2.11 Humanist Critiques of the Donat

It is likely that Calfurnio would have numbered the Donat in this same company of basic books that taught Latin falsely. Indeed the Donat may very well be what he meant by "foolish primers" (insulsa rudimenta). Although deeply ingrained in the traditional curriculum, the Donat proved problematical for many humanist teachers. At first they complained primarily about its style -- limping prose stuffed with odd words, many of them medieval and not classical. This general concern had motivated the work of Guarino and Perotti. (66) Later teachers also criticized Ianua as too difficult for beginners to understand. This change in critique probably reflects the changing way the Donat was used in the classroom. Medieval students had parroted the verses mechanically to start with and then in a second part of the course repeated them with their teacher's explication, for comprehension. The first humanists seemed to have accepted this standard method, merely chafing a little at the bad Latin that embodied it. Later humanist masters took a more integrated approach to teaching Latin; they wanted their students to learn simple, pure classical vocabulary from the start, and they did not want them to begin with an ill-comprehended text. Only if students could recognize the meaning of the text immediately could they eventually come to love the language. Robert Black sees this humanist ideal contributing to the increasing marginalization of the Donat and its relegation to the reading course; he cites as evidence the increasing number of humanist grammars after 1480 that include basic paradigms that once were learned only with the Donat. (67) At least one sixteenth-century humanist, Stefano Piazzoni (dates unknown), made a concerted effort to correct the Donat and provide it with better declensional paradigms. He seems to have had his own students in Venice in mind. (68)

