6.17 Poor Churchfolk

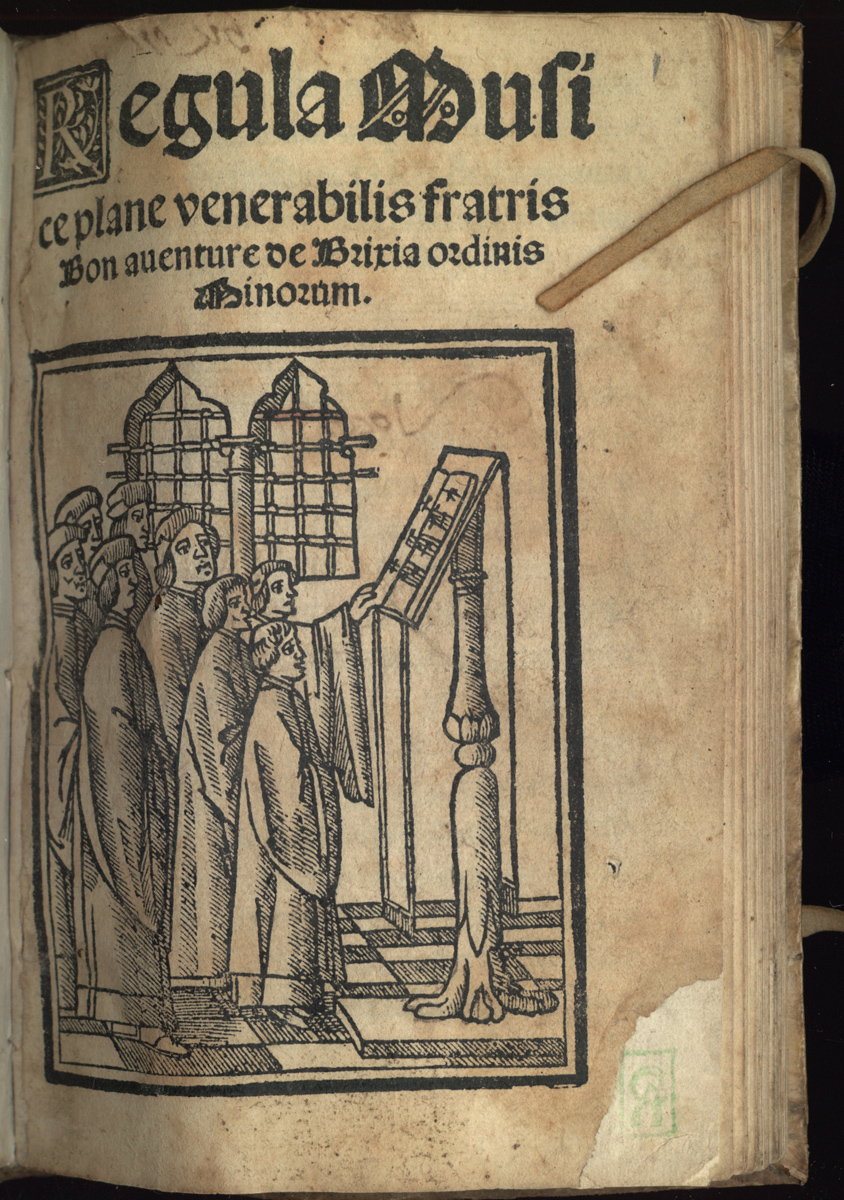

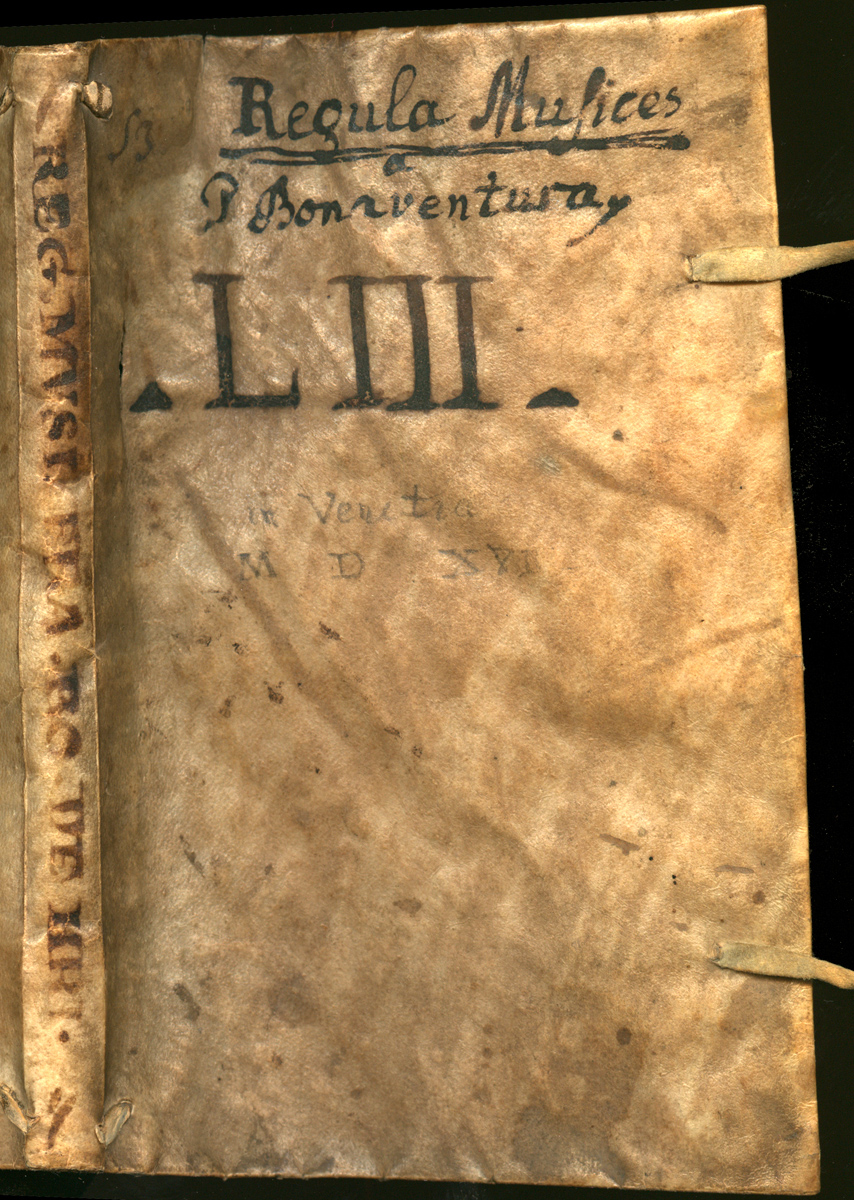

At the humblest level stood the Breviloquium Musicale (later titled Regula Musice) of Bonaventura da Brescia (late 15th century), one of the first known books to describe norms for performance without elaborate reference to music theory. It appeared in 1497 and had at least five Latin editions before 1540. It was reprinted in Italian in 1507 in a version that had over a dozen further printings up to 1550. (90)

