4.18 Geography in Italian Classrooms

Other Northern geographies had mixed success in Italy. Repackaging with a Venetian imprint, it seems, was the best way to sell them. The single most influential geography manual of the sixteenth century was the Cosmographicus liber of the German humanist, mathematician, cartographer, and printer Peter Apian (1495-1552). First published in 1524, his Cosmographer's Book (Cosmographicus liber) covered basic terrestrial geography, cartographic principles, and simple astronomy, and was supplied with numerous maps and diagrams. It is prized by modern collectors for its volvelles -- movable diagrams that illustrate the heavens. Early readers appreciated such devices too, since they were carefully reproduced in dozens of editions. Italians knew and studied the Cosmographicus liber but it was never printed in Italy, suggesting that its audience in the peninsula was largely expert. The larger Italian public was looking for something else.

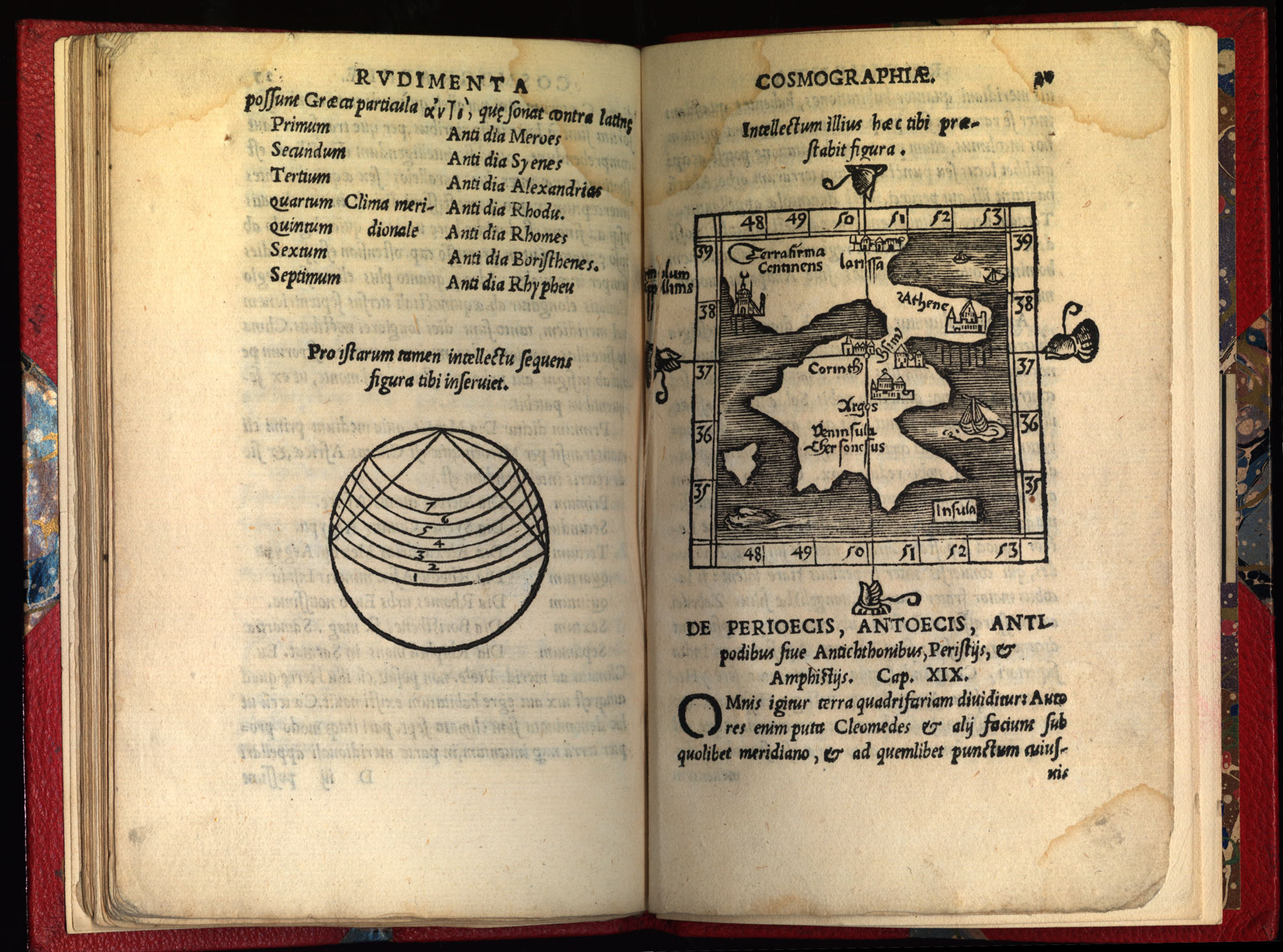

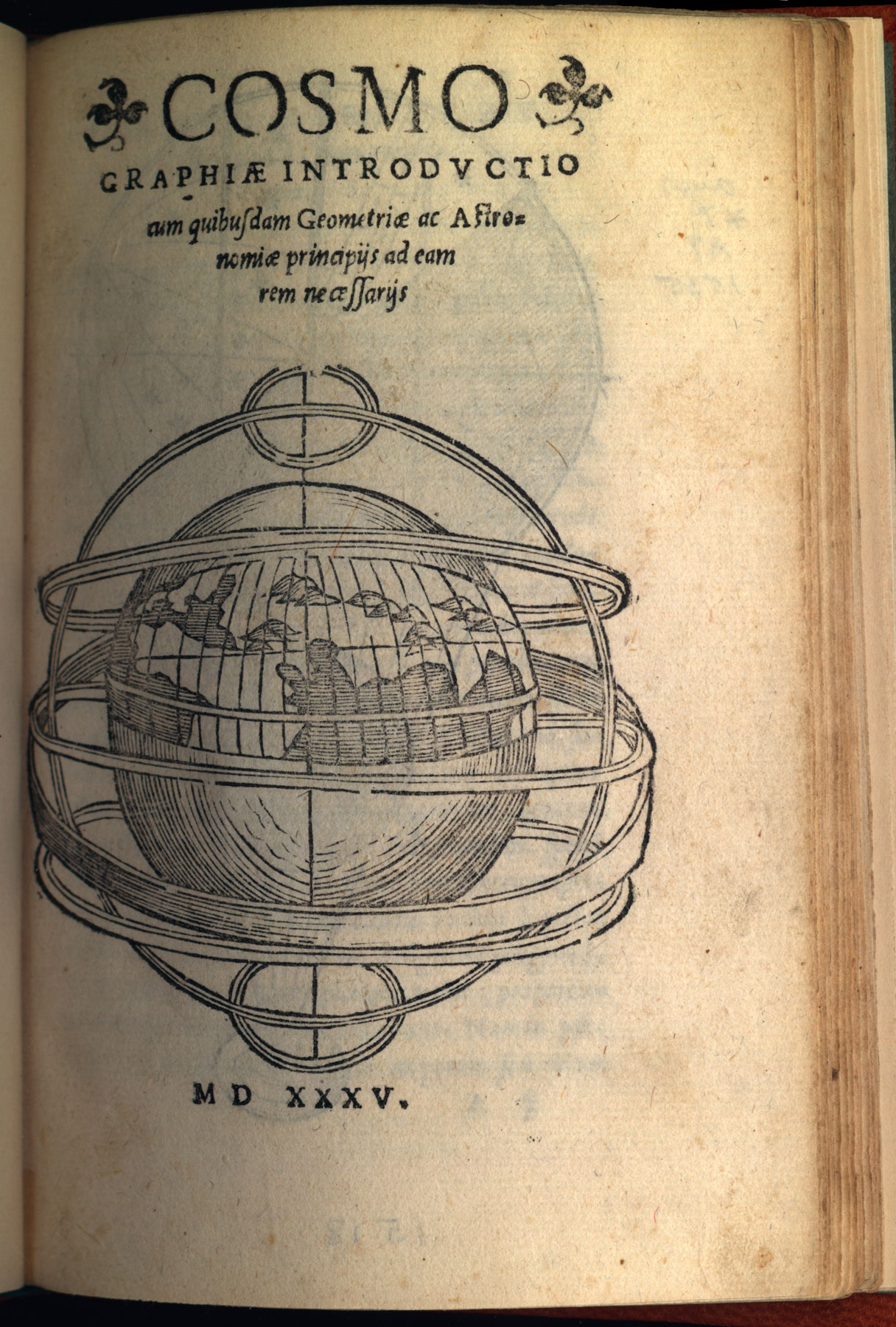

Apian himself prepared and printed an abbreviated version in 1529 under the title Introduction to Cosmography (Cosmographiae introductio). A true textbook intended for Latin-school students, it had fewer and simpler diagrams than the larger Liber.

As a result, it was much easier to reprint, and it got at least six Venetian editions. (76) There is little direct evidence for the way it was used in Italy, but the format and scope of this short work seem to conform to an Italian sense of how much geographical knowledge a humanist-educated layman would need. Clear, up-to-date concepts and a store of basic facts would allow a bureaucrat or gentleman to use geography in everyday cultured discourse. He could turn to experts when he needed deeper and more technical skills -- to navigate a ship, to predict a sunrise or an eclipse, to draw a map, or to cast a horoscope.

