3.03 Printer's Errors

All these prefaces advertise the value of reprinted books, that is, corrected ones. Still, we notice a distinct difference in tone between Mancinelli's own words and those of his editors and printers. Mancinelli advertised by explaining and insisted upon the need for continuous correction. His boosters were less modest and more aggressive. They claimed Mancinelli's diligence as a corrector for their texts, even after his death.

One might expect that the writers of advertisements would gloss over the inherent flaws of the printing process, but exactly the opposite was true. All these writers in Mancinelli's orbit were pretty matter-of-fact about the way in which printing introduced and perpetuated errors. Indeed, they emphasized the bad texts that printing produced. Their very self-consciousness was a vindication of the processes of correction, revision, and enlargement that characterized the creation of successive editions of texts that were -- even in imperfect form -- highly successful. It seems likely that Mancinelli himself prompted this notion of continuous revision as a positive aspect of his works. (14)

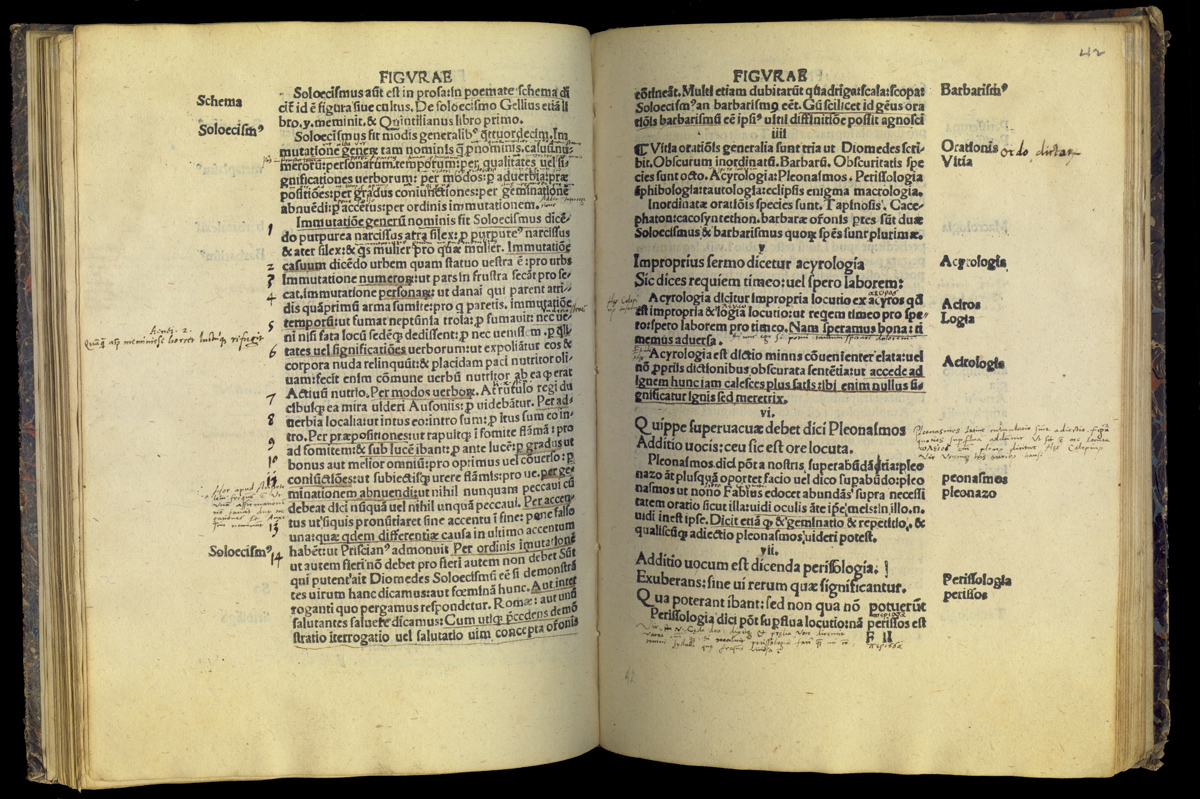

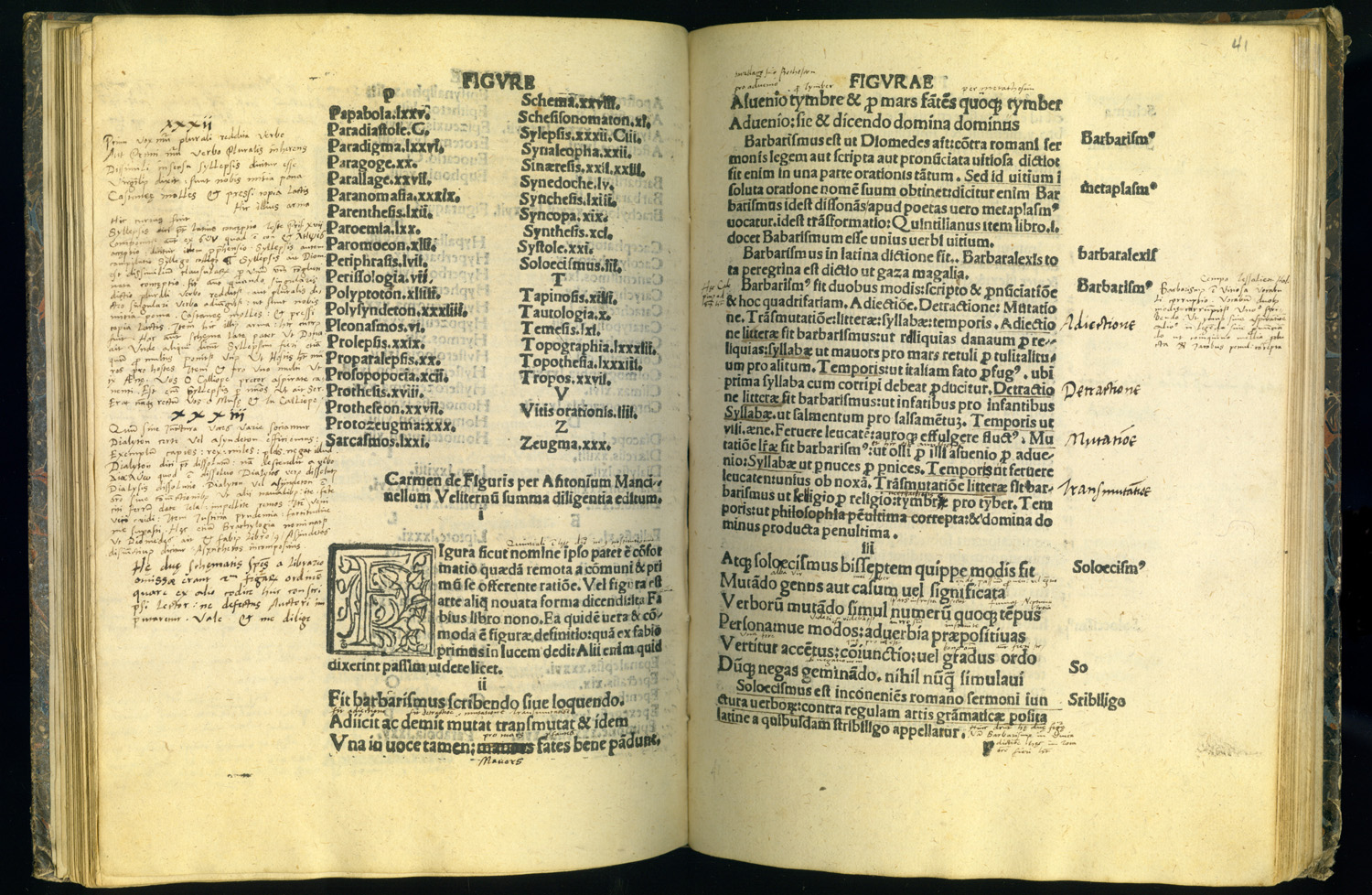

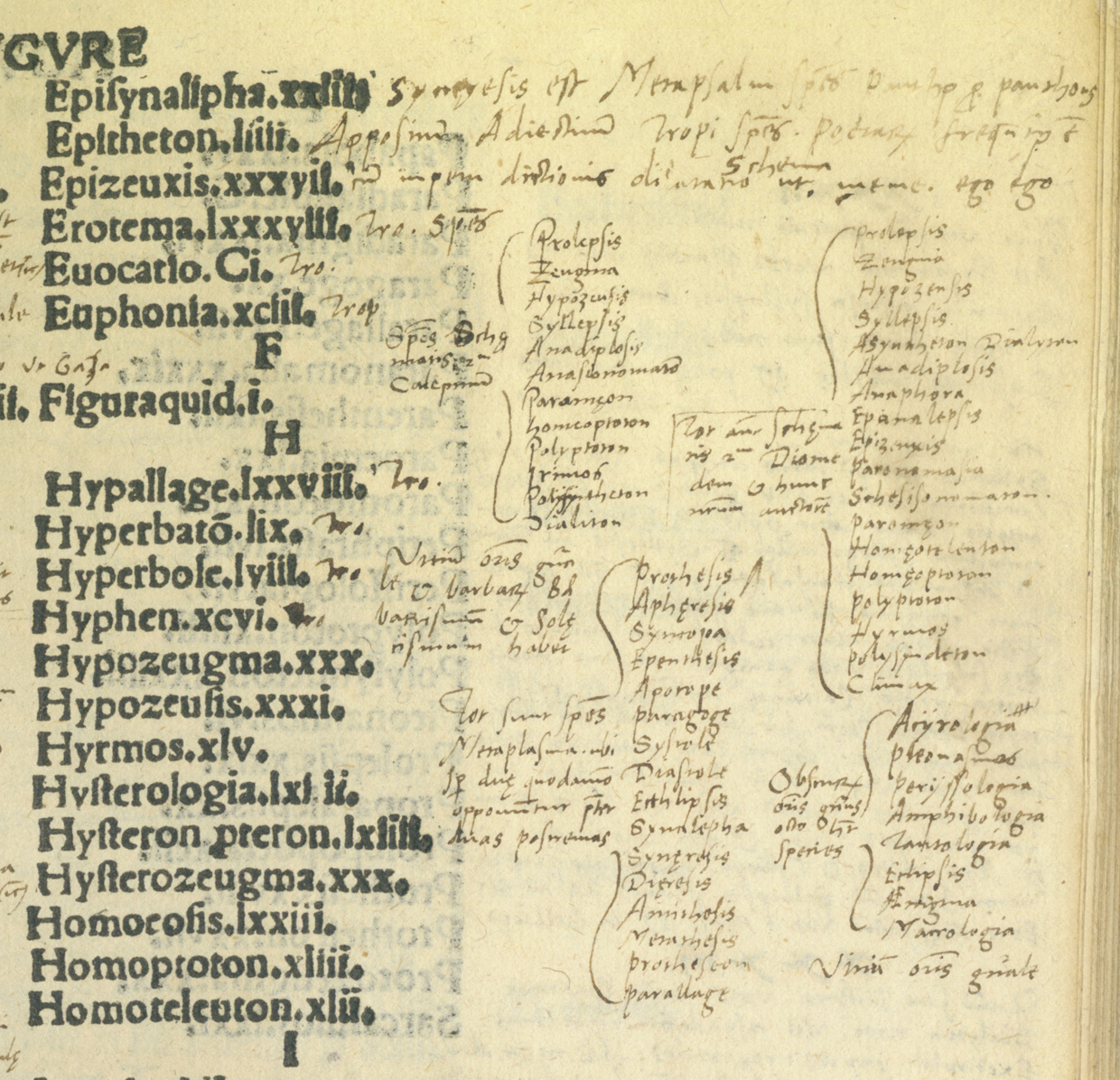

Readers, too, often calmly took the imperfections of printed books in stride. They had, after all, been correcting their manuscript books for centuries; and it was an important part of a humanist education to learn to be critical of received texts, that is, to look for errors to correct. A copy of Mancinelli's Verses on the Figures of Speech (Carmen de figuris) now at the Newberry Library was heavily annotated by a humanist reader. At one point the reader remarked in the narrow bottom margin, "Two articles, those on Sylepsis and Dialyton, are missing here. For lack of space at this point you will find them transcribed at the beginning of this book. Farewell." (15) Turning back to the first page of the treatise, we find these two articles fully transcribed in the ample left margin, and then another note to future readers:

These two articles were omitted by the printer at the place in order where they belonged, and so I have supplied them from another source. The Reader. Nor is this omission to be ascribed to the author. Farewell, and love me. (16)

This personable reader was fully capable of finding another edition of Mancinelli in order to correct the printed text he owned, just as he added hundreds of lines of notes from other authors on the figures of speech. He seems only mildly annoyed at the trouble this caused him; but he did want other readers (his students, perhaps?) to be clear that the fault, if fault must be found, was that of the printer.

