6.10 Down-Market Handwriting Books

Like commercial arithmetic books, many handwriting manuals were intermediate in intent from the start. Their authors recognized that the rudiments had to be acquired with a teacher's personal guidance and that a textbook could never be much more than a series of additional, increasingly complex exercises for the student to follow. Books of this sort skip such elementary matters as cutting the pen and positioning the hand and body. Instead they offer a series of models, more or less miscellaneous, to students who have already well begun. Most of the great masters of the sixteenth century produced model books on this intermediate or showpiece level in addition to their more comprehensive manuals and, as we have seen, some may even have been producing them as souvenir booklets aimed at a market of upscale travelers.

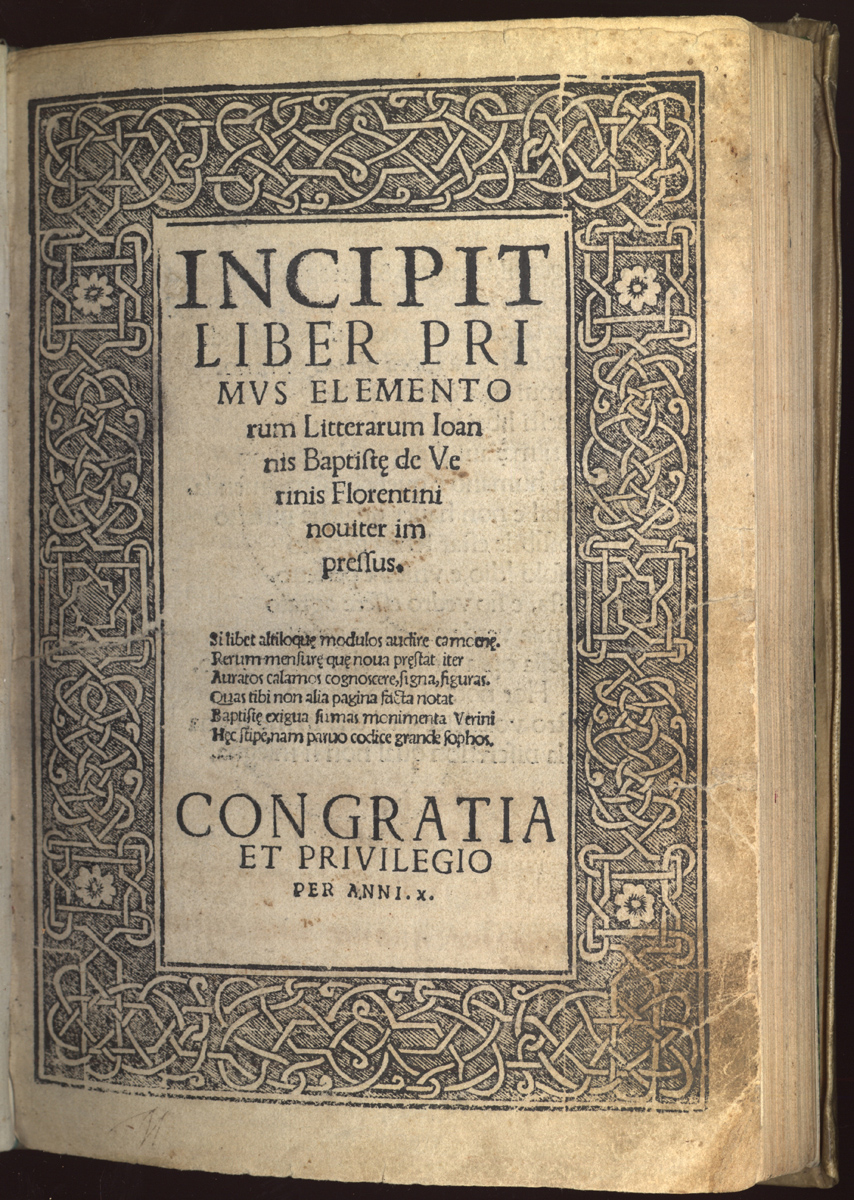

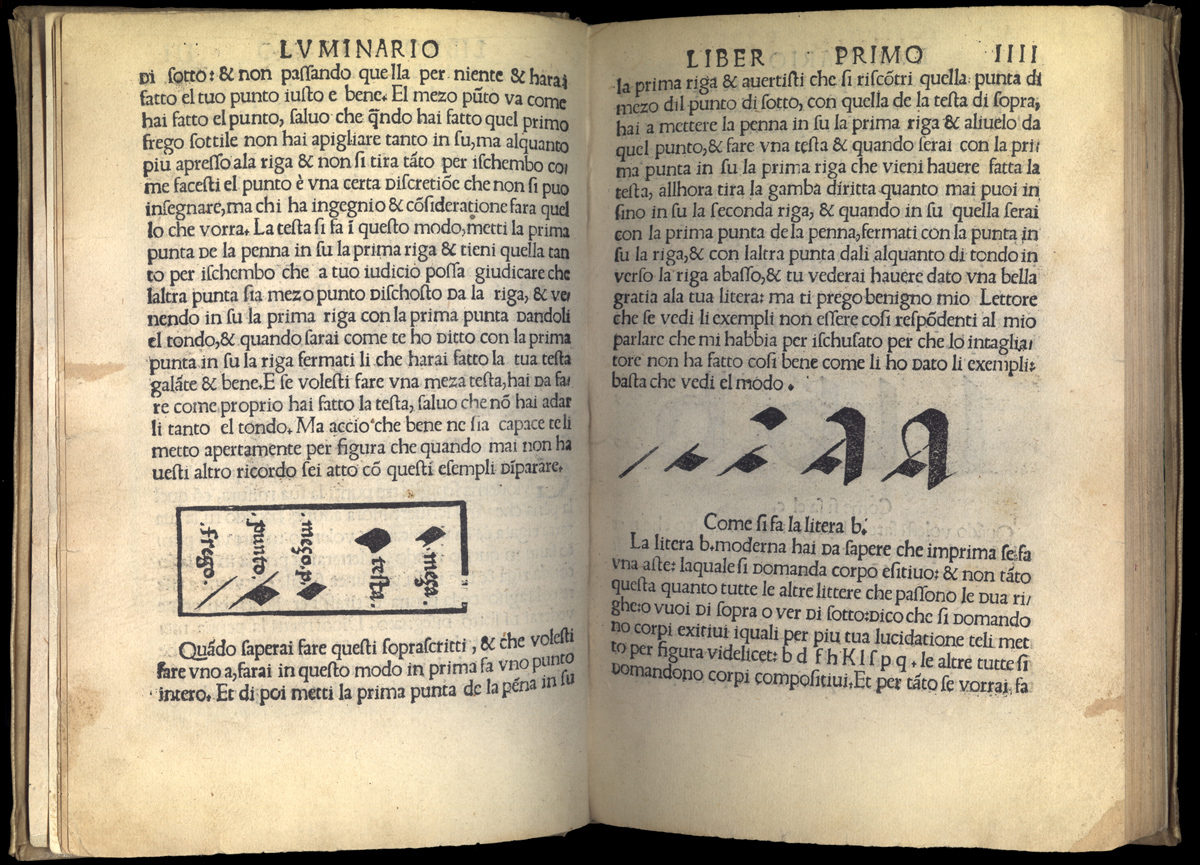

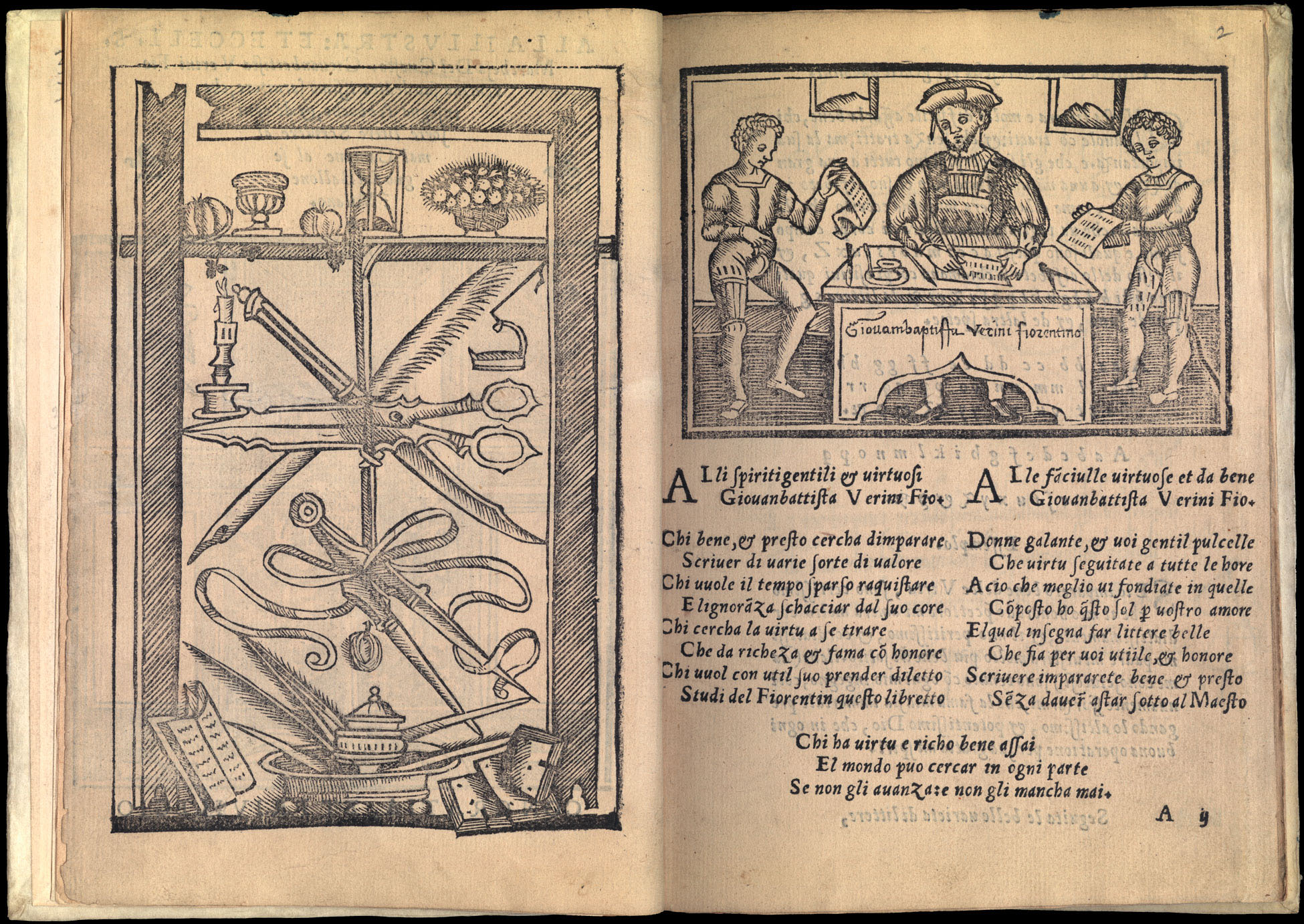

Apparently, however, there was local demand for much humbler books of this intermediate sort too. Among the few that survive are the works of a Florentine writing master, who styled himself Giovambaptista Verini. The market for Verini's books probably consisted largely of his own students at Florence, Venice, and Milan. In 1526-27, clearly imitating the success of Tagliente and Arrighi, Verini issued a rather elaborate series of models in four books (each with a separate title page, although they are foliated continuously in print). On the first title page Verini or his printer called this manual Chapters on the Fundamentals of Letterforms (Elementorum Literarum Libri), a high-sounding Latin title. The preface and running heads indicate that Verini also called his book Showcase (Luminario), accurate enough a label since the book really does consist almost entirely of illustrations of the practice of lettering. As such it is highly miscellaneous.

