3.16 Packaging Celebrity

Tacuino's 1507-1508 collection was copied at Milan two years later in an altogether more systematic form. This collection had the patronage of publisher Leonardo Vegio, who had the means to command a fully integrated set of thirty one works in nine separate fascicles issued between July and December of 1509. These are again reprints of Tacuino's editions, but they have a prettified title page that reads Opera omnia and follows with a full list of works printed in black and red. (86)

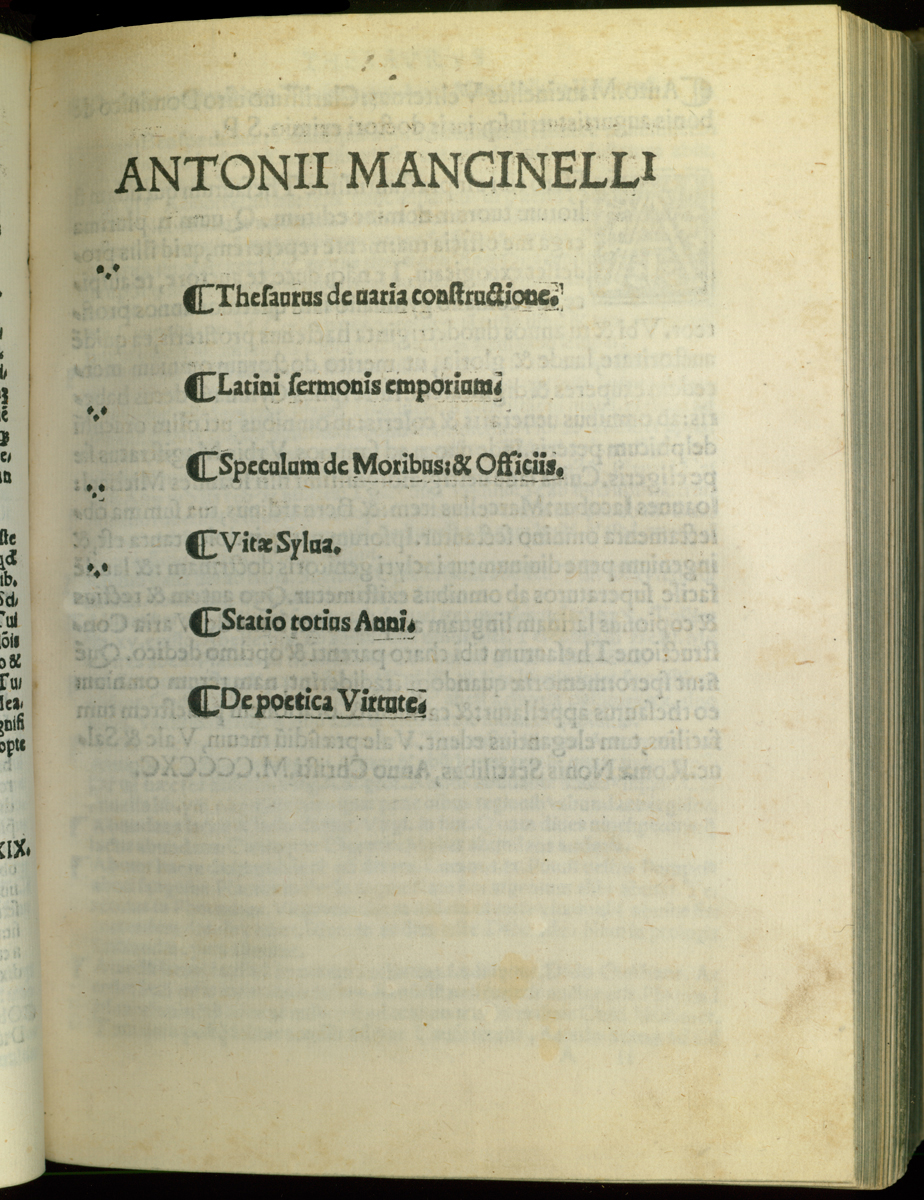

Leonardo Vegio's collection is important because it represents sophisticated packaging specifically for classroom use. Vegio gave each of the nine fascicles a separate title page so they could be had in the traditional form, as separates, if the customer wanted them that way. Indeed, we must suppose that for teaching purposes, students would normally be given one fascicle at a time. Some of the fascicles with a single title page are set and signed in such a way that they could be further broken down for classroom use. For example, the second fascicle has a title page that unites the Thesaurus de constructione, the Latini sermonis emporium, and the Speculum de moribus with other small moral poems. All are elementary works, but they would not necessarily be used in the same way or at the same time. The Thesaurus, in three gatherings, is signed a through c; the Emporium has a caption title and is gathered AA and BB; and the remaining small works, introduced by a new title page, run from aa to cc, three gatherings again. Even if it were only offered for sale as a single item, such an eight-gathering booklet could be separated for student use into three shorter pamphlets. Vegio and Mantegazza also imposed a uniform typographical style on their series, with regular use of types and carefully crafted running heads, so as to make for a genuine collection, usable as such. In the case of the fascicle described above, each separate work has running heads that make it clear where it begins and ends, simplifying consultation of the collected set and clarifying for the binder which leaves are which. All in all, these Vegio imprints are the most handsome presentation Mancinelli's school texts ever received. Another entrepreneurial Milan printer, Nicolò Gorgonzola, seems to have started yet another collected works of Mancinelli; seven titles survive. (87)

It was the Venetians' turn to play copycat in 1519 when Giorgio Rusconi reproduced the 1509 Milanese title page for still another collection, this time using versions of Mancinelli's works edited by Josse Bade. Although he copied many aspects of the Vegio/Mantegazza printings, including the running heads, Rusconi's production standards were not as high. The heads are often erroneous; the signing is confused; and although there are cross-references from fascicle to fascicle, they are as often wrong as right. Several works that appear on the title page are omitted entirely, and the texts are often badly corrupt. Alas, this sloppy and unreliable edition of Mancinelli is the version most frequently encountered in modern libraries.