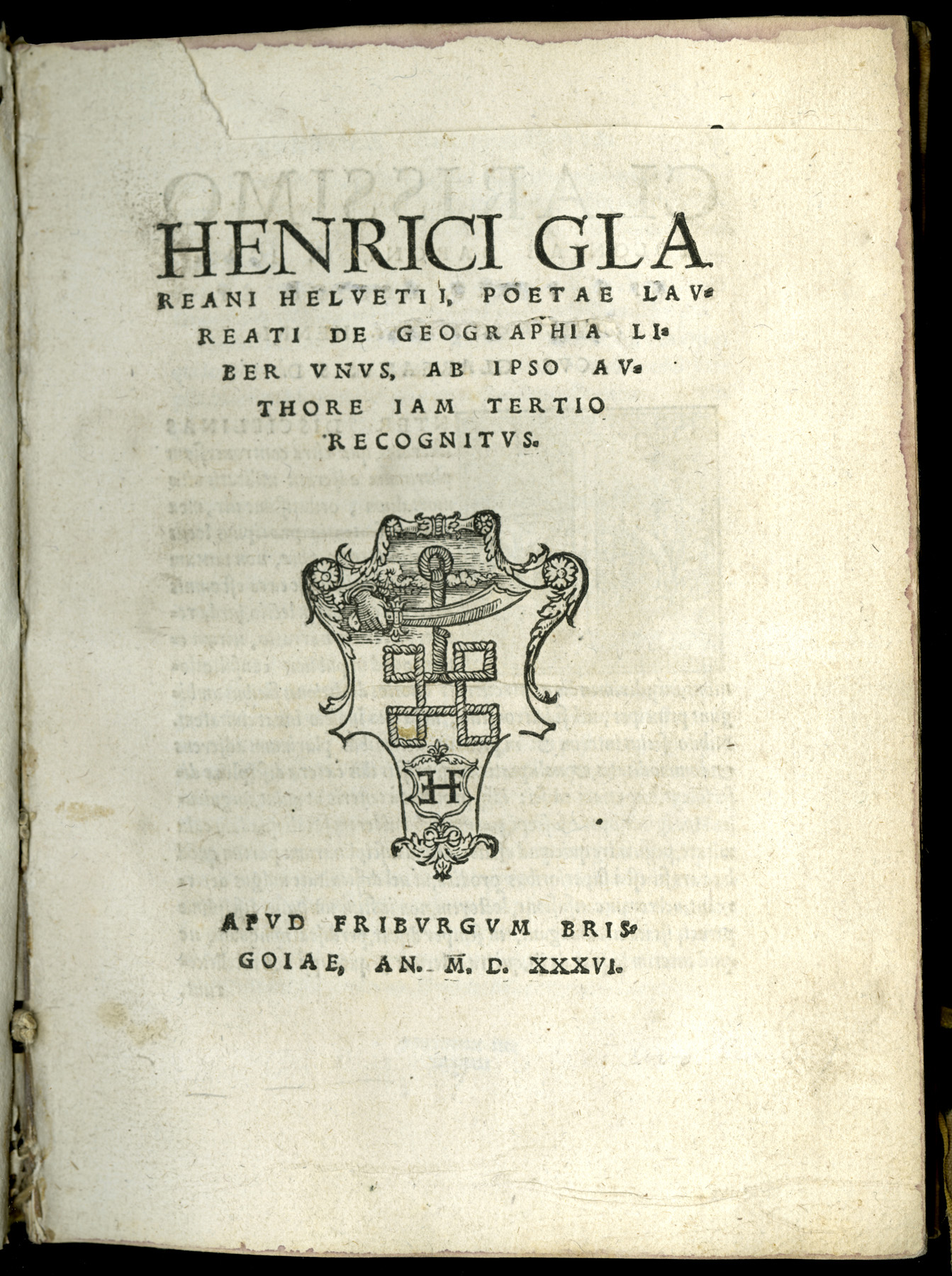

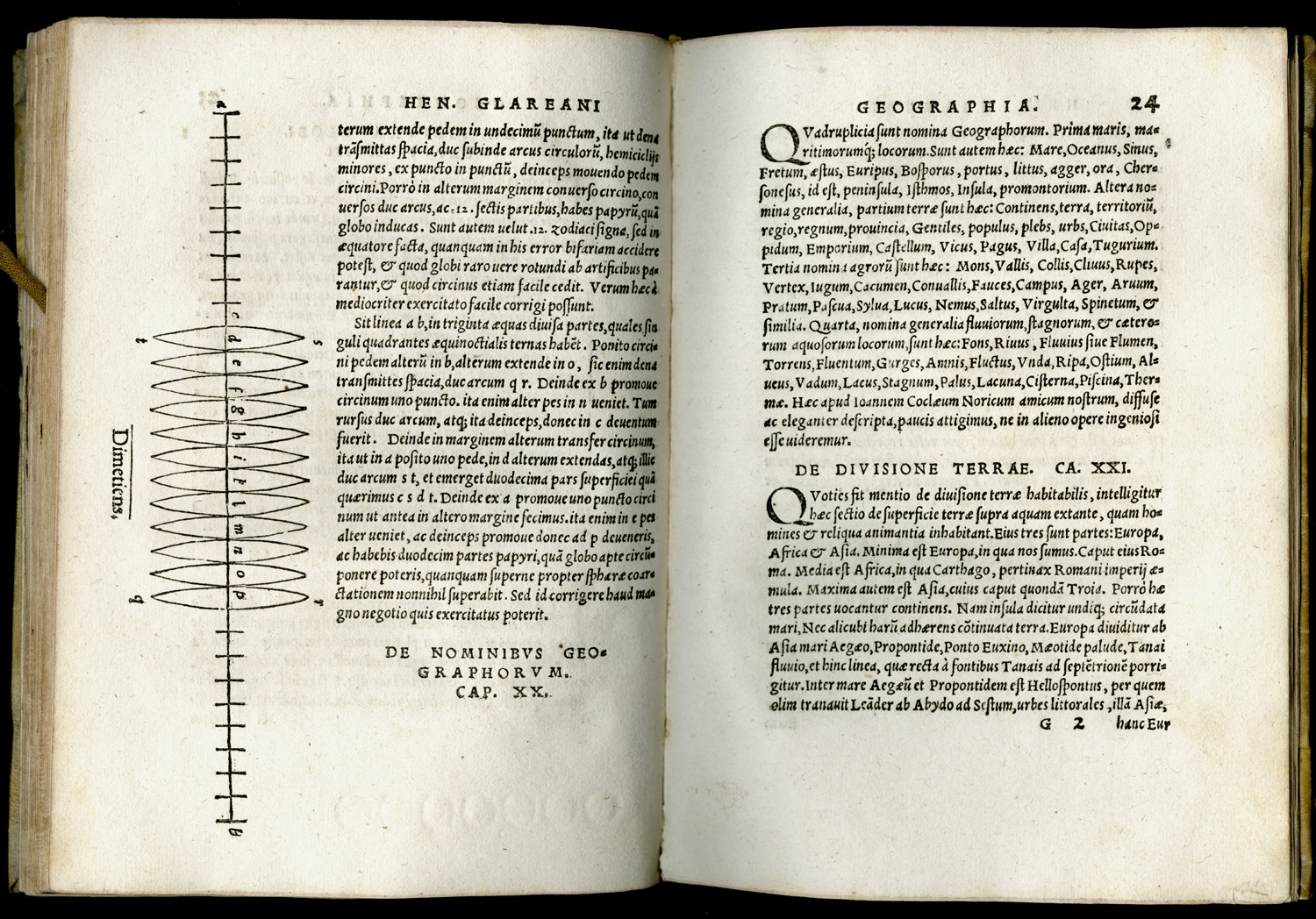

A very similar publishing history characterized another influential geography textbook, the De geographia of Heinrich Glareanus (1488-1563), a Swiss humanist and university professor at Freiburg. Like the same author's basic music textbook (treated in a section 5.18), this seventy-page geography was designed for students in humanist schools. It covered terrestrial geography only and stuck very much to the basics because, as the author remarked in his preface, geography is one of the liberal arts, useful above all in the deliberations of citizens and as an ornament to public life. Despite this seemingly modest aim, Glareanus did not want his students to be mere dilettantes. His text was very much up-to-date with the state of geographical knowledge and technique. He included basic information about the newly explored lands of the Western Hemisphere; and he offered a clear and accurate description of mapmaking techniques. Glareanus advertised his work as briefer and more elementary than the important ancient sources for geography (he names Ptolemy, Strabo, and Proclus) and more accurate than other modern treatments. He claimed to have added information culled from other classical sources, among whom he named Pliny, Pomponius Mela, Macrobius, and Horace, a list that reminds us that humanist geography remained a literary pursuit even as it became more scientific. (77)