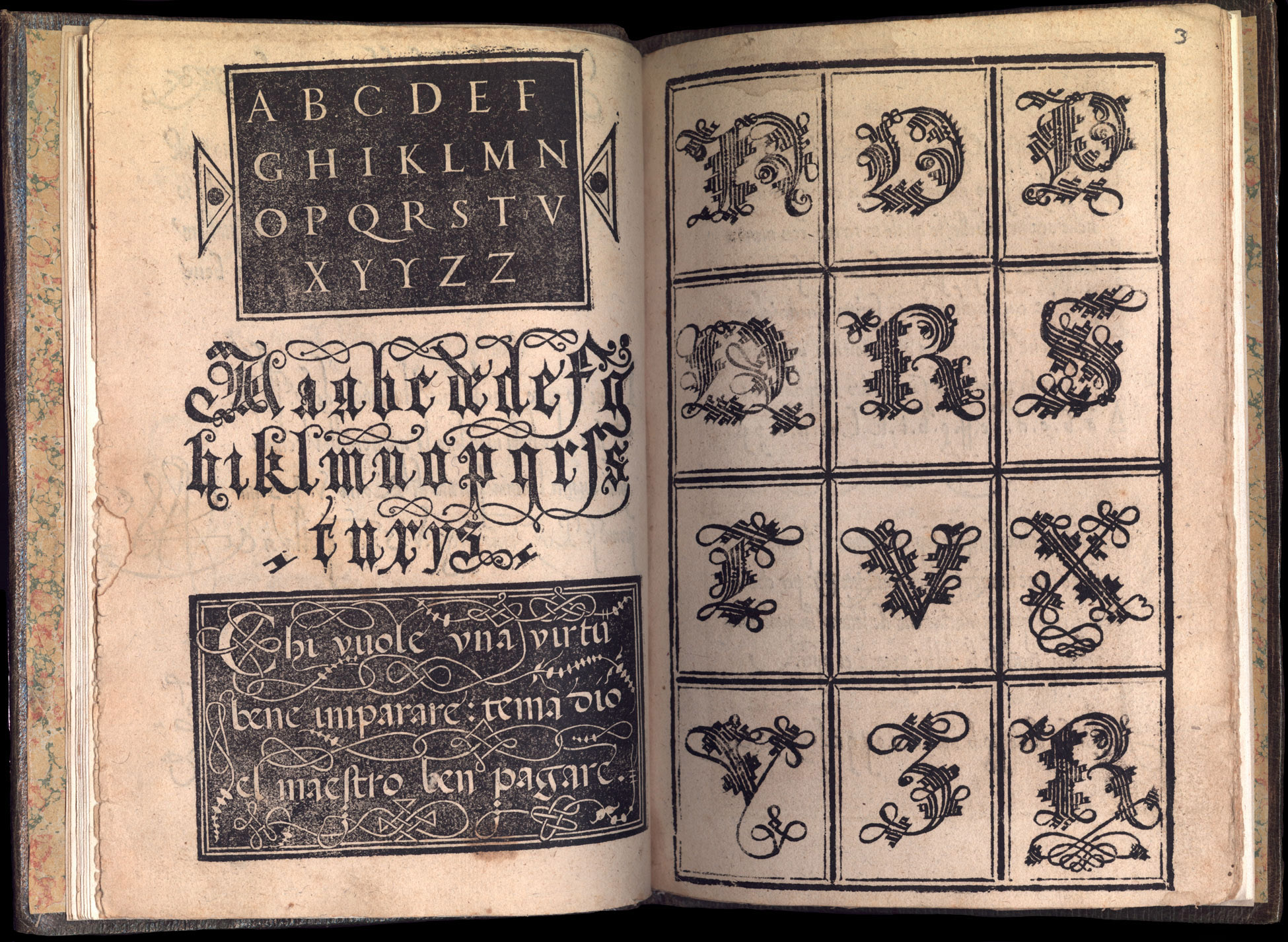

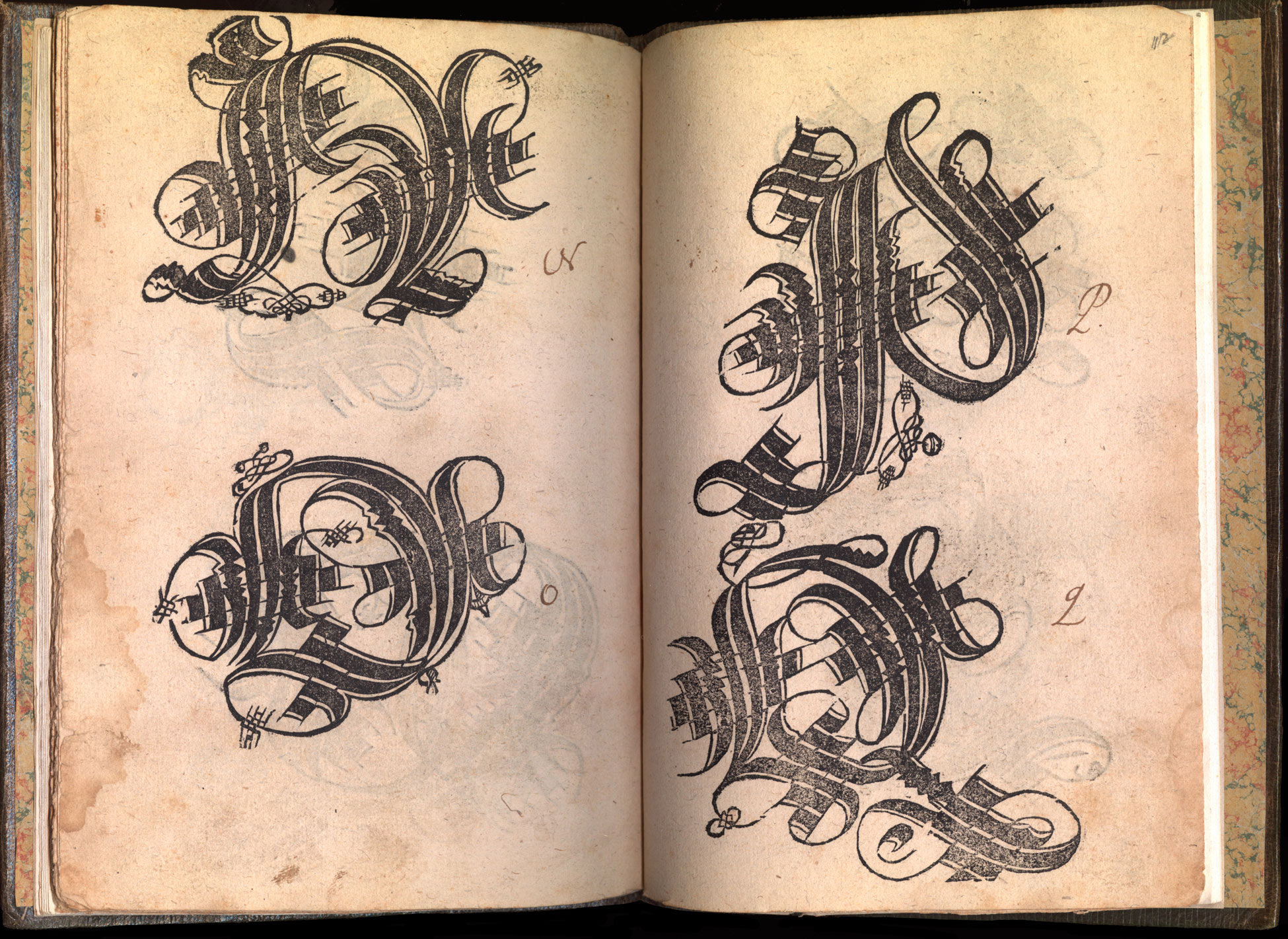

Book One gives detailed instructions for the pen work of a gothic hand described stroke by stroke. Book Two gives geometrical constructions for this same letter form. Book Three is a constructed roman alphabet on models like those Sigismondo Fanti and Luca Pacioli (the mathematician) had published earlier in the century. Book Four is highly miscellaneous. It is arranged around a large, beautiful alphabet of initials in Flemish interlace style, but the rest of the contents do not much hang together. (57)

Verini went on to issue a whole series of other, more modest booklets on writing, first at Venice and later in Milan. As time went on, these small productions seem more and more unambitious. Verini reused blocks from the Luminario which got badly worn. Although they are all slight, his pamphlets also got more and more miscellaneous. Some, like his Really Fine Secrets and Methods Newly Studied (Secreti et modi bellissimi nuovamente investigati), are not really instructional books at all but mere parlor amusements. (58)

Closer to Verini's schoolroom are the Work Most Useful for Learning to Write (Utilissima opera da imparare a scrivere), produced while Verini taught in Venice (probably between 1526 and 1532); a Tuscan word list of 1532 called Dictionario which was probably a sort of calling card for his new school in Milan; and two (or possibly three) versions of a small writing specimen book that Verini produced while he was teacher at Milan (between 1532 and 1538). Taken as a series, these works betray a career in decline. (59) In content Verini's pamphlets are dizzyingly miscellaneous, mixing rough pictorial woodcuts, calligraphic specimens, oversize initials, and occasional typeset texts. Some of the pieces in these books do not relate to any kind of writing or reading; instead they advise about how to behave in various social situations. This courtesy-book stuff is a clue to how Verini must have expected these booklets to be used. They are occasional practice pieces for boys in his school and edifying, "finishing" exercises for his lady students. Both these kinds of students are explicitly mentioned in these later books. (60)

