6.11 Vernacular Literacy

The birth of the reading-instruction textbook in Italian can be just as precisely dated as the equivalent handwriting texts. Classroom materials for teaching the alphabet and syllabary existed in the late Middle Ages (in manuscript, of course); and they are evidenced in print in the early sixteenth century. The rare surviving examples are so similar in content and presentation that we must assume a fairly standard course of study that had been in place for some time. The abaco course was similarly standardized, and Piero Lucchi argues convincingly that the regular form of these most elementary language-teaching aids derived from a reading course that abaco masters had devised for those of their students who did not attend the pre-Latin reading schools. (65)

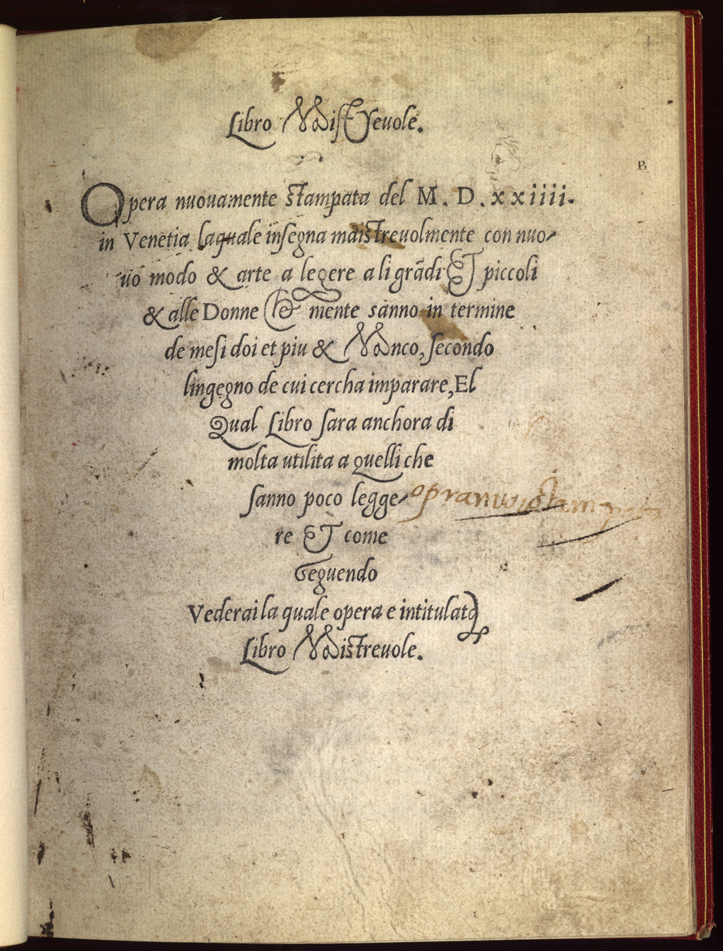

Outside Latin and abaco schools, the catechism would become the most common elementary reading book for early-modern children. (66) But there were no catechisms in Italian before 1530. The first full-blown vernacular reading textbook in Italy, then, was almost surely the strikingly non-religious Libro maistrevole of Giovanni Antonio Tagliente, dated 1524. Tagliente reveals a great deal about the facts of his invention. Indeed he spent five pages of his twenty-page booklet on an apology for it. We learn that Tagliente had taught reading as well as writing for many years, and that his son Paolo helped in bringing the project for a reading book into print. The elder Tagliente further implied that his decision to publish the work derived from the sense of duty he acquired as a servant of the Venetian state, even that he was charged (as an appointed teacher in the state schools) to find better methods of teaching non-Latin students. At Venice, state schooling for scribes was limited to a few students at a time. Tagliente claimed that the need for reading was so widespread in urban society that self-help books like his were called for. Anne Schutte points out that he saw this as a secular, specifically non-religious need in Venice, the commercial capital of the Mediterranean. Tagliente was not anti-clerical or irreligious, but religious education was not his brief. He carefully excluded devotional material from his textbook. It is less certain that he accurately understood the potential audience, since the Libro maistrevole, unlike other textbooks he authored, was apparently never reprinted. Later reading-book authors deliberately included the prayers and pious texts that were traditional for teaching reading to small children from the Middle Ages forward, exactly the sort of thing Tagliente left out. (67)

