6.03 Commercial Skills

Tagliente's mathematics textbooks were all co-authored since, by his own admission, he was not himself a specialist in the field. They were neither the first nor the best of the sort, but they are typical of the self-help or how-to genre, by contrast to advanced works, but also distinct from more comprehensive elementary math books. Tagliente co-authored his Showpiece for Arithmetic (Luminario de arithmetica) about 1525 with a reckoning teacher, Alvise Fontana, otherwise unknown except that he also collaborated with Giovanni Antonio's kinsman Girolamo. The Luminario is based on the most up-to-date academic treatise, *Summa de aritmetica *of Luca Pacioli (ca. 1445-1517). (12)

A good index of whether any basic arithmetic was aiming at a non-expert audience or attempting to be more comprehensive is the degree to which its author simplified Pacioli's lengthy theoretical discussions. For the Luminario, Tagliente extracted just a few practical exercises on bookkeeping from Pacioli and offered them to merchants in strictly utilitarian form. He included only real-life examples of commercial problems. His title, Luminario, tells us from the start that Tagliente considered it a how-to book, with "displays" of useful information, in this case bookkeeping.

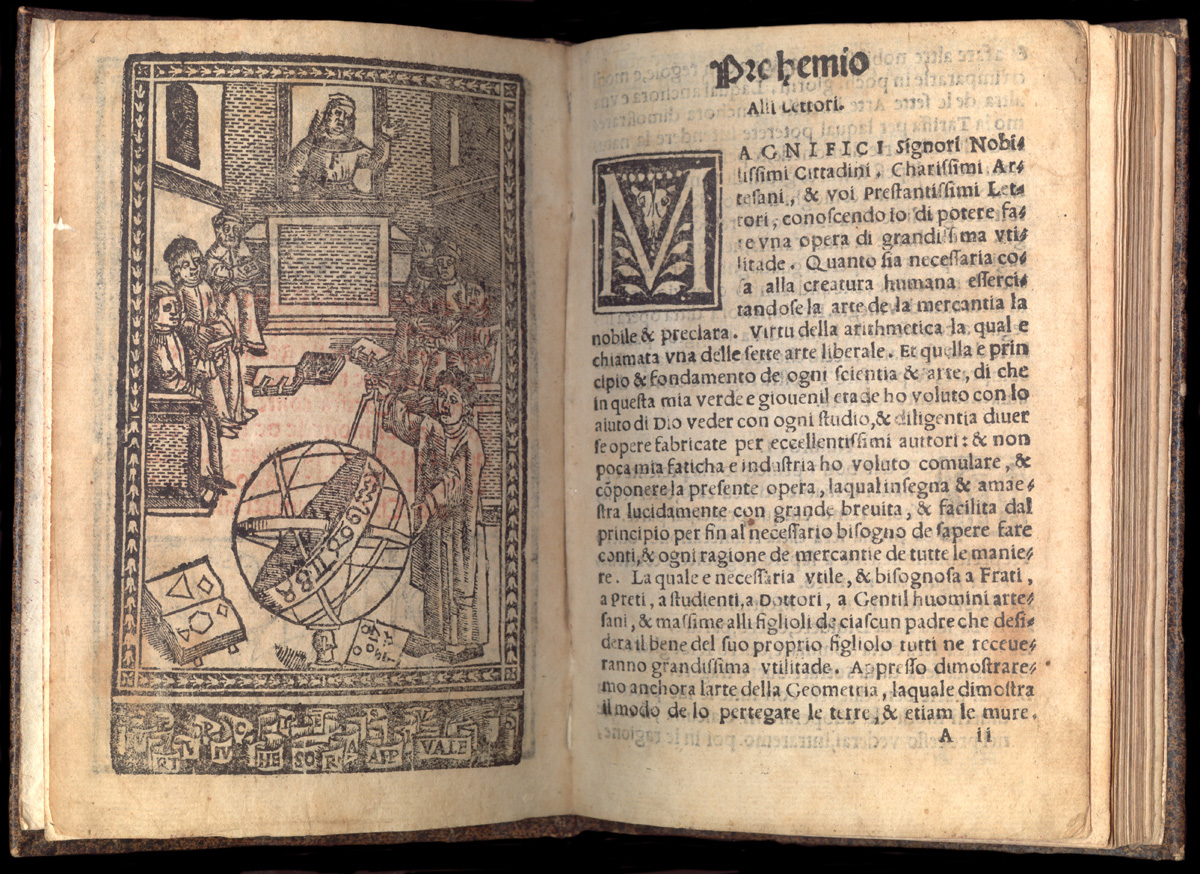

Bibliographers rightly treat the Luminario as two different books with the same title. One concerned simple, single-entry bookkeeping for shopkeepers; and a second book dealt with double-entry and considered a greater variety of business situations. The two booklets, although separately issued and each with its own dedication, are similar in typography and were clearly intended to be part of a suite of small textbooks that began to appear in the mid-fifteen twenties under the Tagliente family name. The fact that they have the same title suggests that Tagliente considered them a single work in two parts. It is interesting, then, that his prefaces specifically directed the single-entry book to artisans and shopkeepers, while he addressed the slightly larger book on double-entry "to our magnificent gentlemen and other merchants." For Tagliente, bookkeeping was a single subject that could have two different, if not entirely distinct audiences. (13)