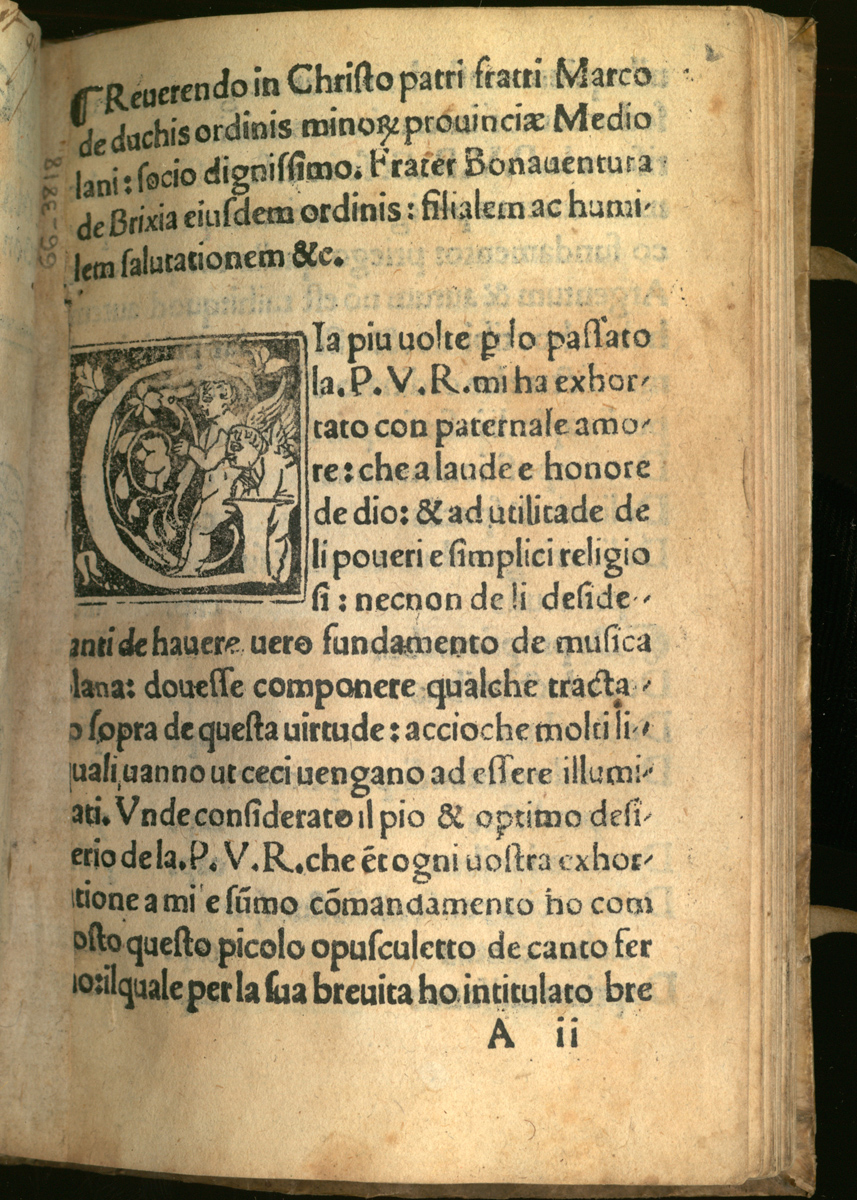

Physical examination of the two versions reveals that they were meant for different markets, even though both state the same ambition, to teach "poor and simple religious as well as others desirous of having the solid basics of plainchant." (91) The practical content is virtually identical in Latin or Italian, so the formatting choices were related to the marketing expectations of the printers.

The 1497 edition and most later Latin versions assumed the quarto format favored at the period for Latin-school textbooks, unpretentious but decorous and substantial. Italian editions could be in quarto but more often appeared in humbler octavo instead. An example printed in the smaller format in 1518 looks like other vernacular booklets we have seen (ricettari, for example) in that it begins with a popularizing title woodcut. It is otherwise modest in the extreme, thirty-one leaves roughly printed.

