4.15 Itineraries

In the final, fourth book of the Sfera, Dati offered something different and indeed entirely new, an illustrated itinerary of the Mediterranean Sea. It appears to be incomplete, covering only the southern and eastern Mediterranean and the Black Sea. Either it was unfinished at Dati's death or Dati considered it sufficient to deal with the major outbound destinations of Italian commercial travelers and pilgrims. The apparent gap was strongly felt by some readers, since it was remedied in part by an unsystematic continuation supplied by a Dominican friar, Giovanni Maria Tolosani (1472-1549). This supplement appeared as a separate in 1514 and was further enlarged for a 1515 edition of Dati. (64)

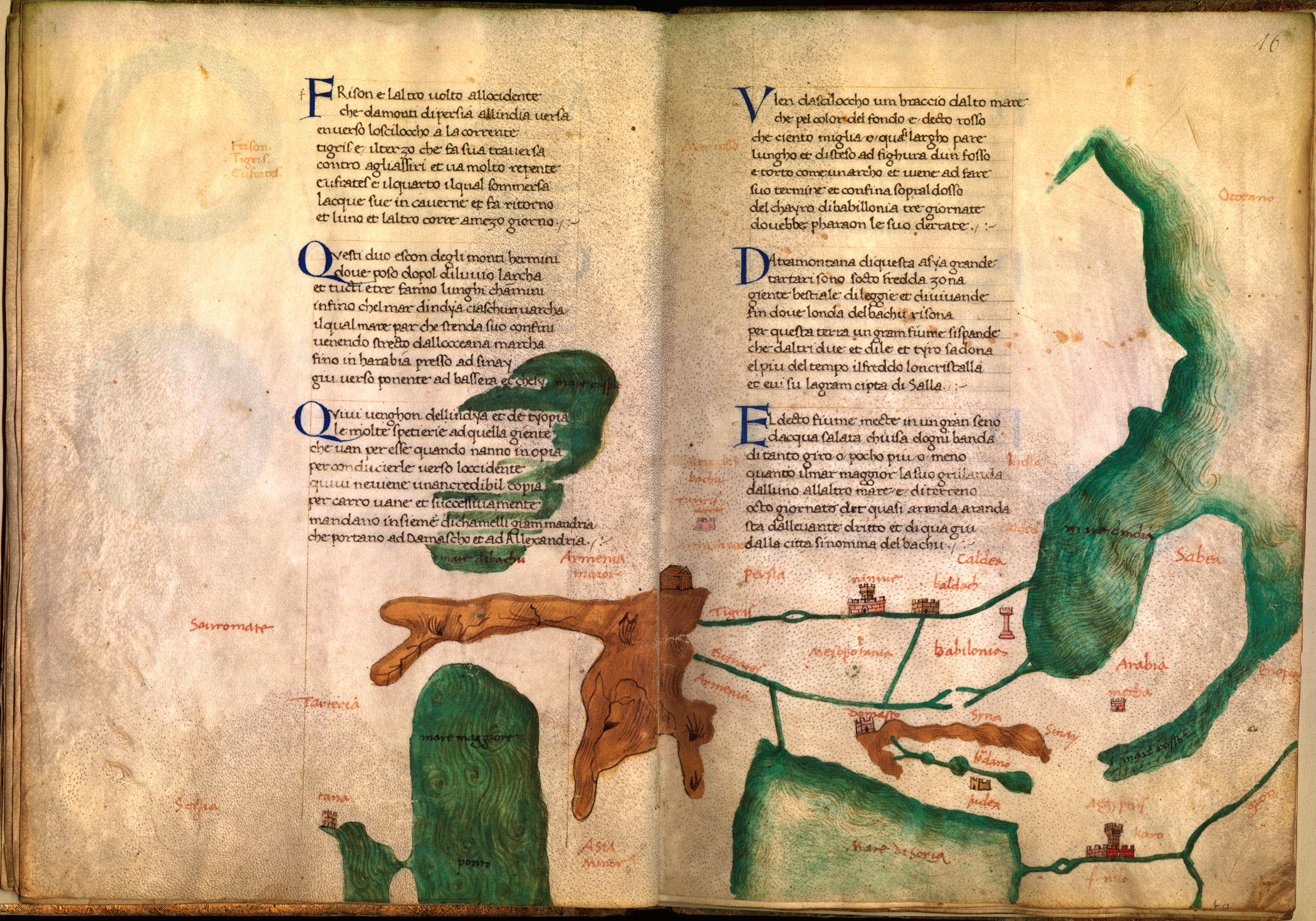

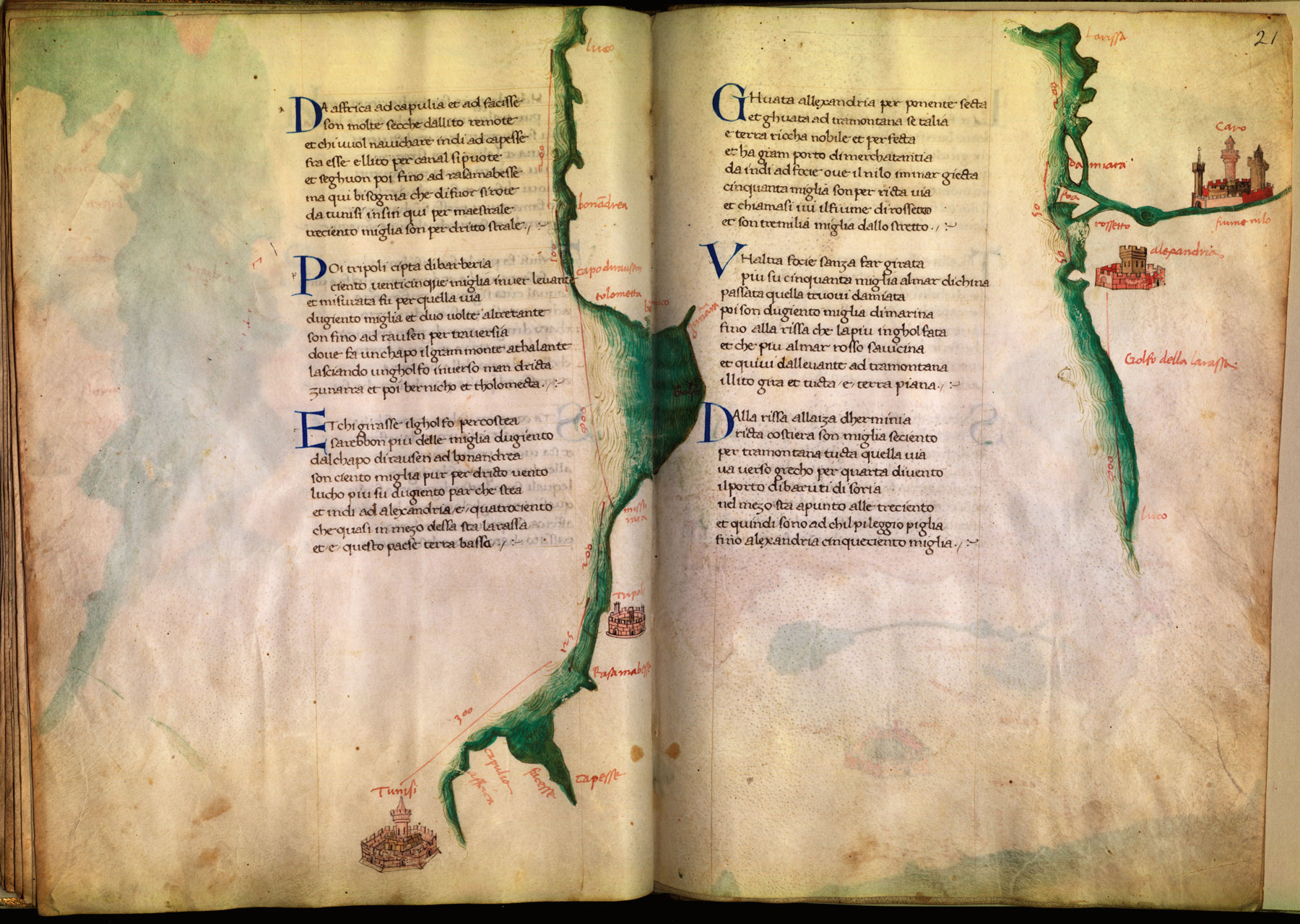

Dati's verse itinerary was intended from the start to be accompanied by detailed maps derived from the portolan charts used by ship's captains. Dati's scribes squeezed the maps into the margins, where they diligently illustrated coastlines and offered tiny city views of major ports. This kind of illustrated poem defies modern logic, both pedagogical and cartographic. Like the cosmological, "textbook" portion of the poem, it seems to have been intended as a mnemonic for the use of merchants, diplomats, or other voyagers to Mediterranean destinations. But it surely was not used by the sailors who were in charge of actually getting there. Both the descriptions and the maps are good enough to appeal to a literate traveler (either the real or armchair version) but not precise enough for navigators. (65) Like Petrarch's work, then, Dati's Sfera provided the traveler with a set of expectations that would allow him to make sense of landscapes populated by unfamiliar sights and exotic folk.

