7.04 Visualizing the Text

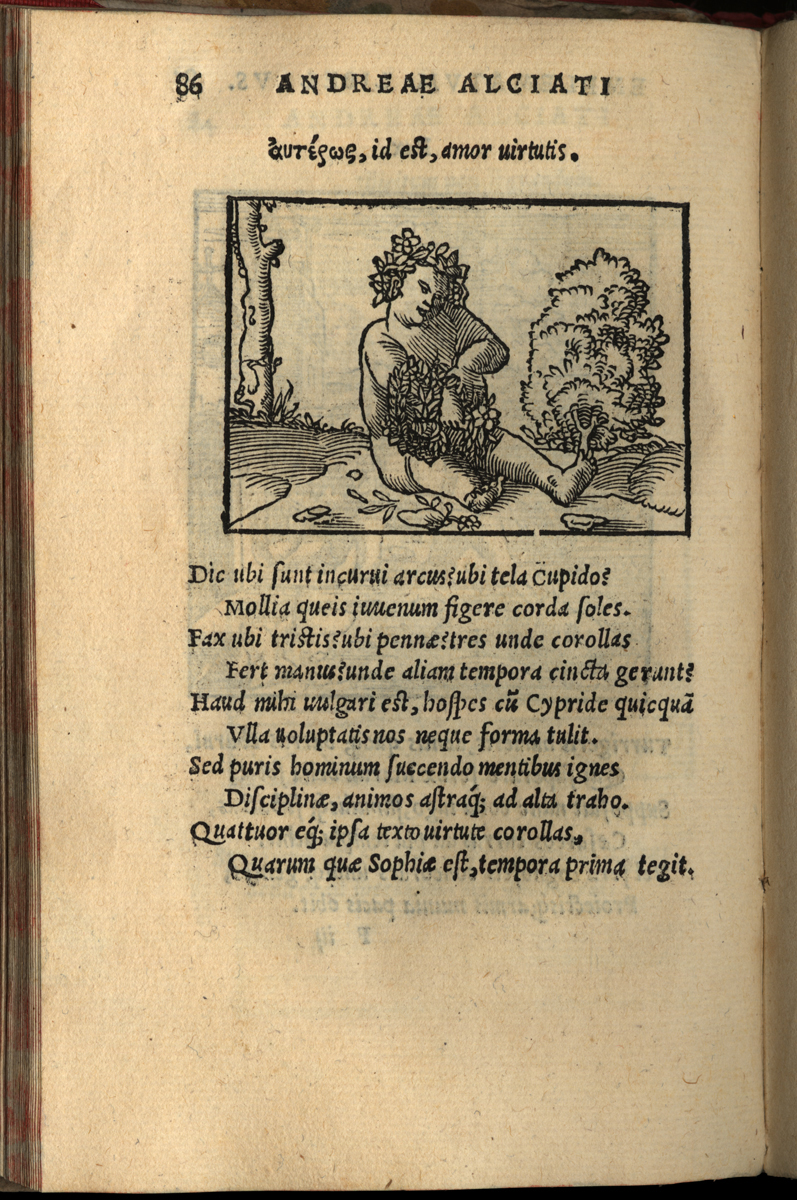

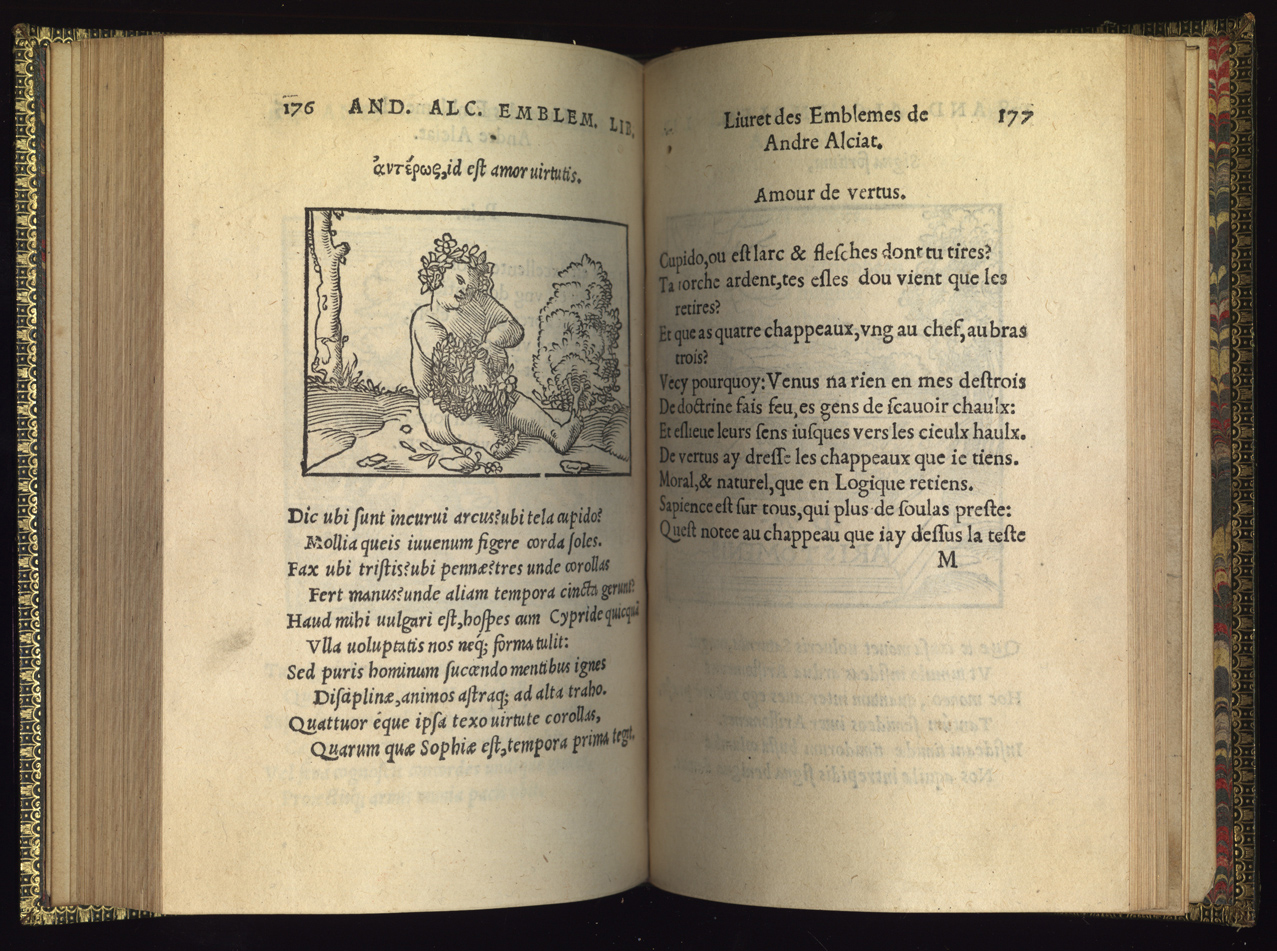

From the start, Alciati assumed active reader response in visualizing the images, but the process could be problematic. John Manning has related how Alciati's Emblem 110 proved difficult for artists; it appeared in the first printed collection of 1531 with a picture that is entirely inappropriate to the poem. The image is that of Amor, and the poem asks a series of questions, wondering where are the love god's bow, arrows, torch, and wings. It adds, why does he hold three garlands and wear another on his brow? As Manning notes, Alciati was inviting his reader to imagine a child or youth without any of the usual attributes of Cupid/Amor; but the earliest editions offered a standard-issue cupid with bow, arrows, and wings.

Apparently the highly standardized iconography interfered with a proper understanding of the verse, for the mysterious lack of attributes was made perfectly clear in the second half of the poem when the god himself replies that he is not promoting venereal love but love of virtue, that his laurel crown represents wisdom, and that he is weaving garlands of the other virtues. The motto also pointed in this direction, since it is "Love of virtue" (Amor virtutis). It took several editions prepared with advice from Alciati to fully correct the error.

Exactly the reverse iconographical drift occurred with Emblem 6, False Religion (Ficta religio). Early editions correctly showed an enthroned prostitute who offers the wine of delusion to her followers. Later in the century, the poem's passing reference to Babylon led artists to imagine the biblical whore of Babylon and show Alciati's strumpet seated on the seven-headed monster common in images of the Apocalypse. (9)