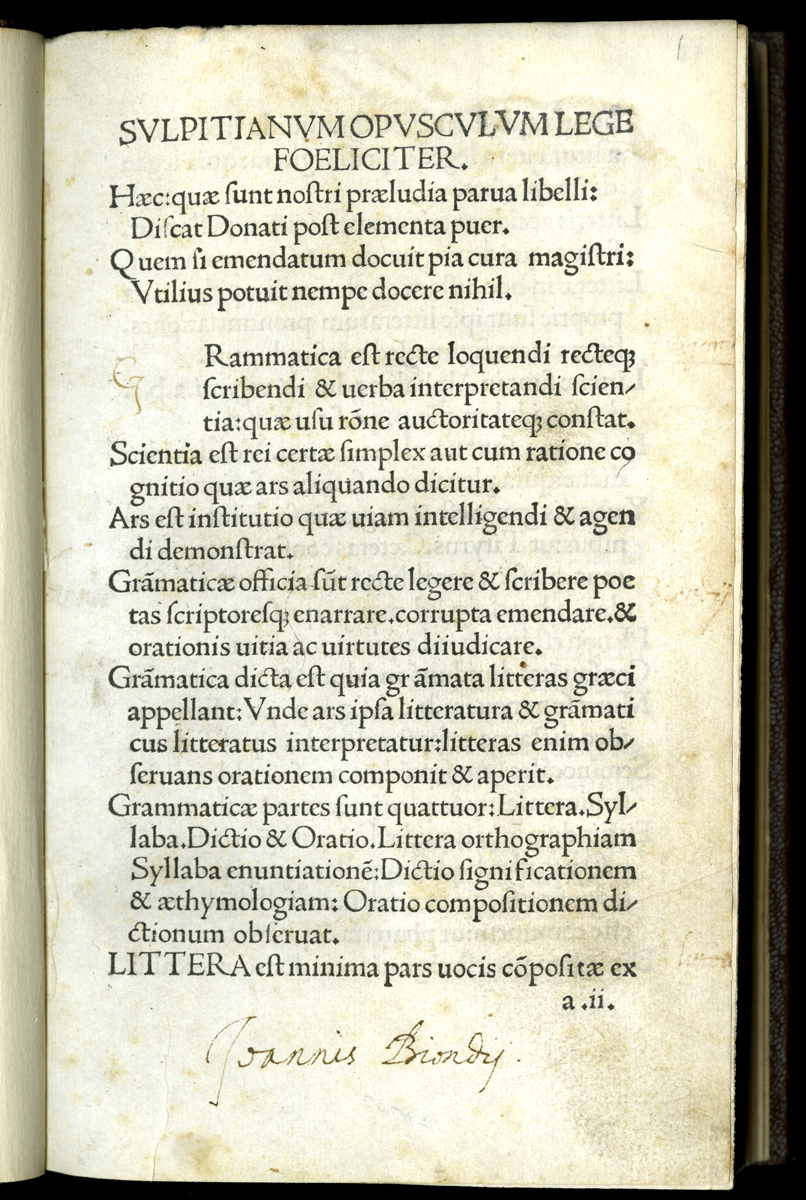

Giovanni Sulpizio (1450-ca 1513), by contrast, accepted the entrenched place of the Donat and simply created a corrective Latin grammar to follow immediately upon it. Sulpizio probably intended his work to be called Opus grammaticum, but it circulated under several other titles, most often just Regulae Sulpitii. It was often printed together with the author's work on prosody (commonly Scansiones Sulpitii) and the two works in effect cover an entire intermediate Latin grammar course. Sulpizio expressly said his book was to be given to students right after the Donat; but he assumed that they have little understanding of the inflectional paradigms. He did not give the students new paradigms to memorize, but he rehearsed the definitions of the parts of speech in an introductory poem to be memorized and then explained the regular structure of inflected forms at length. He also provided long lists of irregular forms to be memorized. In other words, he was repeating some basic material from the rote-memorized Donat but insisting it be thoroughly understood through repeated, intelligent drilling. Sulpizio made extensive use of mnemonic verses so the rules would be easier to digest. Although the book is presented in a format confusing to modern readers, with repeated prefaces, inserted passages from earlier grammarians, short reading texts, and irregular headings, it was popular with humanist teachers for its wealth of drilling materials. One of the reading texts, Sulpizio's own poem on table manners, was widely excerpted and anthologized by other authors. (69)

-(3)-combined.jpg)

It is possible that many teachers used Sulpizio more as a source book or teaching auxiliary than as a basic textbook. Giovanni Tacuino printed the two works in an unusual format in 1495, with the title Regulae Sulpitii on an otherwise blank front page and Scansione Sulpitii on the corresponding back page, effectively creating a paper wrapper for the two books if purchased and bound together. Such packaging rather effectively labels the book as work of reference. (70) Later editions styled Sulpizio's grammar accurately enough as a Grammaticae compendium. In this form the book included a chapter on the figures of speech lifted directly from Aelius Donatus' Ars maior (and attributed to him), as well as the De scansione. Sometimes the parts were pulled apart again and issued in editions designed to accompany each other. The full anthology had many editions across fifty years in Italy and was used in Northern Europe as well. (71)

Sulpizio's basic strategy -- accept the traditional Donat as unavoidable, but correct it immediately -- was adopted by many authors across the sixteenth century. But not all teachers found Sulpizio's multiplication of examples and drills a wise procedure. In Milan in 1599, Alessandro Rubini at Milan rejected several grammars then on the market and proposed his own De grammaticis insitutionibus liber. Even at this late date, he assumed his students would have memorized the Donat. His follow-up grammar gave a very limited number of clear, simple rules with a single example for each, "lest the weak minds of boys be overwhelmed by a multitude of examples." (72) From this stage, they would go on to memorize additional rules and examples, or better yet to apply them directly in reading and construing proverbs and moral sayings.

This practical development, denigrating the Donat by marginalizing it and minimizing its influence, was paralleled in the rhetoric of humanist teachers, who increasingly condemned the way in which the Donat supposedly destroyed any possible enjoyment of or appreciation for the Latin language. In the context of just such an exhortation to make Latin admirable to beginners, Francesco Priscianese (1495-1549) recommended his own short introductory grammar as a substitute for the Donat:

And the Donat too (to speak freely the truth and what, as I believe, every good man would say who had thought about it for a while) is far too dry a thing for real beginners, and too weak, and (what is most important) too difficult, both for its language, which no one understands without a translator, and also for the material treated in difficult fashion, out of order, and strangely. So much so that one can almost say that he who knows the Donat, unless he already knew a great deal of what he now knows beforehand, knows nothing at all, or rather that if he does know something, does not know what he knows. (73)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (66) Jensen 2001, 117-118.

- (67) Black 2001, 60.

- (68) There were several revisions of this work and many editions especially of a so-called secunda editio; see bibliography for editions I have examined. To my knowledge there is no study of Piazzoni.

- (69) Pecci 1912, 33-45; Scaccia Scarafoni 1954, 3-7; Blasio 1986, 495-497. Sulpizio may have been at least partly responsible for the complex and confusing layouts of some editions. That of 1489 contains a particularly extensive and wittily described set of errata.

- (70) An example survives in an early binding at the University of Illinois/Urbana-Campaign. Tacuino used the same types and format for a Perotti he published in the same year, suggesting he had a comprehensive course of study in mind.

- (71) On the fifteenth-century editions see Scaccia Scarafoni 1954, 10-13. I have consulted Sulpizio1489, 1490, 1495a and b, 1500, 1504, 1507, and 1508.

- (72) Rubini 1599 quoted in Turchini 1996, 316: ne exemplorum multitudine imbecilla puerorum mens obrueretur.

- (73) Priscianese 1559: Et il Donato ancora (per dire liberamente il vero, & quel, che io credo, che ogni huomo da bene direbbe, che punto sopra pensato vi havesse) è una cosa per li primi principianti troppa asciuta, troppo debole, & quel, che più importa troppo difficile: sì per la lingua, che da niuno s'intende senza interprete; sì ancora per la materia difficilmente trattata, & in molte parti impertinente, & strana. Tal che si può quasi dire, che chi sa il Donato, non intendendo massimamente nulla di quel, che sa, non sappia nulla. o se pure è sa qualche cosa, non sappia di saperla. The first edition of 1545 and a reissue with an altered title page date of 1545 are extremely rare, but see Redig de Campos 1939, 171; on Priscianese's pedagogical stance, Grendler 1989, 186-187.