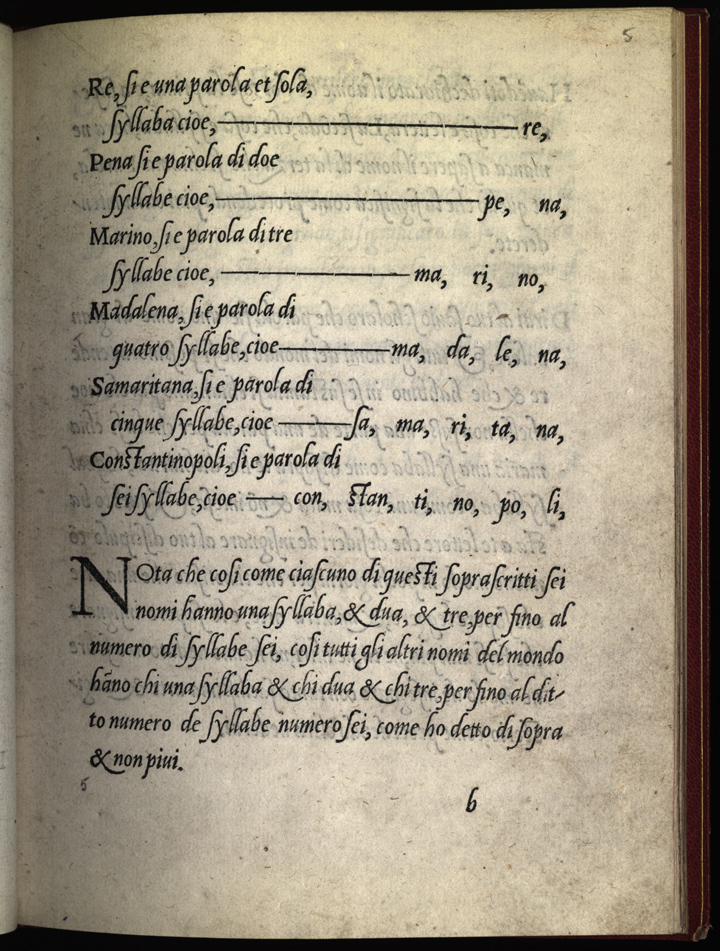

Throughout his reading book, Tagliente modeled the teacher-student relationship in a double way -- both on that of parent and child and also on that of a literate friend for an illiterate one. At various times he called his students bono, sollicito, prudente, valente and the like, repeating the kind of encouraging compliment an affectionate teacher should constantly give the student. As Schutte notes, these claims do not seem to be mere advertising; they almost surely represent Tagliente's classroom practice of many decades. (68) Other telling bits of the Libro maistrevole must derive from Tagliente's classroom too, as when he explained the meaning of "syllable" by inviting the student to imagine a man on his sick bed who can only call out for the maidservant by gasping her name syllable by syllable, "Ma-da-le-na!" On the other hand, the fact that Tagliente's reading book appeared in the same year as his handwriting manual (and close in time to his arithmetic books) suggests that all these new books were aimed at a how-to market that Tagliente had only recently identified, and not at his students of many years.

