compilation of toponymics. The earliest humanists again provided a model, in this case a miscellany by Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375), On Mountains, Forests, Springs, Lakes, Rivers, Swamps and Seas, which he assembled from long and close reading of classical texts. The market for such compendia must have been considerable, for Boccaccio's book came into print in the early fourteen seventies and remained available, either as a separate or combined with his Genealogies of the Pagan Gods, throughout the sixteenth century. It got new life when it was translated into Italian about 1520 by Niccolò Liburnio (1474-1557). Although Boccaccio took pains to identify wherever he could the present locations and modern names for the ancient localities, it is clear that both he and his readers were most interested in clarifying not geographical realities but the literary import of the place names they would encounter in their reading. (68)

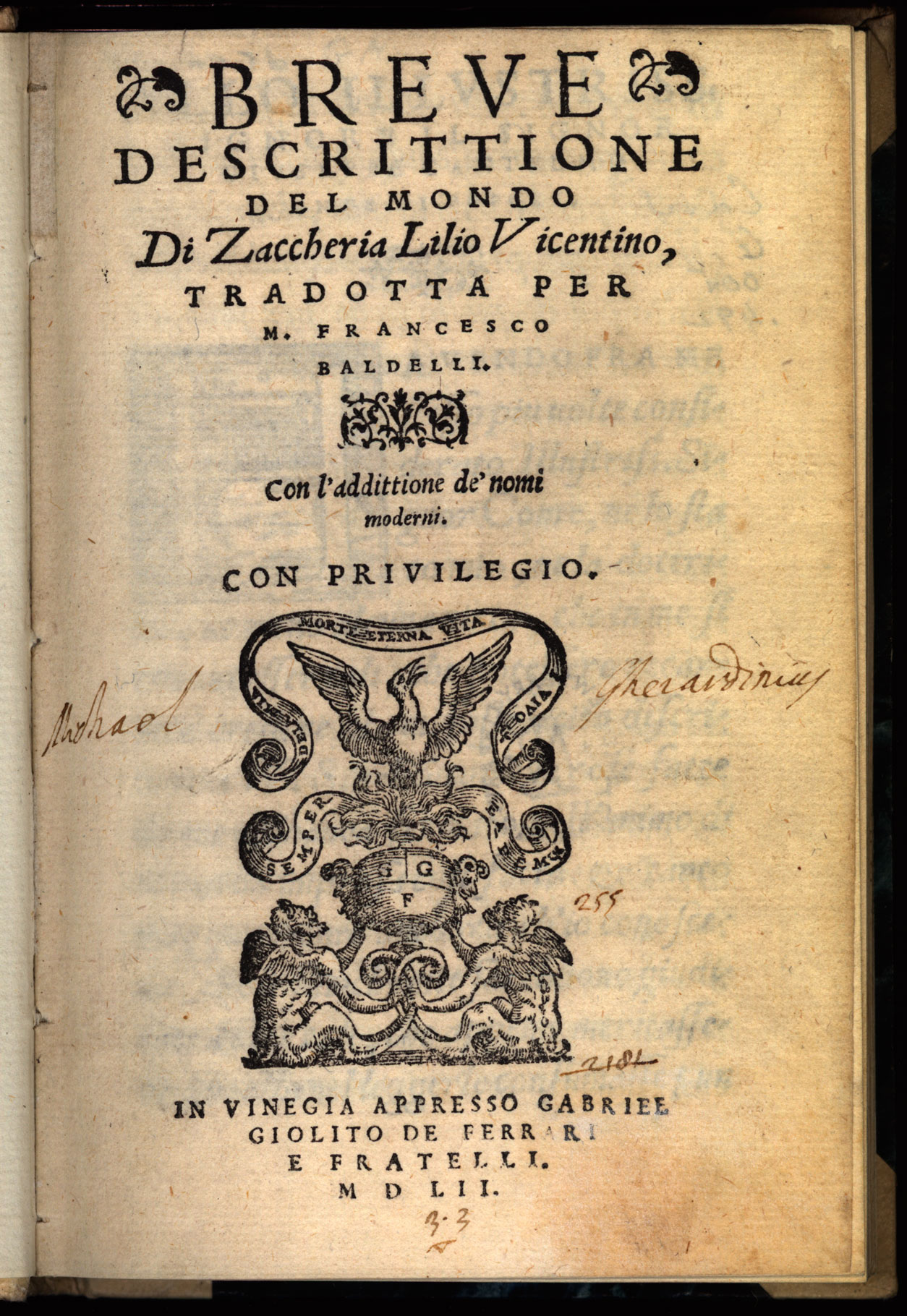

Another influential work in the toponymic genre was the Orbis breviarium of Zaccharia Lilio (1452-1522), which reduced much of the lore that interested Boccaccio to textbook form. (69) Its title (we may translate it Handbook of the Globe) promised a well ordered and easily memorized digest.