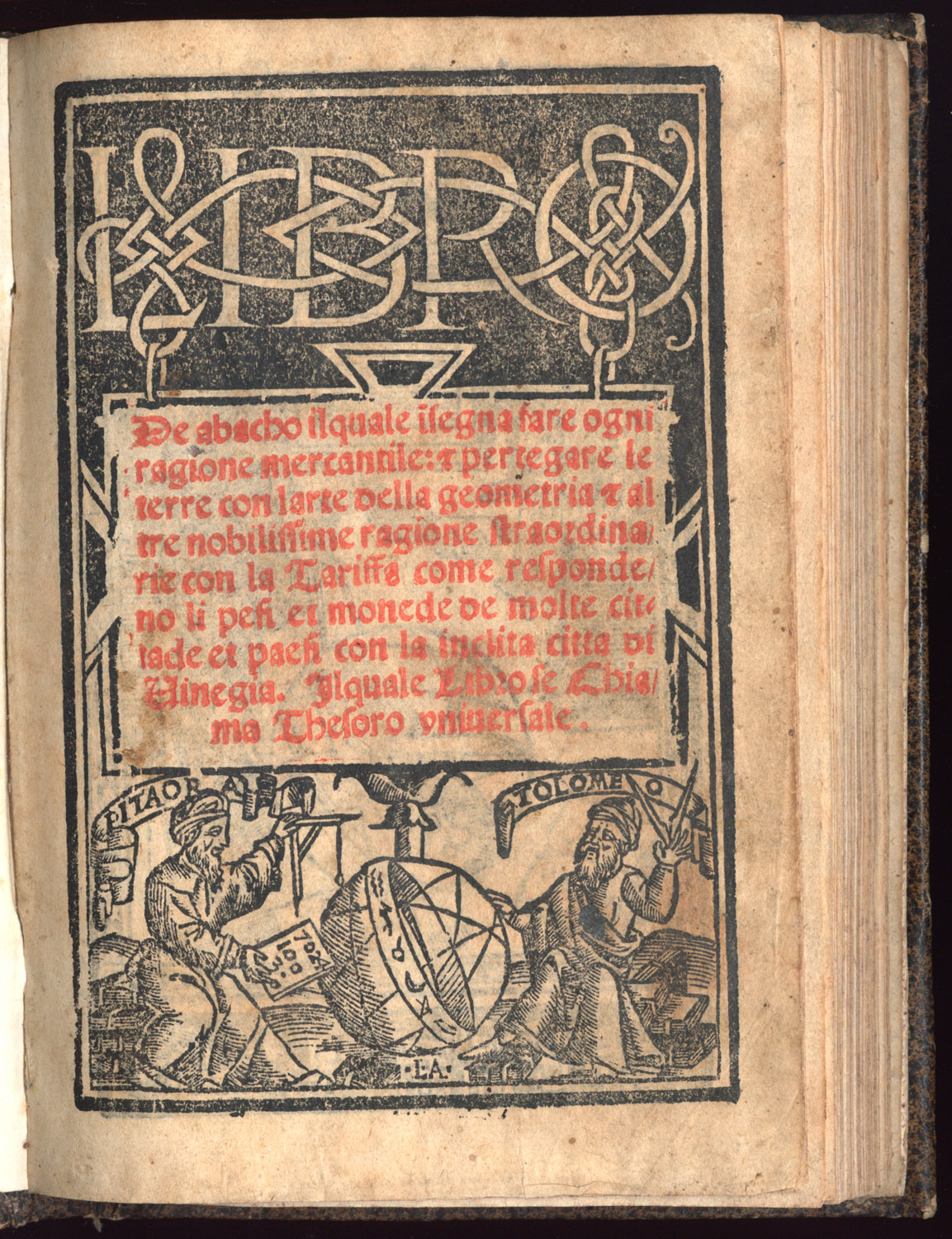

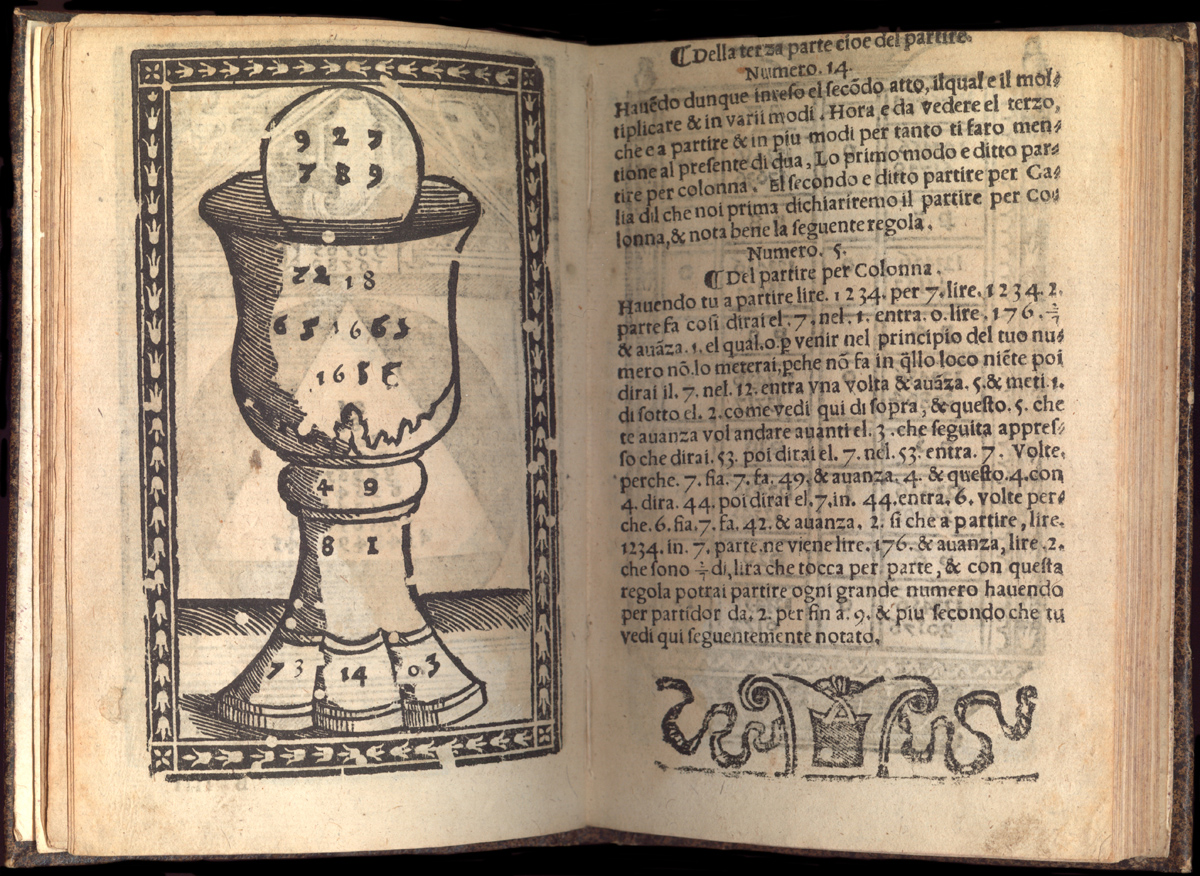

One unusual aspect of Giovanni Antonio Tagliente's achievement was family collaboration. A second, highly successful mathematics textbook that bears the family name was authored by Girolamo Tagliente (dates unknown) who mentioned the help of his teacher and kinsman Giovanni Antonio. We may discern Giovanni Antonio's distinctive voice on the wordy title page. It starts with a descriptive, generic term, A Book on Commercial Maths..., and only six lines later gives the formal title, Universal Treasury. It is unclear how much else Giovanni Antonio contributed to the original form of this textbook, which first appeared in 1515, but he is generally regarded as its co-author. The book treats a few basics in highly summary form: simple arithmetic functions, money systems, the computation of interest, practical plane geometry, and international exchange rates. This Thesoro, though much more extensive and systematic than the Luminario, similarly avoided theory in favor of problem solving. A large part is taken up with multiplication tables, presumably for memorization, but also, given the pocket size of the book, for visual reference. It is hard to imagine a reader learning from the book entirely on his own. The treatment of multiplication "by columns" for example, provides several diagrams, including one in the form of a chalice and host, but does not explain the method, saying only that it will be clear from the diagrams. (14)

