4.14 Geographical Fiction and Fact

We have seen repeatedly how packaging can affect the success of textbooks. This fact is particularly clear when a given book has to cross an intellectual border and find a market in a foreign pedagogical environment. Even if the subject is identical on both sides of the border, and virtually timeless like Latin grammar, authors and publishers had to work certain cultural translations to make the import work. Geography offers other instances of cultural translation, though they are much more complex than simply moving from Brabant to France to Italy, changing typefaces, or advertising to a different public. Geography started the Renaissance as a literary pursuit, an armchair science, but already in the early sixteenth century it was also a practical discipline, based on data that did not even exist a hundred years earlier. Moreover, this new data was pouring in almost faster than the presses could report -- from Africa, India, and the New World, and from new celestial observatories. Textbooks lagged well behind the knowledge curve, at least in part because the scientists and explorers had to accomplish so many other exchanges and translations before authors could attempt elementary treatments. In this chapter, there is space only for a few examples of textbook or textbook-like treatments. We will discover more limitations than achievements, and even more barriers than Latin grammars faced.

Literary geography derived from two traditions. First there were ancient and medieval travel narratives that had entertained Europeans for centuries. Secondly, an impressive but relatively recent humanist, philological tradition was devoted to deciphering place names in classical literature and providing geographical information in glosses to the ancient texts. (60) Only in the sixteenth century did anything like a basic geography textbook appear, and then only because writers began to see the subject as a practical discipline with information to absorb and skills to master -- a how-to genre -- rather than a primarily literary form. To the degree that geography remained proto-scientific, moreover, it was often treated in Latin and not in the vernacular. While many travel narratives were written in Italian, most geography textbooks were still composed in Latin up to the end of the sixteenth century. Only the most successful were translated.

Writing about travel was an important early Renaissance genre. No less a humanist celebrity than Petrarch provided a model with his guidebook to the Holy Land, in Latin, compiled entirely from literary sources for the use of a friend who would travel there. (Petrarch himself never did, and probably never even wanted to.) In content it is fairly traditional, recounting an itinerary in some detail but without reference to broader geographical context. Other writers of the fourteenth and fifteenth century also offered itineraries. Those in the vernacular were usually versified. It was, if not a distinct literary genre, a fairly common and popular form offered to a variety of armchair travelers in the early Renaissance. (61)