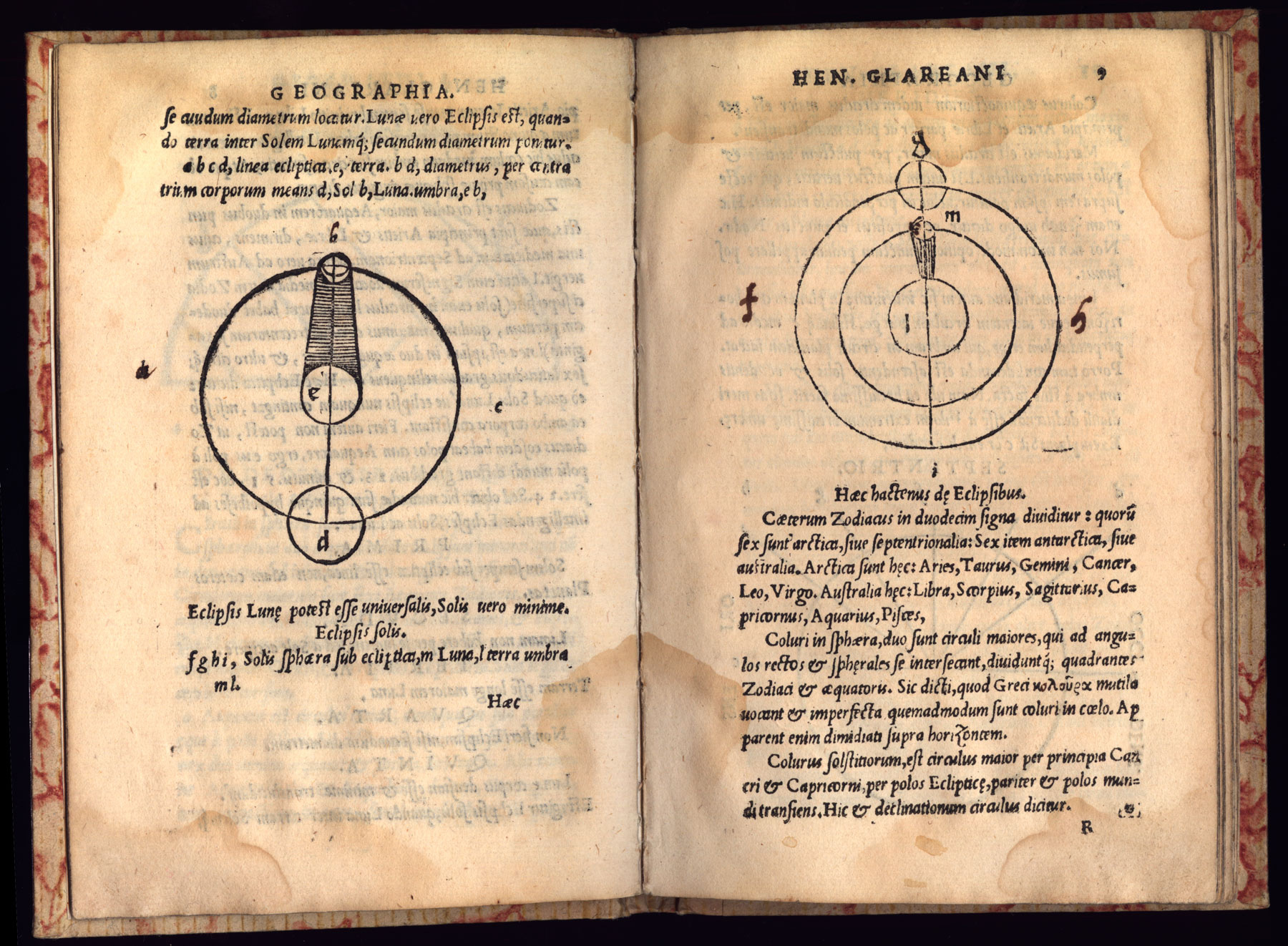

Glareanus's De geographia was published at Basel in 1527 and again in 1528 in a very sober and dignified typographic dress. The printer was Johannes Faber. His spacious quartos easily embraced both in-text diagrams and marginal ones. Later editions at Frankfurt and Paris retained this original format.

By the end of the fifteen thirties, however, Venetian presses were repackaging the work in more Italianate style. The Venice editions (the first dates from 1538) are all octavos. The narrow margins and reduced-size diagrams yielded books more crowded in feel and generally less elegant than the Northern editions.

On the other hand they are true pocket books, running to a mere seventy-eight pages and no more than sixteen centimeters in height. As in the case of Apian, the Venetian printers seem to have had a precise notion how to package geographical information for the Italian public. Their formula included the Italianate octavo, by 1530 a ubiquitous form in Italy both for poetry and for short treatments of serious subjects. (78)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (76) Karrow 1993, 52-56.

- (77) Fritzsche 1890, 91-93.

- (78) On the octavo form, see sections 1.08-1.11. Northern texts on scientific subjects had been repackaged for the Italian market from the late fifteenth century onward. For the example of Johannes Lichtenberger's astrological prognostications, see Fava 1930, 136-143 and Petrella 2007, 36-42.