In 1525, no doubt as part of a program of developing small, pretty textbooks en suite that also produced the Luminario, the Libro maistrevole, and the famous Tagliente handwriting books, Girolamo revised and enlarged his Thesoro to make it conform more closely to the common reckoning-school curriculum. The preface to this Principles of Trade (Ragione di mercantia) acknowledged the help of Alvise Fontana who seems, therefore, to have been a mathematics consultant to the Tagliente family. The Ragione preserved the structure of the 1515 Thesoro but considered the basic math functions more thoroughly and offered better practical advice. In the multiplication section, for example, the Thesoro diagrams are used to represent eight methods of multiplying, but while the Thesoro had left it to the reader to figure out each method, the Ragione parsed each diagram with careful instructions. The Ragione also conformed closely to the mature design sensibility of Giovanni Antonio Tagliente. (15)

The Ragione was apparently never reprinted, but the Thesoro in its original form received many editions. Only a few copies of any given printing survive, as is the case with most small commercial arithmetics. It is hard to tell how or if they competed with one another or with other books on the market. Still, it seems likely that books of the sort were produced in large numbers and that they had a long shelf-life in bookshops. One copy of the 1525 Ragione has the ownership mark of a velvet weaver who bought it, presumably new, in July of 1564. (16) Editions of the Thesoro continued to appear until 1586. The preface to a 1548 edition of the Thesoro from the presses of Giovanni Padovano seems to imply that the book had been off the Venice market for some time, but that assertion is hard to verify. Instead it was probably mere convention when the editor said of his copy text that, "soiled and marred by numerous stains, it had passed through the hands of many students of the arithmetical art" before he picked it up for reprinting. (17)

Padovano's editor also described the audience of commercial workers he envisioned, in a string of pieties more appropriate to the Venice of the Counter-Reformation than to the more secular-minded city that the Taglientes had inhabited:

This book is offered to those thoughtful and modest youths, whom it will please to study it with diligence (all agitation put aside). Finding it corrected in many places and with several pertinent additions, and taking pleasure in its convenient usefulness, they will take care to give thanks to Jesus Christ, who has granted that they be able to work for the common benefit of good folk. (18)

The Tagliente math books, like others of Tagliente's textbooks, were precisely calibrated to teach discrete skills at a basic level and to exercise students with a limited number of problems to solve. The authors did not pretend to cover an entire field, nor were their books designed for a specific school course. The treatments are highly incomplete even for the limited fields they addressed. It may be that Tagliente had in mind to simplify these skills to the point where how-to manuals could substitute for professional tuition. More likely still, he intended them as pocket-sized books of reference that would remind adults what they had learned in school. Whatever his intent, his pretty little booklets found a ready market.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (12) On Pacioli, Antinori 1994, 11-25; Crosby 1997, 210-222; Ciocci 2003, 30-36.

- (13) Bariola 1897, 374-376; Tagliente 1978a: a li nostri magnifici gentilhomeni & adaltri mercantanti, trans. Morison and Potter 1968, 38-39. Compare Tagliente 1978b: a* diversi mercanti et a molti artesani li quali fanno le sue mercantie nelle loro botege*. Both books appeared in 1525. On the Venetian merchant class, Tucci 1973, 346-361.

- (14) The chalice is illustrated but not explained by Jaffe 1999, 74.

- (15) Jaffe 1999, 35-37; Grendler 1989, 306-317; Morison and Potter 1968, 34-35.

- (16) Tagliente 1525, copy at Perugia, Biblioteca Augusta I.N.325 purchased by Nicola di Michelangelo genuese tessitor di veluto.

- (17) Tagliente 1548: sporco, & da diverse macole fadato volitava per le mani de molti della arithmetica arte studiosi. Padovano's heirs repeated this assertion in editions of 1554 and 1557.

- (18) Tagliente 1548: Questo... se offerisce alli discreti, & modesti giovani, alli quali piacera (remosso ogni furore) con diligentia studiarlo, & ritrovandi molti luochi acconciati, & assai cose a questo pertinente aggionte havendone con il piacere, commoda utilitate, degneranno render gratie a Iesu Christo, il quale ha concesso poter a commune beneficio de buoni operare.