6.19 Professionals or Amateurs?

The fifteen thirties and forties also saw the first Italian manuals for learning instrumental music. They multiplied rapidly. Typically books of the sort promised to teach their readers how to play "with all the artistry appropriate to this [or that] instrument." (100) The advertising on title pages and in prefaces to instrumental textbooks changed little over the next century. It did not matter much which instrument was in question, whether the book was really a beginners manual or a substantial, advanced one, or whether the contents were highly traditional or innovative. The lessons were always "brief and easy" and the process of learning "quick," while the book itself was always "most useful and necessary." (101)

Behind the title pages, however, the contents could vary considerably. Most instrumental instruction books included a brief discussion of theory, thorough examples of notation, substantial discussions of the use of the hands or lips in playing, and some advice on style. This material was followed by exercise pieces for practice, sometimes graded in difficulty.

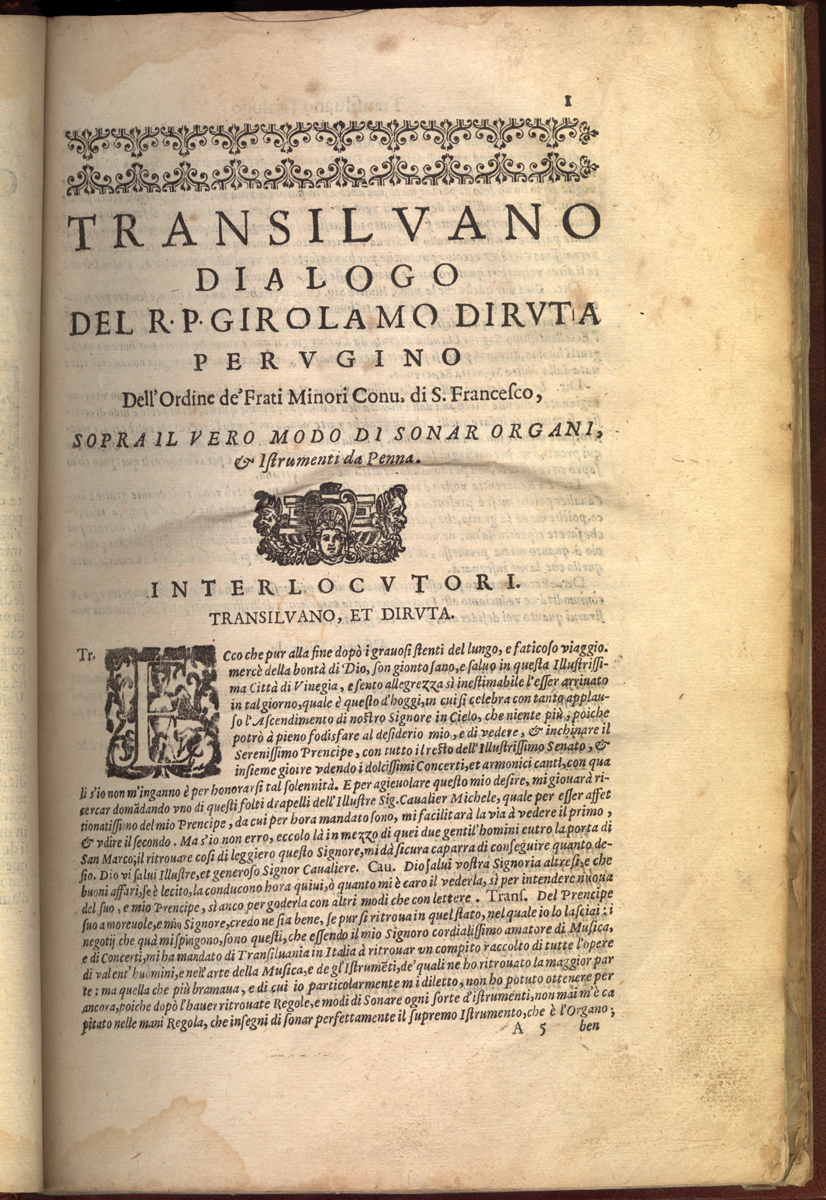

Some authors clearly intended their discussions for beginners or do-it-yourself learners, so they simplified the content and broke it into small sections. Other authors were addressing music teachers and dwelt at greater length on theory. And some, like Girolamo Diruta (1550 - ca. 1620) at the end of the century, clothed their work in an elaborate literary frame. Diruta constructed a lengthy dialogue between himself and a title character, The Transylvanian, who stood in for the dedicatee of the book, Prince Sigismund Báthory (1572-1613). The prince can only have been an amateur, but he is made to ask for detailed information from Diruta. The result is generally considered the most original and important Italian manual of keyboard practice. It was not intended for amateurs like Báthory nor for beginning students, but rather for organ teachers. (102)

The audience for a given music book is often hard to judge, though we can make some inferences based on content and formatting. Books that concerned instrumental practice often seem to have been aimed at amateur students or their teachers. Books on plainchant were clearly directed to professionals, though often performers of no great sophistication. Polyphony books almost always concern compositional norms as well as performance, and so we may assume that they were usually intended for professional musicians. (103) But the evidence for these conclusions is indirect or partial, except in the case of Lanfranco mentioned above (section 6.17). Only toward the end of the sixteenth century do we regularly find full-scale descriptions of the potential audience for music-instruction books in the vernacular.