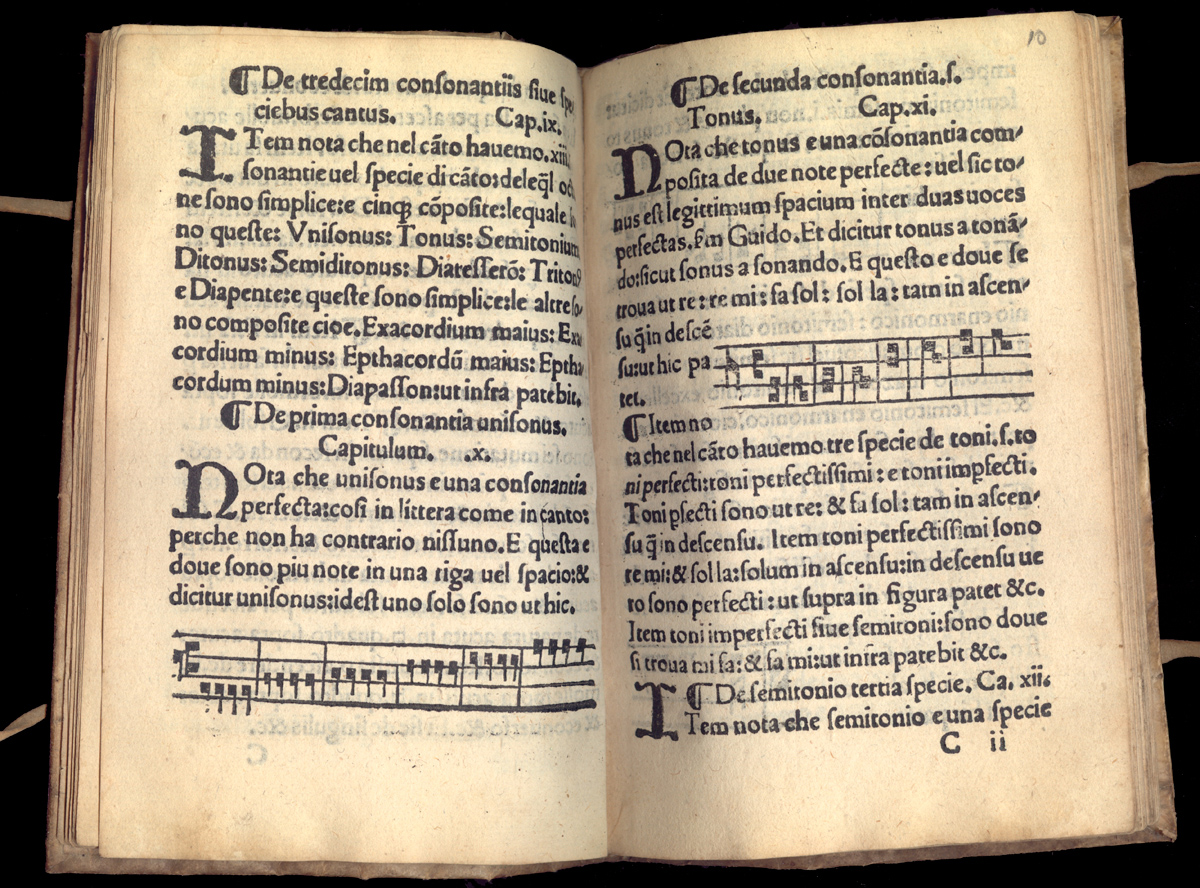

It differs in look from a simple ricettario only in having woodcut musical examples on almost every page. These cuts did not represent additional cost to the printer since they were simply blocks reused from an earlier Latin edition. Like the blocks, the text was a recycled product intended to make the original more widely available both by translating it into Italian and by cheapening the book in terms of paper, type, and format.

The epithet poveri religiosi was to some degree conventional even in these first years of printing music manuals, but the fact that the book came out first in a modest Latin version and then in downright cheap Italian ones suggests that many members of the target audience would not or could not spend very much on a textbook. (92)