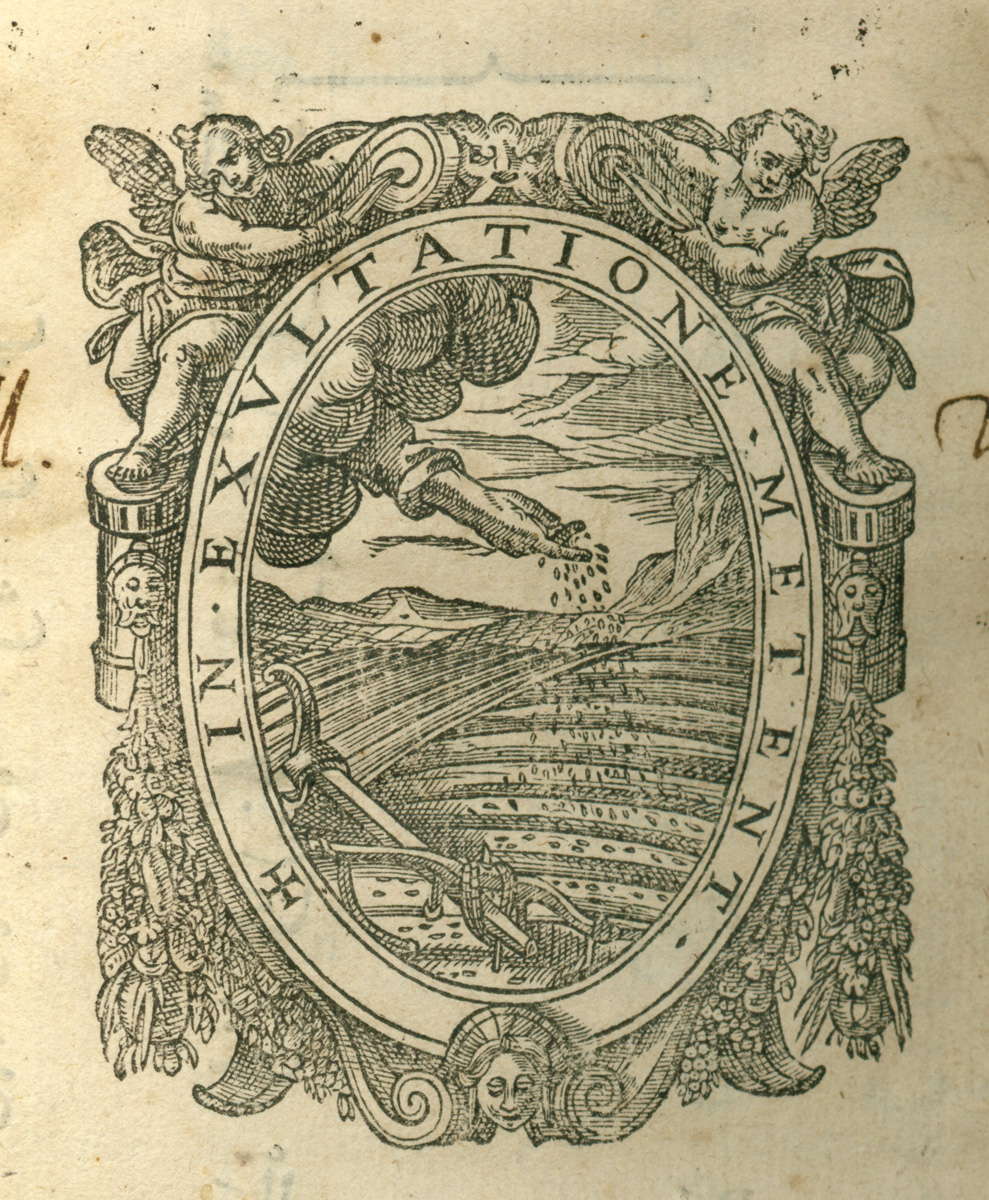

Alciati's emblems were generally straightforward and eschewed the kind of pretend mysteriousness that many emblem authors affected. Even straightforward emblems, however, were susceptible to multiple readings and indeed demanded them. In the emblem adopted as a trademark by the Medici Oriental Press, for example, the reader is presented with an image of a hand reaching out from a cloud and sowing grain onto a recently plowed field. The plow, apparently just abandoned by the plowman, sits atilt at the bottom of the frame. The accompanying Latin motto reads, "Rejoicing, they will gather the harvest." (10) In the then-current Italian fashion, and because this is a trademark as well as an emblem, there was no accompanying poem, so the relationship between motto and image was left to the viewer to figure out. The motto does not refer directly to the scene of plowing and sowing but to the far-off harvest. Since the Medici Oriental Press was a missionary effort devoted to presenting catechetical texts in oriental languages, the verbal/visual device here had a specific meaning with reference to Christian missionary efforts. But it was open-ended enough to be read more generally of the fruitfulness of hard work, something appropriate to any printing house and, indeed, to most areas of Christian life.

Almost all emblems are based on literary sources and imply a comparative reading of texts on related themes. (11) In this example, there was no exact verbal parallel for the motto about the harvest in either the Old or New Testament, but the author deliberately evoked scriptural language (that of the gospel parables in particular); and the saying easily suggested a whole range of moral readings. The emblem as a whole embodied more of the related biblical stories than either the single image of sowing or the motto about reaping could offer. So the reader was presented with two themes commonplace in themselves but slightly different from any in scripture, that labor is its own reward and that joy is a precondition for as well as the result of fruitful work.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (9) Manning 1989, 129-134; Manning 2002, 51-54, 277-279.

- (10) In exultatione metent. Tinto 1987, 44.

- (11) Manning 2002, 48-51.