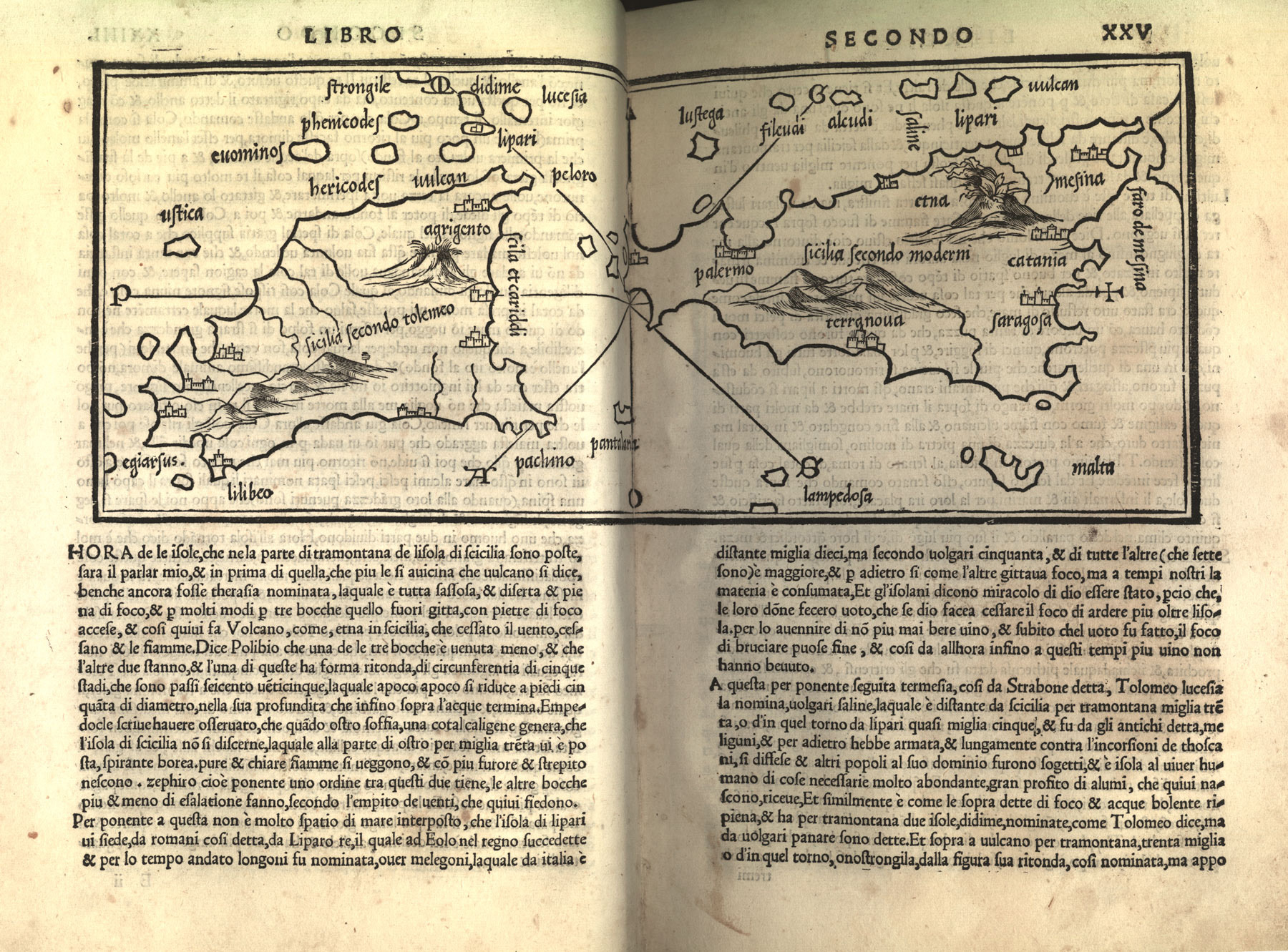

The last part of Dati's Sfera introduced the genre of a sailing itinerary illustrated with maps. Printed editions of Dati's work, in fact, omitted the maps and simplified the diagrams, suggesting that by the end of the fifteenth century the Sfera was no longer considered an instructional poem but merely a literary recreation. Editions of 1503 and 1518 bear a title that emphasizes this aspect of the poem, In this book is contained the power of the planets that govern the world, which book is called The Sphere. Certainly Dati's work was out of date. As geography, it could not bear the weight of its own elaborate illustrations. Later authors of itinerary-based geographies, however, took full advantage of the technical possibilities of printing to include the most up-to-date information in text and in maps. Italians came to call such travel-based geographies isolari or island-books, since the reader/traveler proceeded from port to port with stops at islands or other destinations not joined to Europe or Asia by land passages. This genre, with its somewhat misleading name, would survive into the sixteenth century and beyond. Isolari became ever more factual because their authors were increasingly informed by the European reconnaissance of Africa, Asia, and the Americas. But the form remained that of a guidebook and not a textbook. Thus, across a period of over two hundred years, Cristoforo Buondelmonte (writing about 1420), Benedetto Bordone (1450-1530), Tommaso Porcacchi (ca 1530-1585), and Vincenzo Coronelli (1650-1718) used the idea of an island-collection to organize compilations of geographical knowledge intended for non-professionals. (66)