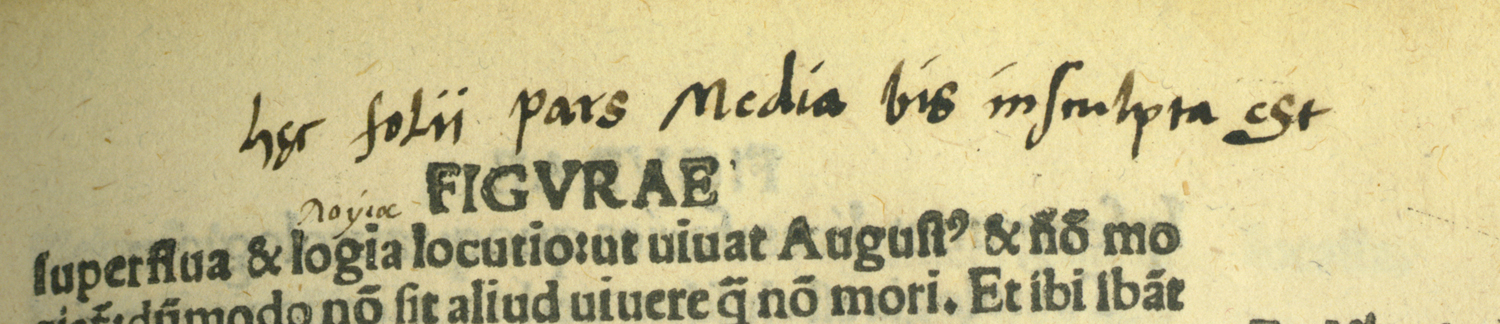

In this particular case, in fact, the printer made a monumentally stupid error, repeating one entire page from the second sheet of a gathering on the first sheet of the next gathering and then necessarily leaving out an entire page. For such an egregious error to have occurred, all the text must have been set correctly; but one typeset form was misplaced and a different one mislabeled and inserted in its place. In some copies, moreover, the printer has glossed over the error by changing the signature mark on the offending page (but not changing the text!), making it clear that he preferred to hide his error rather than correct it. The alert Newberry reader noticed not only the omission but the duplication too, and marked it: "This half-part of a leaf [i.e. one page] is printed twice." (17)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (14) Many authors discussed and criticized the mechanics of printing; see Monfasani 1988b, 17-22; Richardson 1994, 10-12 and 1999, 78-80. Grammarians in particular continued to address the matter of typographical errors and corrections; in addition to the Pellisson passage cited above, see Cantalicio 1512, fol. A3r; Bonfini 1533, fols. 3r-v and 55v-56r.

- (15) Mancinelli 1498c, Newberry copy, fol. F6r: Omissae sunt hic duae figuae Syllepsis et Dialyton quas propter spatii indigentiam in principio huius libri conspicies. Vale.

- (16) Ibid., fol E8v: Hae duae schematis species a librario omissae erant extra figurarum ordinem quare ex alio codice huic conferi posui. Lector. Ne defectus auctori imputaret. Vale. Et me dilige.

- (17) Ibid., fol. F3r (but signed F2 like the previous leaf): Haec folii pars media bis inscripta est. The book is a quarto gathered in eights, with two sheets per gathering. The page in question, E8 recto, was repeated, appearing in its correct place but also in place of F3 recto, which is missing entirely. Compare the Uppsala copy, on the General Microfilm Corp. version, where the signature mark Fii on the repeated page (already an error) is corrected to Fiii but the text is not fixed. Further on readers' tolerance of errors, Taurant-Boulicaut 2003, esp. 111-114.