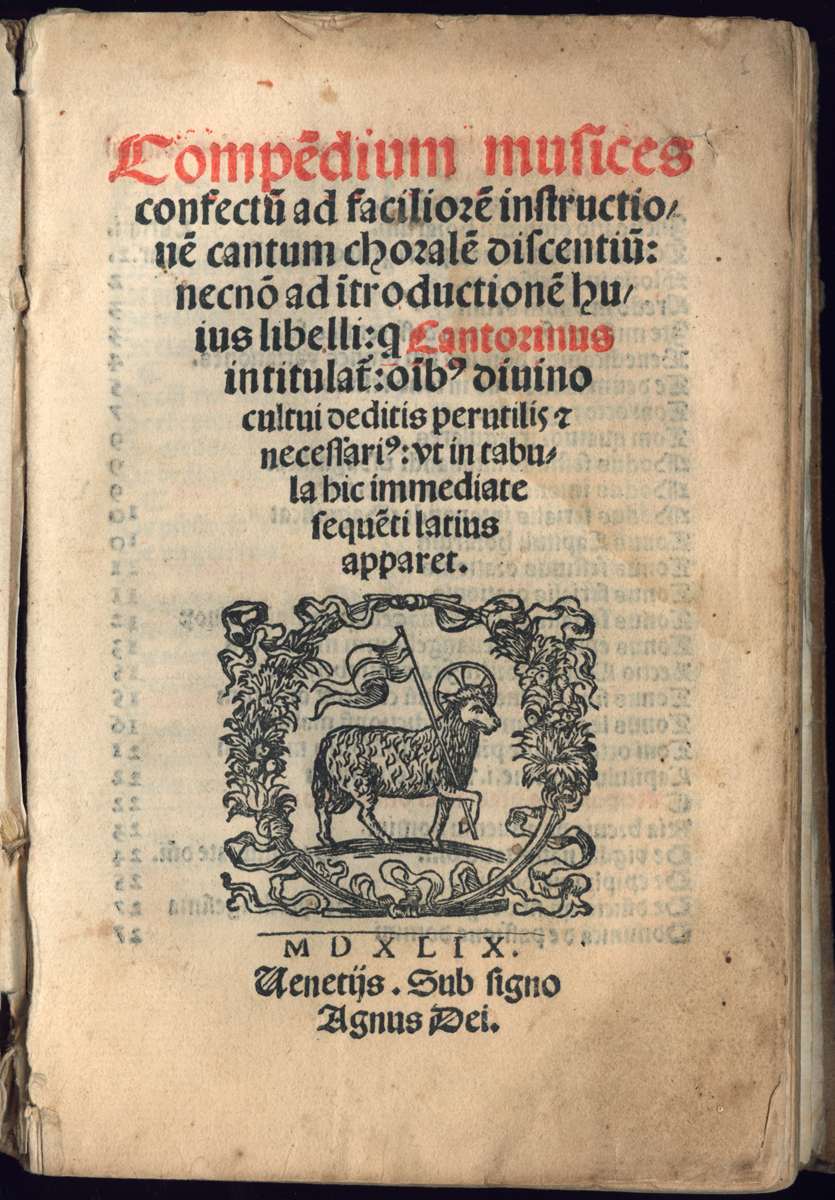

The principal rival to Bonaventura's Breviloquium on the Italian market at the turn of the sixteenth century was an anonymously compiled Compendium musices that received several editions between 1499 and 1509. It is less well organized than the Breviloquium, merely a series of observations on basic music theory that might be useful to singers. It may have been intended more for choirmasters than for simple choristers, a supposition confirmed by its subsequent history. After 1509 it appeared in print more than twenty five times, but only as a preface to other, more extensive handbooks for liturgists.

From 1513 to 1566 it was often printed in combination with the Cantorinus, a small, cheaply printed collection of specimen chants (primarily initial and final phrases) for use on various feast days throughout the year. From 1523 onward, the Compendium was also included in the Rituale, a large reference book of prayers and chants. (93) Both the Compendium musices and the Breviloquium of Bonaventura were practical texts for clerics who sang professionally. Neither had any pretensions to teach music theory as a cultural ornament.

A similar audience, though perhaps one more open to humanist ideals, was intended for the Sparks of Music by Giovanni Maria Lanfranco (ca. 1490-1545), published at Brescia in 1533. This work does not seem to have been influential; but it was a real textbook for singers -- simple, step-by-step instructions with good examples for practice. Lanfranco dressed his book with elaborate front matter that claimed a classical pedigree for his teachings, but the remaining one hundred forty four pages are strictly matter of fact. Tellingly, he deliberately wrote not in Latin or literary Tuscan, but in "the universal Italian speech" (an all-purpose North-Italian amalgam), "in order not to offend the ears of most with some words spoken in too Tuscan a fashion." More self-consciously than any earlier music writer, Lanfranco identified his audience as beginners. (94)