.jpg)

Rusconi did add one refinement to the typography, a series of short titles on each printed sheet. In the bound volume these appear next to the signature mark at the bottom of the first and third leaf of each gathering. They serve in a limited way, in the fashion of running heads, to orient the reader or binder making his way through a set of unbound pamphlets with no printed folio numbers. In the fascicle corresponding to the one we described above for the Milan edition, for example, the same three works appeared in the same order. Instead of starting the signing anew in each subsection as the Milanese printer had done, Rusconi added the title THESAV.MAN (Thesaurus Mancinelli) to the bottom of the first and third leaves of signatures A and B, and SPECV.MAN (Speculum Mancinelli) to the first and third leaves of gatherings E, F, and G. Gatherings C and D have no such titles.

.jpg)

This practice, called a catch-title, was uncommon at most periods, but it had a certain fashion at Venice from the mid-fourteen nineties into the sixteenth century. (88) It makes best sense in the case of books stored in sheets in a bookshop, for it would allow the bookseller to pull only the sheets for a single work if that is all the buyer wanted. There is clear evidence that this was its meaning in Rusconi's shop. Apparently the 1519 Opera omnia of Mancinelli was available in three different ways. Rusconi offered individual works, composite units (two or three works each behind a single title page), and the series as a whole. The most common surviving form is the collected works with their Opera omnia title page. The composite fascicles also survive with some regularity. (89)

Single-work pamphlets survive much more rarely to evidence this shop practice of using catch-titles; or perhaps more precisely, pamphlets of the sort have rarely been identified and cataloged. They may in fact be common but misidentified. As it happens, just in the case of this 1519 Rusconi edition, two such single works can be found in Illinois libraries. One at the Newberry Library in Chicago is a separate detached from the Thesaurus/Emporium/Speculum fascicle just described. It contains just the Emporium. A second such separate is held by the University of Illinois. It contains the Epigrammaton libellus and derives from a fascicle that once contained the De floribus and De figuris. It is presently bound with a complete but different fascicle, one that contains the Sermonum decas and other prose works. (90) The fact that catch-titles, though common in Venice in Mancinelli's day, do not appear in any of his works as printed in his lifetime suggests that he did not approve of the practice. It is a purely typographic usage, unrelated to the classic look of humanist manuscripts. It may have been uncongenial to Mancinelli for that reason alone.

Although Rusconi's collected edition was very successful, other Venetian and Milanese printers did not simply cede Mancinelli's works to Rusconi. Giovanni Tacuino issued all the works separately between 1518 and 1526, and added an Omnia opera title page in the latter year to a Donatus melior. This time he copied the Milan edition, not Rusconi's. (91) Other printers offered individual works with some regularity for another thirty five years. The most popular would seem to have been the basic grammar unit, Regulae constructionis with Summa declinationis. First published as a combination in 1490, it got a printing as late as 1563 by Francesco Lorenzini. The presses of the Nicolini da Sabbio family issued this and other short works repeatedly between 1526 and 1550. In 1536, one large Milan bookseller had in stock no fewer than 358 copies of the Donatus melior, 709 of the Scribendi orandique modus, 198 of the Spica and 409 of the Speculum de moribus. (92) All in all, Mancinelli's was a remarkably long career for a textbook author. His most elementary grammar books were particularly durable. Apparently some teachers continued to take to heart the advertising phrase that Tacuino had put in Mancinelli's mouth on one of the first editions after his death, "Whoever wants to become learned quickly, let him study my eight little textbooks." (93)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (86) On Vegio, Sandal 1978, 53-60.

- (87) Gorgonzola, well known for copying the successful works of other Milan publishers, printed at least one Mancinelli title for Leonardo Vegio in 1509 and then, starting in 1511, began issuing others under his own imprint. In addition to six titles recorded in EDIT 16, there was a Speculum de moribus and related texts dated March 1517 that survives in an apparently unique copy at the University of Illinois/Urbana-Champaign. On the competitive climate at Milan, see Ganda 1998, 35-38; Petrella 1002, 164-165, 173. On the classroom use of separates, Gehl 2008b.

- (88) M. Smith 2000a, 73-74. Another suggestive case is that of Bienato 1521, a short work which may have been part of a larger publishing project; the latest example of the practice I have seen is Cantalicio 1542.

- (89) The University of Illinois/Champaign-Urbana, for example, owns four separate units from the 1519 Rusconi Opera. Most of the catch titles in the collection identify these units with a single catch-title throughout; only the Thesaurus / Emporium / Speculum unit has two different titles, as described above.

- (90) Newberry Library, Inc. 5548.8; University of Illinois/Urbana-Champaign, x875 .M311s. On these and other fragments, Gehl 2008b. On problems in cataloging such "separates," Sandal 2006, 62 n. 26.

- (91) See Mancinelli 1526, described in EDIT16 under the title Omnia opera.

- (92) Ganda 1988, 129-137. We must allow for the possibility that these large numbers of copies were unsold because Mancinelli's reputation was waning; but even if that were true they bespeak a relatively recent popularity in schools at Milan.

- (93) Mancinelli 1506a: Qui quaerit fieri statim peritus, octo iam relegat meos libellos. This is the last line of a poem that bears the title, Octo Mancinelli opuscula: Grammaticam, poetam, oratorem brevi efficiunt.