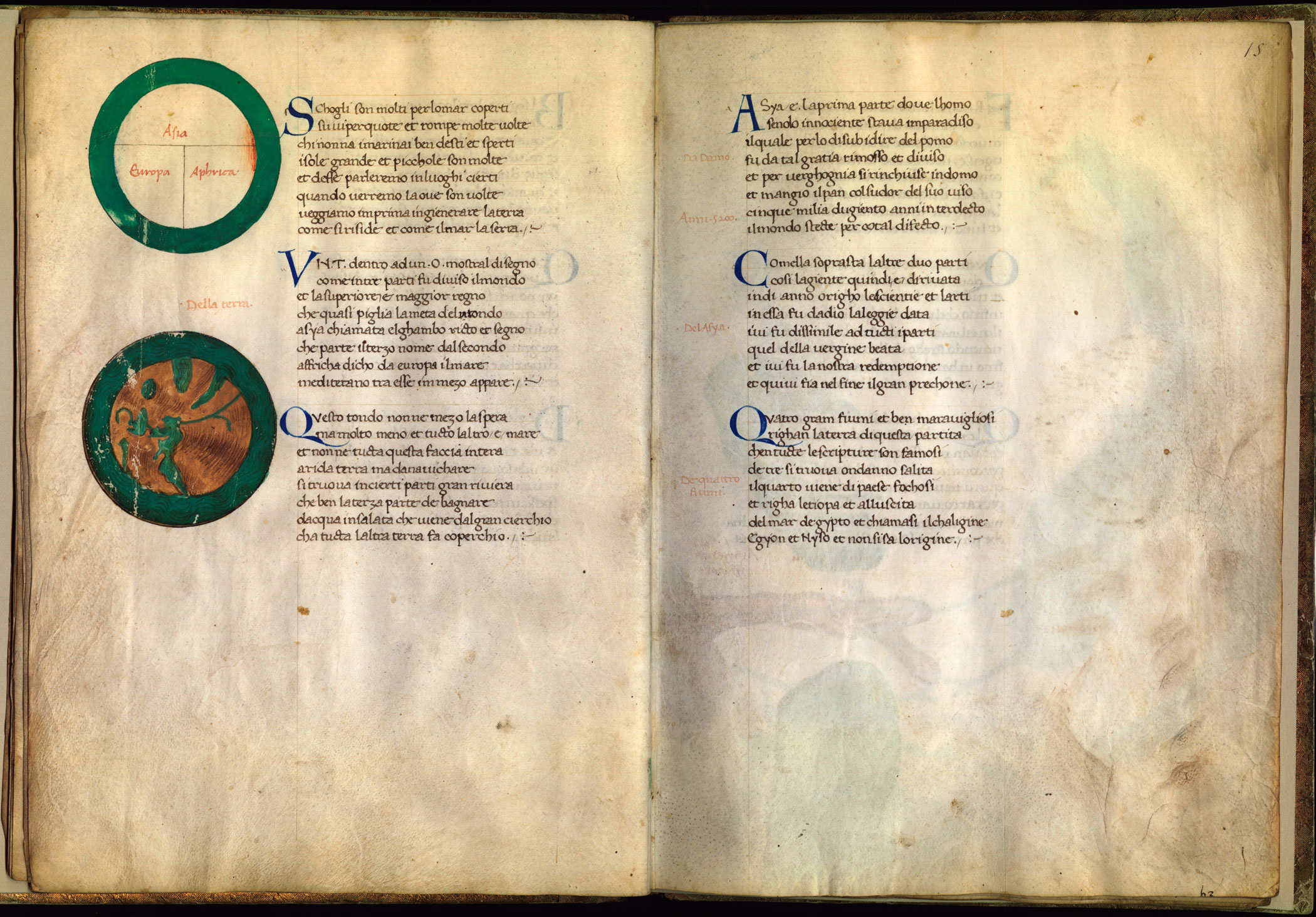

Somewhat more practical than Petrarch's guide but still highly literary was the Sfera of Gregorio Dati (1362-1436). This 1152-line poem starts with a general introduction to the shape of the cosmos. Later sections treat of the climates and seasons, navigation, and the continents and seas. It was the first vernacular text to offer such lore to a non-Latin audience, and it was widely popular. More than two hundred manuscripts survive and eighteen editions appeared up to 1543. The poetry itself and the contents of the surviving manuscripts suggest that the public for the piece was not humanistically trained. Dati's were readers of the merchant classes, comfortable reading Tuscan but not Latin. (62) To modern eyes, the work reads very much like a textbook. The competent but unpretentious ottava rima verses reinforce this sense, since texts to be memorized by students were regularly versified. Many manuscripts are richly illustrated with diagrams and maps in text, another didactic strategy that relates the Sfera to more scientific texts of the early Renaissance. Although it does not fit any known school curriculum, Dati's Sfera does fall into a category we might call moral-didactic. It is a reminder that how-to books did not limit themselves to actually making or doing things; they also set out to teach people how to live well and virtuously in a geographically defined real world. (63)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (60) Petrarch 2002, i-ix.

- (61) Segatto 1983, 164-165; Auzzas 1986, 343-344; Cachey 1996, 62-64; Cornish 2000, 167-168: Cook 2002, 51-52; Petrarch 2002. At the far end of literarry imagination stands the "travel" narrative of Fazio degli Uberti, an allegorical journey through real places, probably aimed at a courtly audience; see Ragni 1986, 224-227.

- (62) Segatto 1983, 159, 174-178.

- (63) Segatto 1983, 152-154; Clement 2001; Cook 2002, 52-55.