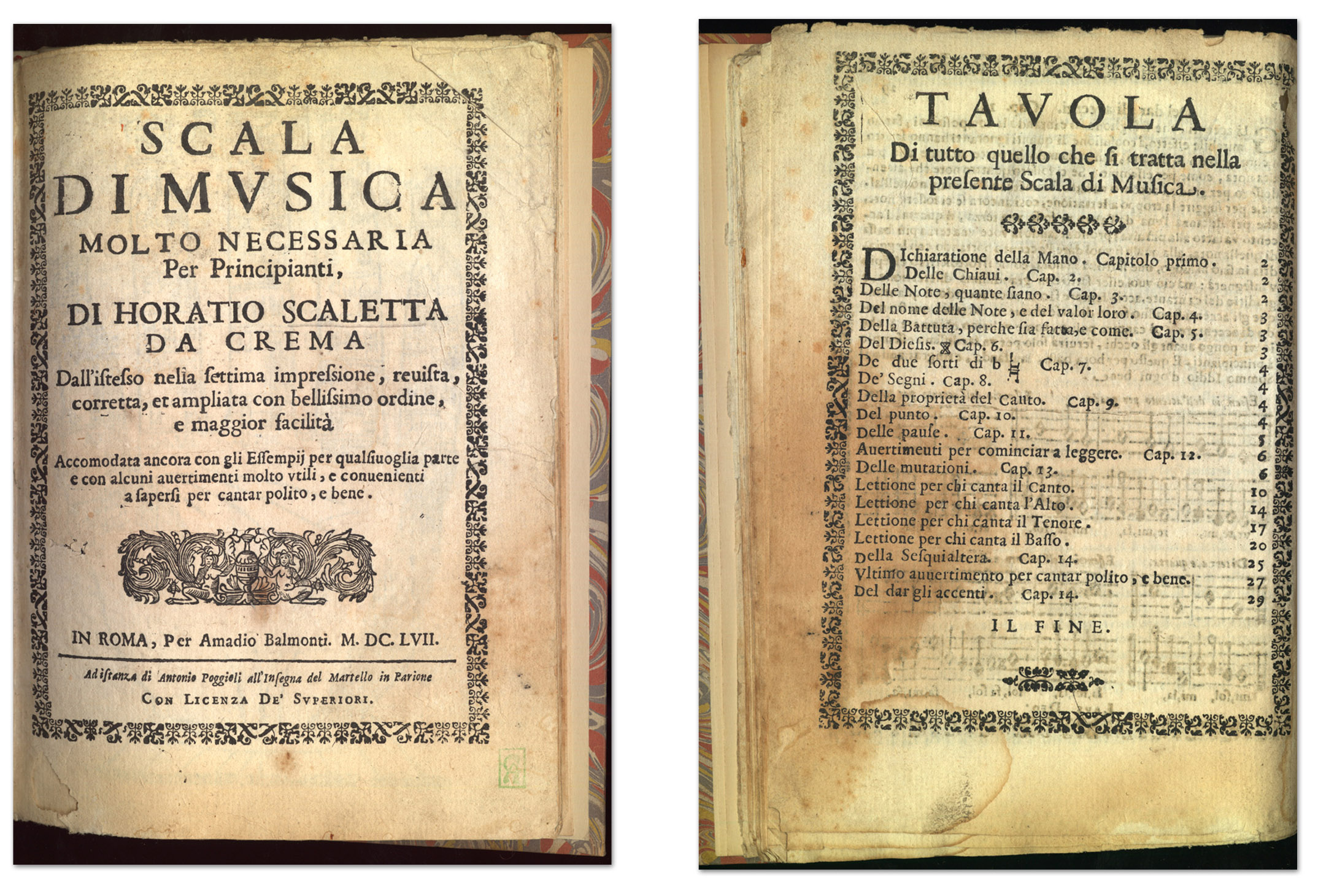

There continued to be a market for small, rudimentary manuals of plainchant right into the seventeenth century, guaranteed by the large number of churches and monasteries with choirs to train. The physical form of such books changed little, so that the first editions of the Compendium musices (1499) look much like copies of the Ladder of Music (Scala di musica) of Orlando Scaletta (1650-1630) published until 1665. Even a fashionable composer like Adriano Banchieri (d. 1634) published four small booklets for teaching plainchant in the traditional, downscale format between 1601 and 1623. (95)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (90) Crawford 1982, 176.

- (91) Bonaventura 1518, fol. 1v: poveri e simplici religiosi necnon de li desiderosi de havere vero fondamento de musica plana.

- (92) On the commonplace of the poor and simple reader, West 2006, 257-260.

- (93) Crawford 1982, 176-187; Compendium 1985, 15-26.

- (94) Lanfranco 1533, 39; Lanfranco 1970, ii; Lee 1961, 60; see also 11-20, 52-63.

- (95) On Banchieri's manuals, Cranna 1981, 14-15. The Scala di musica of Scaletta, concerning plainchant, appeared in at least eight editions between 1622 and 1665; he also published a Primo scalino on counterpoint in the same booklet format.