6.01 Class and Gender, In School and Out

Paul F. Grendler's 1989 overview of education in Renaissance Italy includes an important chapter with the title "Girls and Working-Class Boys in School." (1) This way of categorizing students fits the usage of the early sixteenth century perfectly. Giovanni Antonio Tagliente (ca. 1465?-1528?), for example, on the title page of a 1524 primer described his audience as "those who know nothing "“ young, old, and women." A decade earlier, Gian Alberto Bossi had praised a bequest for a grammar school for poor boys by pointing out that it would make the unlikely possible, "The poor boy will learn as if he were a rich one." (2) These classifications were not condescending, just matter-of-fact, since entire social classes (and the vast majority of women) were only rarely given the opportunity to learn to read and write. Even if they achieved literacy, individuals in these groups were almost entirely excluded from the Latinate sort of education for which most early textbooks were designed. Educational (and publishing) categories were largely determined by gender and by class, though not in a symmetrical way. (3) Women and working class men were not completely barred from education, but they had few opportunities to go far in school. In the sixteenth century, vernacular textbook authors would come to appeal directly to such readers.

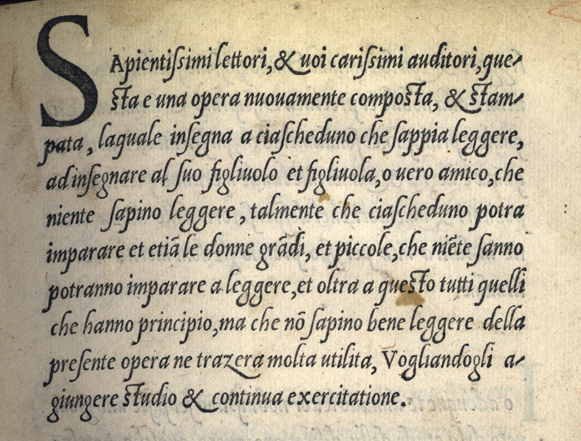

Tagliente elaborated on the kinds of non-Latin learners in a preface. First, he addressed his "Most wise readers and dearest listeners," in recognition that some in his audience could read with facility while others could not. Then he claimed that he intended with this book to make it possible for anyone who knew how to read to teach anyone else who could not ("even women" he added: etiam le donne). Moreover, his book would be useful for self-study by "all those who know the beginnings but do not yet read well." (4) Tagliente not only divided the social world of readers vertically among those who read Latin and those who did not, but he also delineated several categories among non-Latin readers, not all of them equivalent to differences in social status. Vernacular-only readers could be female or male (but not professional men). They could be looking to master simple reading skills or to achieve some level of facility in reading. They may or may not also have aspired to be able to write. This last category, furthermore, included some seeking to write in an elementary way, others whose ambitions were to facility, and even men (and more rarely, women) who aspired to write for a living, as scribes. (5)

It is also clear that Tagliente was not composing a textbook in the sense of a book intended for use in a school. The schooling he imagined involved a parent teaching a child or, as he repeatedly added, a literate adult teaching an illiterate friend. The logic of this, of course, was that relatively few non-Latin schools existed. Not surprisingly, therefore, there were few vernacular textbooks before the invention of printing. Such texts as came to exist were often self-help or how-to manuals. This chapter will concern a broad range of non-Latin instructional books. It does not attempt to be comprehensive, merely to give some examples of the variety of publishing for learners outside the elitist, establishmentarian Latin schools.

Tagliente's complex understanding of the public for his textbooks was possible only because he stood at the end of a long philological achievement, the humanist invention of a carefully periodized history of Latin and its descendant languages. The humanists had discovered that language was socially determined. They understood that languages were the products of speech communities that could be large or local and that varied from social class to social class. (6) An author, then, might well conceive a specific public for a given book, but once it was offered on the open market, its audience could vary greatly. Once a text was annotated, commented upon, translated, or reformatted it became a new work with a new audience. This understanding stood behind the successful marketing of Latin textbooks and it would become important to the development and marketing of learning tools in the vernaculars.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (1) Grendler 1989, 86-108.

- (2) Libro maistrevole, Tagliente 1524d, 3: li grandi & li piccoli & ... le Donne che niente sanno; this translation is that of Anne Schutte 1986; later in this chapter I also follow her translations. Bossi's poem is edited and translated by Marzorati et al. 2003, 72: Discit inops quantum si dives.

- (3) This asymmetry had also been true of the Middle Ages. Dante was explicit about it in the Convivio, fully two centuries before Tagliente: Cestaro 2003, 70-72. See also Farenga 1983, 403-405; Witt 1995, 84-87; Stevenson 2005, 143, 152-156. Cornish 2000, 170-178 explains how the late medieval female audience differed from that of the sixteenth century and the degree to which "vulgarization" aimed at a particular non-Latin elite, not merely a broader audience.

- (4) Tagliente 1524d.

- (5) Well nuanced discussions of social class and educational norms are those of Matthews Grieco 1991, 34-38; Lucchi 1992, 124-127; Maccagni 1993, 643-647; Ortalli 1993, 60-70; Trovato 1994, 24-35; Houston 2002, 141-171.

- (6) Waswo 1999, 410-412.