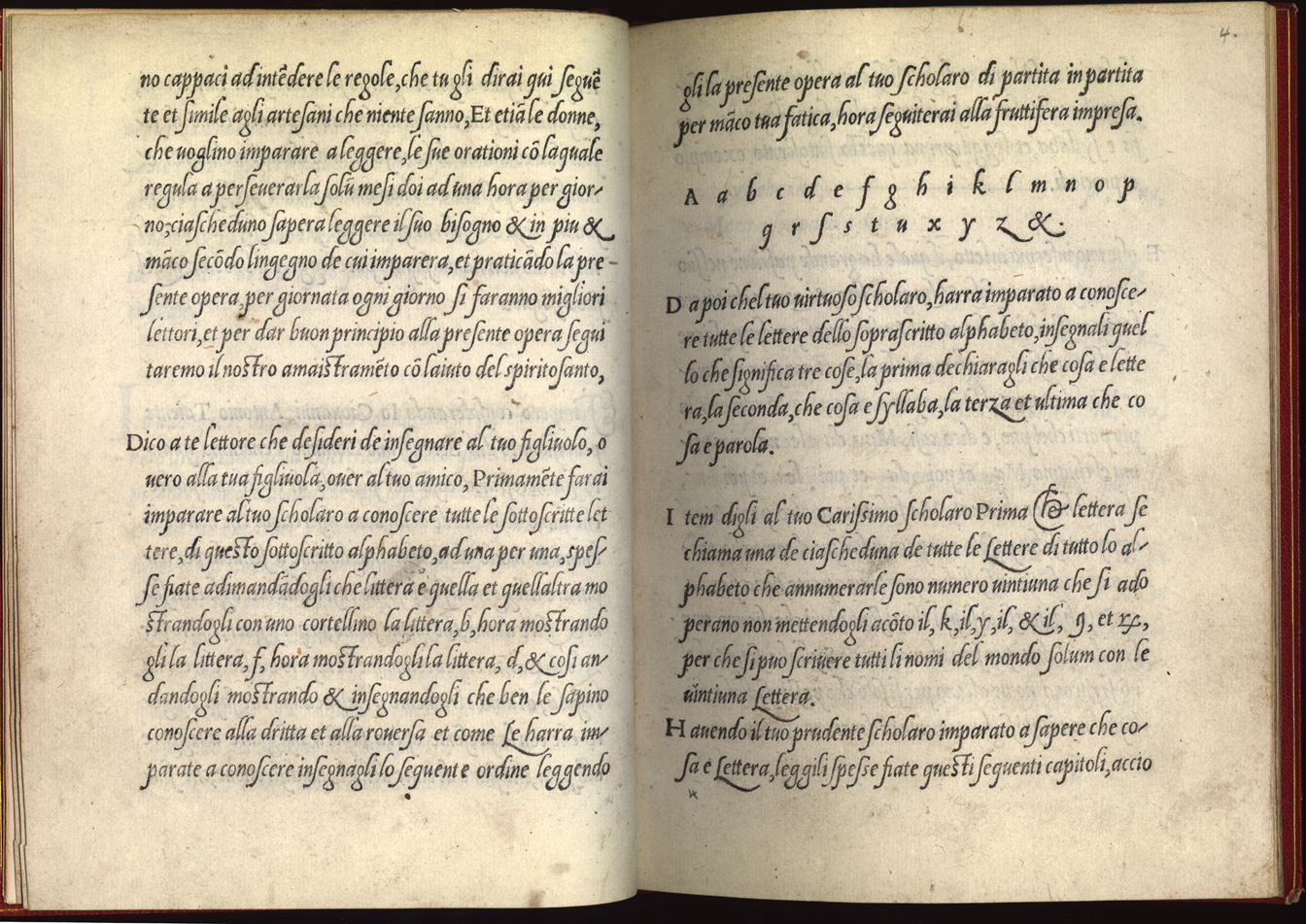

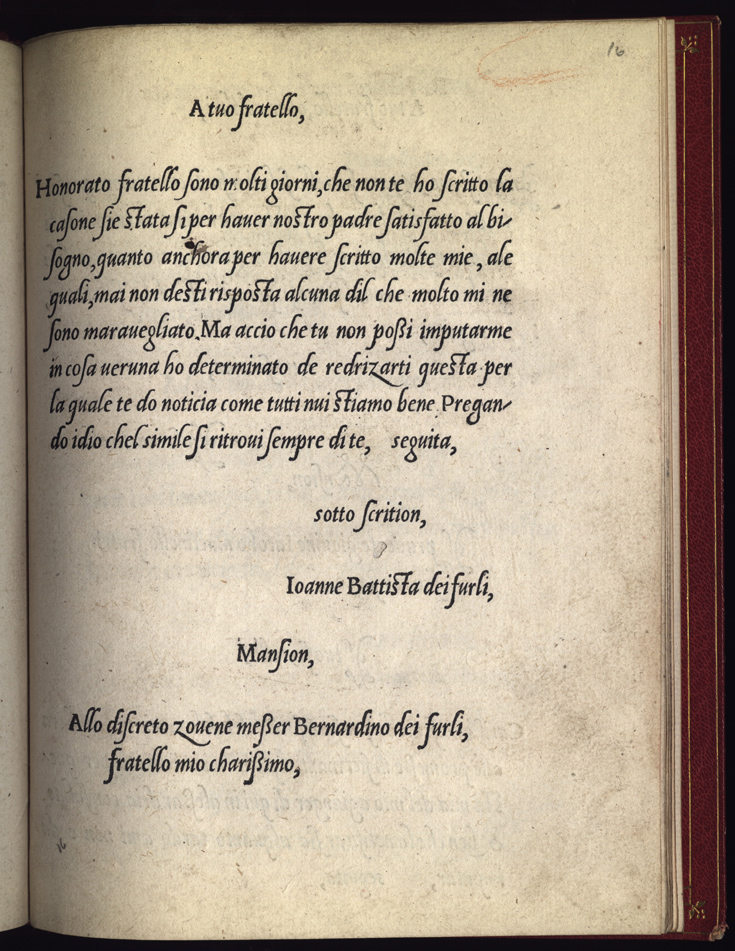

Although Tagliente explicitly disparaged the long and complicated course of Latin reading skills sanctioned by tradition, his own book proceeded in much the same order. The student must recognize letters, then syllables, then words made up of syllables. Tagliente stripped the process down to its barest essentials and concretized the lessons with examples of the kind of written Italian the student was actually likely to encounter: personal names, common account book phrases, friendly and business letters. Then, returning briefly to a commonplace of traditional Latinate pedagogy, he added a few moral proverbs.