Thus, it was for a general but well-heeled audience that Bordone provided his Book That Treats of All the Islands of the World (1528) with three large maps and one hundred eight smaller ones. He framed them rhetorically by saying that his was a work of topography devoted to the Mediterranean world, adding that topography is part of the larger discipline called Astrology. This science is founded on Arithmetic, Geometry, and Music and its parts are Cosmography, Geography, Chorography, and Topography. Topography for Bordone was a narrative form, following a journey, and as such it was the most literary of the many parts of Astrology. Thus framed, it was possible for Bordone to include all sorts of information, some of it highly miscellaneous, and to update the book as needed. In several later editions, he and his publishers made minor additions to the general factual content, and for the second edition (1534) they even included a bit of exciting geographical news, the conquest of Peru. (67)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (64) Tolosani 1514 was issued as a supplement to Dati 1513; the longer version of Tolosani's continuation appeared in Dati 1515. See also Dati 1859, 18-21, which is based on the 1515 edition; Segatto 1983, 157-159, 162-164. Further on Tolosani, Camporeale 1986, 146-153.

- (65) Auzzas 1986, 342; Clement 2001.

- (66) Conley 1996, 121-122, 129; Serafin 1996, 39-40.

- (67) Bordone 1534, preface; Karrow 1993, 89-93.