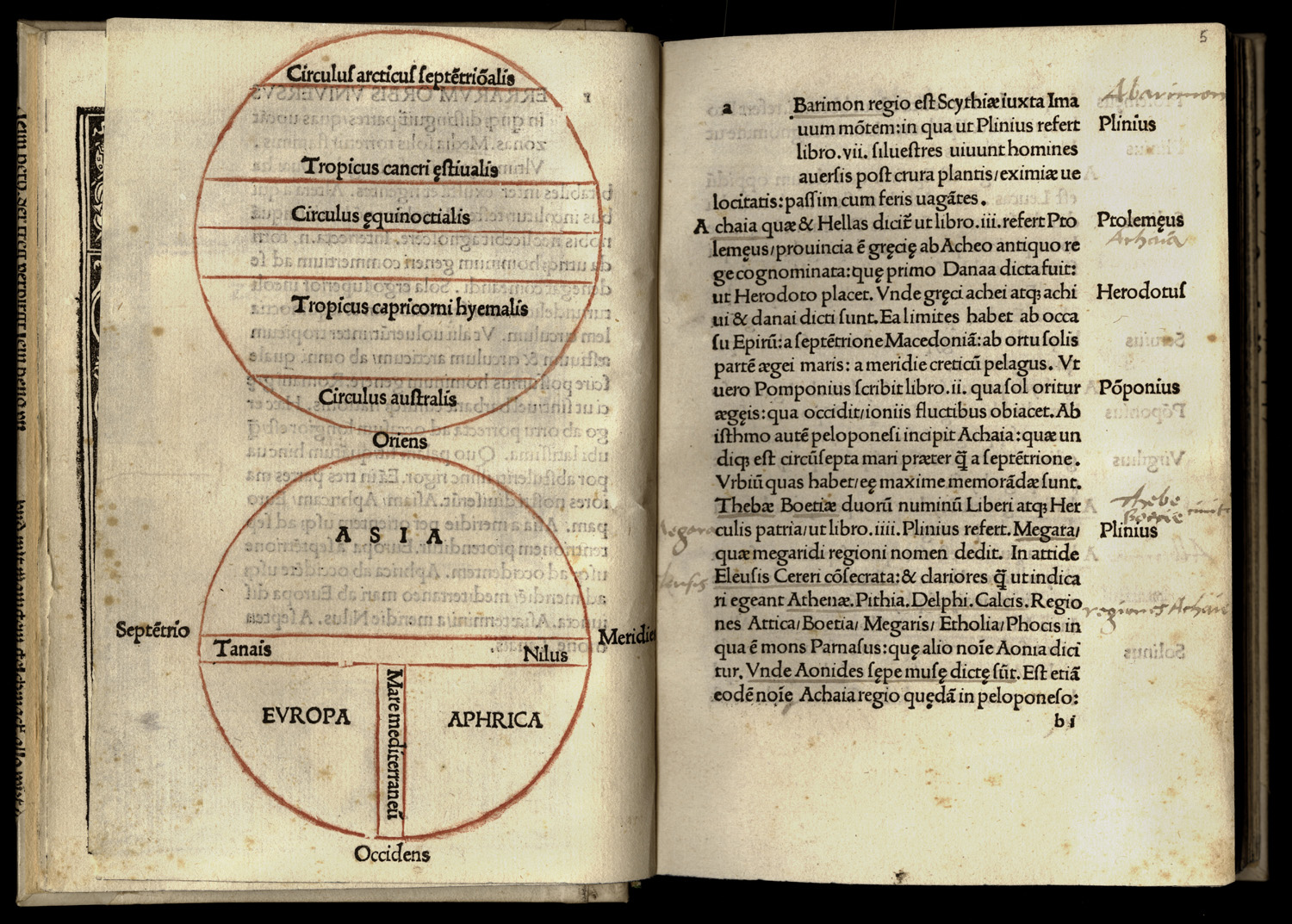

It opens with a brief, discursive discussion of the continents and the climate zones of the entire globe (rather the way Dati had opened his Sfera). But after this front matter the text quickly devolved into a dictionary of classical toponyms. The meaning of the book is stated in the letter of dedication, where Lilio claimed to have collected place names from Greek and Latin writers for the sake of advancing the eloquence of his readers, omitting only names that appear in travel writers whose authority was unclear. In particular, Lilio continued, he knew of many island books that contain newly discovered places not found in ancient writers, and their testimony must be treated with great care.

One early reader underlined a passage that emphasized the accomplishments of modern (philological, not geographical) scholarship, "In these cases authority belongs to those [writers] whom we have followed. For what can we moderns possibly claim as our own, since our ancestors failed to find anything that did not survive intact into our own day?" (70) This same reader underlined two other phrases: a remark, quoting Pliny the Elder, that not all the peoples of the world were known to the ancients; and another that the ancient names of places are unfamiliar or hard to understand because they have been corrupted by modern usage. The implication is clear. The ideal humanist needed a basic familiarity with geographical concepts and he had to understand the proper meanings of place names. He would perhaps also want to be aware of the new discoveries that were accomplishments of his own age; but he would naturally interest himself most in the classical literary tradition that conduced to eloquence.

Lilio published his work in Latin; an Italian translation appeared in 1551. Both versions were reprinted, attesting to the fact that this largely literary approach to geography continued to find an audience. Lilio's book was a genuine textbook, intended for study within the humanist curriculum; but the course in question was one in classical rhetoric, not geography as such. (71)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (68) Pastore Stocchi 1963; Bacchi della Lega 1875, 19-20.

- (69) On Lilio, Ravegnani 2005.

- (70) Lilio 1493, 1v, copy now at the Newberry Library: Cuius rei auctoritas penes illos est quos secuti sumus. Quid enim novi afferre possumus quod proprium nostrum esse possit: cum nichil maiores nostri omiserint, quod intactum ad hoc usque tempus permaneret?

- (71) Toponomy remained a popular literary and geographical form for centuries. However, Carlo Passi 1575 would complain that it was handicapped by the lack of comprehensive modern geographies.