2.19 Kaspar Schoppe, Master Anthologizer

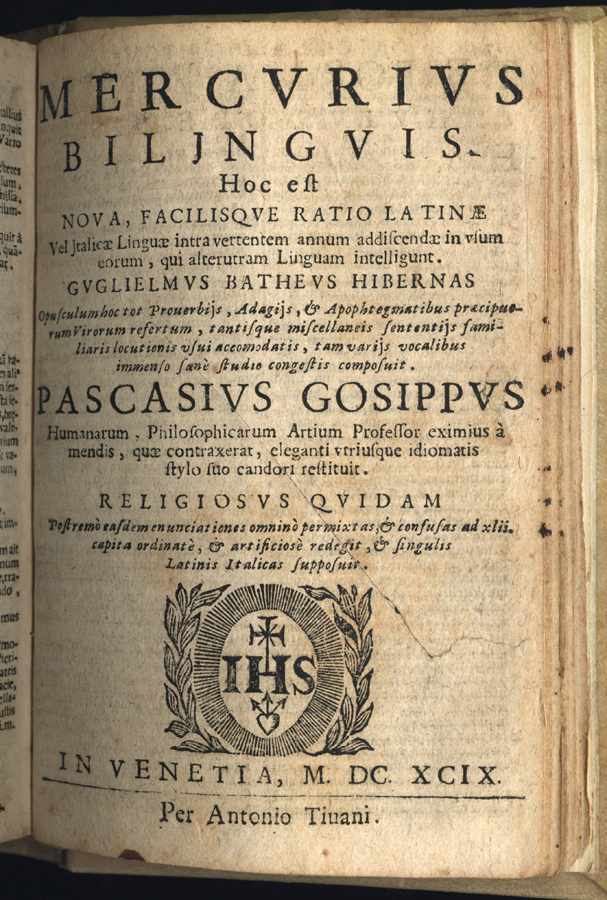

Without attempting to follow the fate of Erasmus's several collections of sayings in detail, we can see the result of this process of accumulation and anthologizing by jumping forward to the end of our period and looking at a textbook collection of sayings by Kaspar Schoppe (1576-1649), a German-born humanist whose career was largely spent at the University of Padua. Schoppe is not now best known for his textbooks, published under the pseudonym Pascasius Grosippus, but rather for controversial works of political theory and ecclesiology, especially his writings against Protestants and Jesuits. Like Erasmus, however, he was a skillful popularizer, polemicist, and packager of books for students; and his textbooks went through many editions.

Schoppe's Mercurius bilinguis, first published at Milan in 1628, was, according to its subtitle, a new and easy method for learning either Latin or Italian within one year. The "method" consisted of mastering exactly 1,141 short sayings arranged under forty-two broad subject heads. This method was not in fact new, since it had been used extensively in Northern Europe for decades, though it was still relatively untested in Italy at the period. (113) Schoppe begins with catechism rubrics, "On God and some of his attributes," and "On the passion of Christ." These are strictly orthodox in theological content, starting with the Trinity and the Eucharist so as to establish for the Italian market that the work is not in any way Protestant. There follow several other groups suggested by the experience of the Counter-Reformation Church, so: "On the titles of various ministers of the church and their charges," and "On Scripture, preaching, and penance." The anthology then goes on to traditional moral subjects such as "On obedience and reverence for elders and respect for rulers," or "On preserving love, concord, and a calm demeanor with your neighbor." Further along, there are more objective, encyclopedic categories: "On the liberal arts and sciences," "On medicine and disease," and the like. The collection concludes with one hundred witty sayings that can be used to counter detractors or critics.

This choice of subjects betrays considerable ambition. The sayings were intended to cover a variety of facts, linguistic usages, and rhetorical situations; to inculcate religious and moral concepts; and to drill students in various specialized vocabularies. Many phrases are not proverbs at all, but merely conversational or compositional usages, a fact noted with advertiser's pride on the title pages of some editions: "This work collects many proverbs, adages and apopthegmata of famous men, as well as many miscellaneous phrases adapted to everyday use." (114) Schoppe's preface told the reader that his book contains well chosen vocabulary of three types: quotidiana or everyday words; fundamentalia or root-words from which many derivatives can be learned; and rara, choice and unusual words. The second-category words are particularly important for drilling because they provide the broadest understanding of many cognates. Anthologizing of this wide-ranging sort goes back to medieval practices. In humanist pedagogy it was often presented as a method of learning conversational Latin. The sayings came from many sources but they were not attributed to their authors or contextualized in any way beyond the subject categorization. Schoppe banished Erasmus's insistence on nuanced, historical and philological context from the elementary classroom and replaced it with a rigid Counter-Reformation orthodoxy. (115) He presented the sayings as the raw material for grammatical analysis and composition, much as the Cato had been used in medieval schools.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (113) On the English textbooks for language study which may well have been models for Schoppe, Wyatt 2005, esp. 163-180. On his influence in Italy, Bianchi 1995, 806-807.

- (114) Schoppe 1698.

- (115) On the perceived need for strict orthodoxy at the elementary level, Marchetti 1975, 212-215.