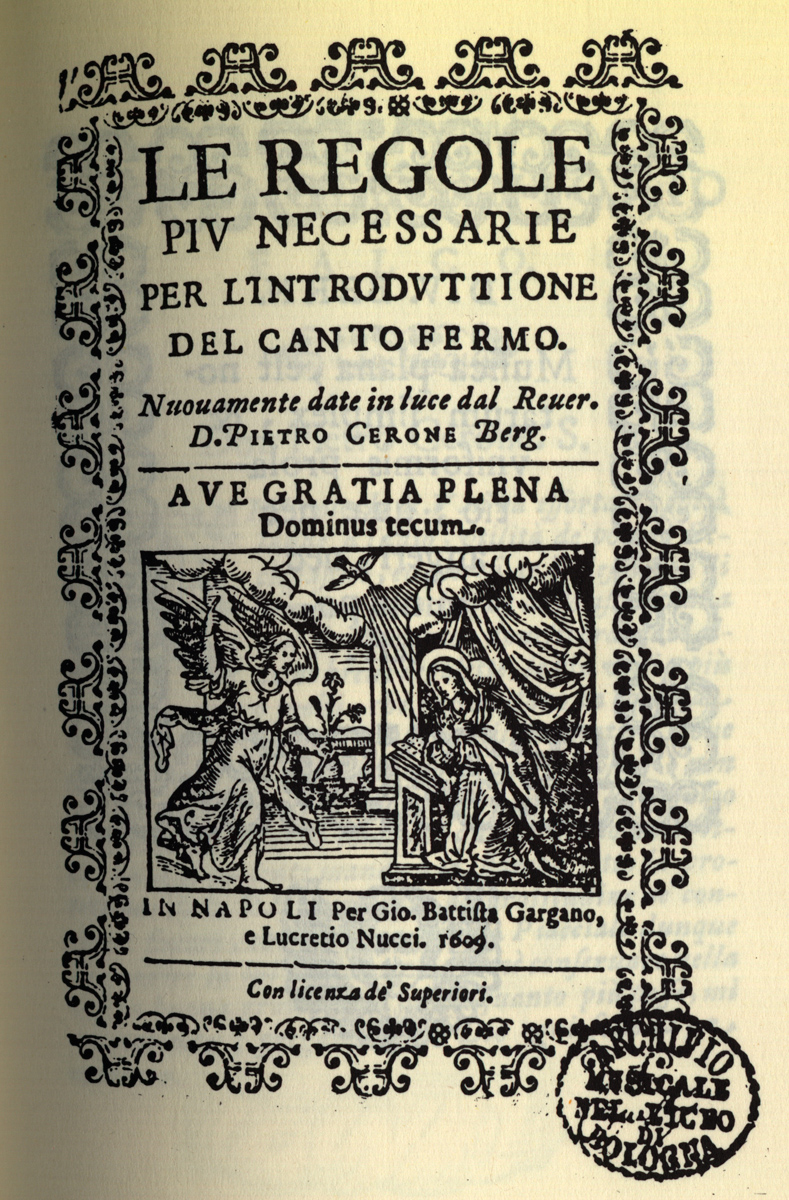

Pietro Cerone (1566-1625), a theorist and singing master at the church of the Santissima Annunziata in Naples, is typical of the new clarity. He published a short manual for student choristers in 1609. He labeled it clearly as a popularization, The Rules Most Necessary as an Introduction to Plainchant. His readers were beginners, or at any rate not highly skilled or well informed. His dedication described an audience exactly like that named by Bonaventura da Brescia in 1497, "poor churchfolk and others desirous of learning the basics of chant," but he elaborated on their poverty by saying that many choristers worked like blind men, to whom he hoped his booklet would bring light. (104) Cerone was even more explicit about the limitations of a song-school education in the afterward to his book, where he provided a long list of things he had not covered in his Regole. The list concluded, "and many other minor things too, which I think are not as necessary to a simple chorister as they are useful to the perfect choirmaster. What I have said thus far is great plenty for the service of the choir." (105)

-El-melopeo-y-maestro-tractado-de-musica-theorica-y-pratica,-3v-4r.jpg)

Cerone's forty-page Regole contrasts sharply with his larger manual, El Melopeo y maestro, which runs to no fewer than 1160 pages! This larger work appeared in 1613 in Spanish, a significant choice, for it must have been aimed in the first instance at the largely Spanish-speaking public of monks and nuns in aristocratic religious houses at Naples. Eventually it would be read widely in Spain and even in New Spain. (106) For such an audience, music was both a professional discipline and a cultural ornament worth studying in depth. It was also an integral part of a newly emerging international high culture. The new literature, art, and music were vernacular and international, but not univesalizing in the old Latinate sense. International use no longer depended exclusively on the old universal language, Latin, but could also be achieved multi-lingually, by employing sophisticated vernaculars with wide currency among cultured folk in many countries -- Tuscan Italian, Castillian Spanish, or the French of Paris. (107)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (100) Ganassi 1535: cho tutta l'arte opportuna a esso istrumento.

- (101) These epithets from Diruta 1609, part 2.

- (102) The first edition of part one dates from 1593, that of part 2 from 1609; see Diruta 1984; Gargiulo 2004, 173n.

- (103) Boorman 1986, 227-230; Owens 1996, 13-14.

- (104) Cerone 1609, 3: poveri Ecclesiastici ed altresi de là desiderosi di tenere i principij de la Musica piana. ... molti, che si essercitano in quella come ciechi, vengano ad essere illuminati. On Cerone, Sánchez Garcìa 2007, 67, 171-172.

- (105) Cerone 1609, 37: ... nè di molte altere cosette: per quanto mi pare no essere tanto necessario ad un semplice cantore, quanto utile ad un perfetto Chorista: che per servitio del Choro, lo detto fin qui, basta.

- (106) Gargiulo 2004, 180-182; Cerone1989, ix-xv.

- (107) For this ideal in chancery manuals, Trovato 1994, 71-74.