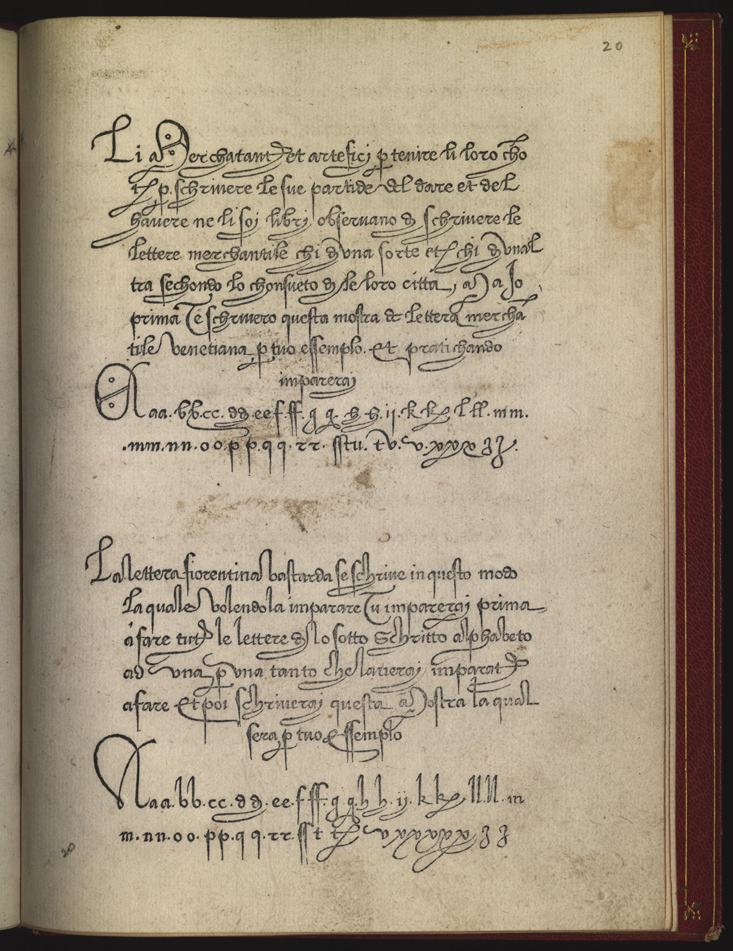

Anne Schutte believes that the sample letters, the moral proverbs, and some specimens of merchant hand (mercantesca) at the close of the Libro maistrevole were miscellaneous and casual additions to fill out the pamphlet. Matter of this sort seems more appropriate to a writing manual or a composition course than to beginning readers. (69) But it is just as likely that the thoughtful Tagliente set out to give his neophyte readers some additional reading samples for practice. The letters and the otherwise unrelated mercantesca specimens were good practice in real-life reading, while the proverbs reinforced the kind of moral thought that parents and teachers of the period universally recommended, even when, as Tagliente did, they chose not to emphasize Christian themes. Tagliente's contemporary Marin Sanudo (1466-1535) expressed this sense of a good literary education when he described Venetians students wishing "to acquire virtue and become learned" and called state-school teachers like Tagliente men "who teach virtue and grammar to the young patricians and others." (70)

The Libro maistrevole is very handsome. Less fussily prettified than most how-to books that preceded or followed it, its design rests upon a beautiful italic type of Tagliente's own design. The typeface has numerous outsize ligatures to imitate chancery hand; and the body of the type is very large, so the space between lines is unusually generous for so small a booklet. The spacing has a pedagogical intent too, as we can deduce from Tagliente's advice to the teacher to use a knife or pointer to indicate the letters and syllables that the student is to read aloud. Tagliente's professionalism as writing master shows through in every line of type. His layouts offered the inexpert new readers a page that is both charming and highly legible. Though the format is not large, it is easy to imagine that the book could be used by two people at once, the struggling student and an affectionate parent or friend.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (65) Lucchi 1992, 150-51.

- (66) Houston 2002, 62-65.

- (67) Schutte 1986, esp. 14-15. Tagliente and Arrighi also largely excluded religious texts from their handwriting manuals of the fifteen twenties. This practice reflects their target audience of secular scribes in training. Tagliente did use an occasional religious text to display black letter forms of the sort used in liturgical manuscripts.

- (68) Schutte 1986, 8. On the family as a locus for literacy learning, Bartoli-Langeli 1991, esp. 76-78.

- (69) Schutte 1986, 15-16.

- (70) Cronichetta, quoted by Ross 1976, 557.