Many calligraphic books of the sixteenth century reused woodcut specimens from earlier books, sometimes books issued very recently. Ugo da Carpi and Eustachio Celebrino, engravers for Arrighi and Tagliente, reused and re-cut their best blocks for books issued under their own names. Giovambaptista Verini, however, seems to have been the greatest master of this kind of adaptive reuse. Stanley Morison calls it plagiarism because Verini in the Luminario of 1527 presented copies of specimens from Arrighi and Tagliente and took over his titles from earlier works. But plagiarism is not an appropriate construct to apply in such cases. The period saw so many new calligraphic models come on to the market, both in classrooms and in print, that writing masters of the period could pick and choose freely among available models. Privileges were granted for these books, but they did not protect the content in any significant way. The point of a writing manual, after all, was to encourage its readers to copy the models it offered. (61)

Verini's habits of reuse are evident even in his most original works, since like many artists, printers and publishers, he happily re-employed woodcut blocks designed for one purpose in other, later books. The most striking case is that of the alphabet of large, flourished initials in a Low-Countries gothic style, each of which occupies half a page of his Luminario. These gothic capitals recur in almost every subsequent book of Verini's, where they are displayed on much smaller pages but never to the same purpose as in the Luminario. (62)

As with abaco books, then, the smaller and more elementary the writing book was and the fewer the pretensions it had to a broad audience, the more likely it was to be derivative and out of date. To some degree this was an inevitable consequence of the process of popularization inherent in composing basic textbooks and practical manuals, especially when they were translated from Latin originals. But among authors of language-skills books there was also a distinct element of condescension. No matter how strenuously they professed to be liberating their students from the tyranny of the "Empire of Latin" (Françoise Waquet's term), language teachers subscribed to the commonplace that vernacular-only instruction was for second-class students. (63)

This condescending stance stands in contrast to the optimism and can-do attitude of many popularizing how-to books for scientific and craft disciplines produced in the same period. These always included a great deal of traditional lore, but they often also reported new techniques and theories within a few years of their devising. Unlike language study where claims of novelty were almost always trumped up, authors in these truly new disciplines of the age of print were not wedded to the past and instead saw the potential of print for diffusing new knowledge. We considered the case of humanist geographies that brought discoveries into the classroom (in section 4.16). More popularizing how-to books offered the pleasure of owning new facts and methods personally in the form of an inexpensive book, of "taking knowledge, literally and figuratively, into one's own hands." (64) Upper-end writing books, as we have seen, strained to achieve the same progressive air, both in the presentation of new fashions in writing and lettering and in claiming new social status for their authors. By contrast, elementary writing books display a pedagogy wedded to the past. Writing was a skill with an increasingly large public, but one that should, these authors thought, be divided and segregated by class and gender.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (57) Verini 1527 and 1947; further on Verini, Morison 1953; Gehl 2008a.

- (58) Verini 1528.

- (59) Verini 1530, 1532, 1536a, 1536b, and 1966, 7-18; Morison 1953, 43; Gehl 2008a, 47-50. Further clues to his real status at Milan might emerge from reading an occasional piece in honor of his patroness Maria d'Aragona which I have not been able to consult; see Sandal 1988, 47-48.

- (60) Verini 1536a; Gehl 2008a, 48-49.

- (61) Morison 1953, 44-45; Verini 1966a, 36; Witcombe 2004, 285-291; Gehl 2008a, 42-44. More generally on imitation, copying and adaptive reuse, Barberi 1981, 94-103; Cherchi 1998,13-24; Quondam 1998, 14-26; Eamon 1994, 96-105; Witcombe 2004, 53-72; Petrella 2007, 46-60, 117-127.

- (62) Gehl 2008a, 50-66.

- (63) Waquet 1999, 410-412.

- (64) Cormack and Mazzio 2005, 24; see also Macagni 1993, 635-636; Eamon 1994, 94-102.