4.13 Packaging Pedagogy Too

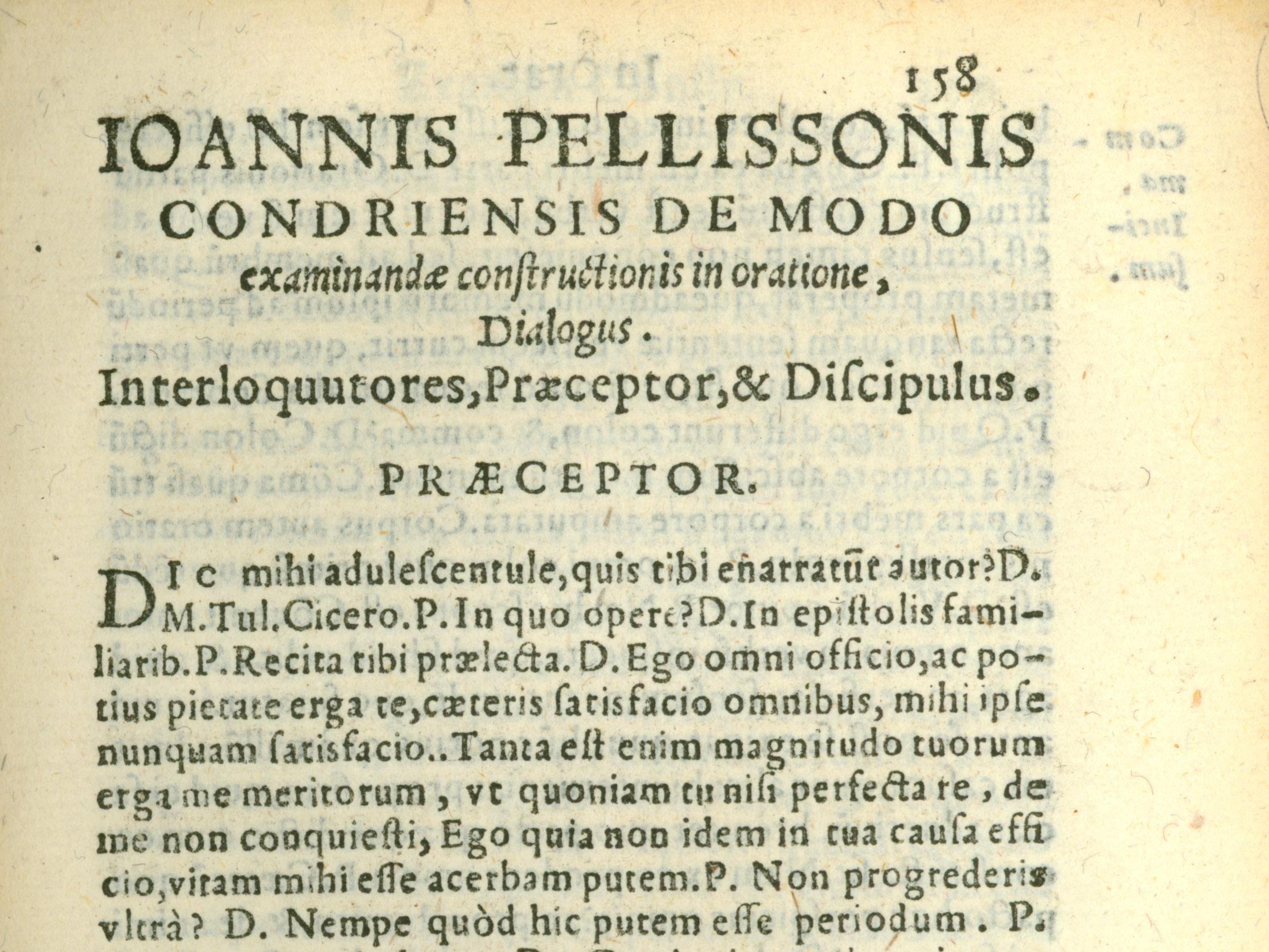

Textbooks, obviously, are always packages -- packages for didactic texts. Pellisson and his publishers, however, went further and tried to package the classroom experience itself. For example, some but not all editions of the Rudimenta contain an appendix on syntax that demonstrates a question and answer fashion of parsing literary texts. This appendix is a bit of an oddment in that it both offered an exercise in sample prose and also made larger claims. It is presented as a specimen classroom dialogue, showing what Pellisson imagined a good teacher would do in class when approaching a literary text. The speakers, a grammar master and a student, are reading the first of Cicero's Epistolae familiares together. The student is asked to read aloud, and we immediately discover that he has some experience in this parsing exercise because he stops at the end of a rhetorical period and says he is doing so. With prompting, he is made to define the meaning of "period" and provide an etymology for it. When he cites Quintilian and then divides the period into its parts, it becomes clear that this is no real student, but someone who has already mastered the rules which are the subject of the dialogue. The remainder of the exposition is detailed and systematic, so no one would mistake it for a real conversation, no matter how stilted. The fact that the typesetter of Lorenzini’s 1562 edition missed some of the dialogue cues and assigned some of the student’s words to the teacher and vice versa hardly matters. It is merely a rule book in another form.

Amidst all the definitions, however, Pellisson's teacher and student did manage to detail a procedure for reading literary texts. The text, in this case Cicero, is to be broken into periods and these are taken apart one by one. The student is to rearrange each period from classical word order into "scholastic" order, that is, according to the order of modern languages. This new order is understood very mechanically: vocative if any, nominative, verb with pertinent adverbs, and then any words governed by the verb. If there are words left over, the student must find a place for them within this rigid formula. To do this he runs through a memorized list of possibilities -- appositives, prepositional phrases, and subordinate clauses of various sorts. When every one of Cicero's words is accounted for, he goes on to the next period. Like diagramming sentences in a modern classroom, this method of analysis was repeated through many texts until it became second nature to the student. Thereafter it could be abandoned as a regular practice, but remained in mind as a fall back for approaching any difficult passage.

Pellisson, then, was a very modern packager. He prescribed a clear method for using the books he authored or edited, and he provided step-by-step instructions for using other, classical texts in the early stages of teaching grammar. His descriptions of method are fuller and more systematic than those we have seen in other grammar books, and they also conform to the developing norms for advertising textbooks that we have encountered. As neatly packaged as a sixteenth-century textbook could be, Pellisson's Despauterian grammar was both a practical pedagogy and a marketable commodity. In this form -- but really only in this form -- our Northern grammarians had some success in the Italian market. (59)

NOTE

- Open Bibliography

- (59) Deutsch 2002, 1013 presents evidence that "Despauterius," presumably in the form of Pellisson's Contextus, was the second most popular grammar in seventeenth-century Novara, rivalling the textbook of Manuel Alvares, S.J. which will be treated in chapter 5.