2.09 A Best Seller: Niccolò Perotti

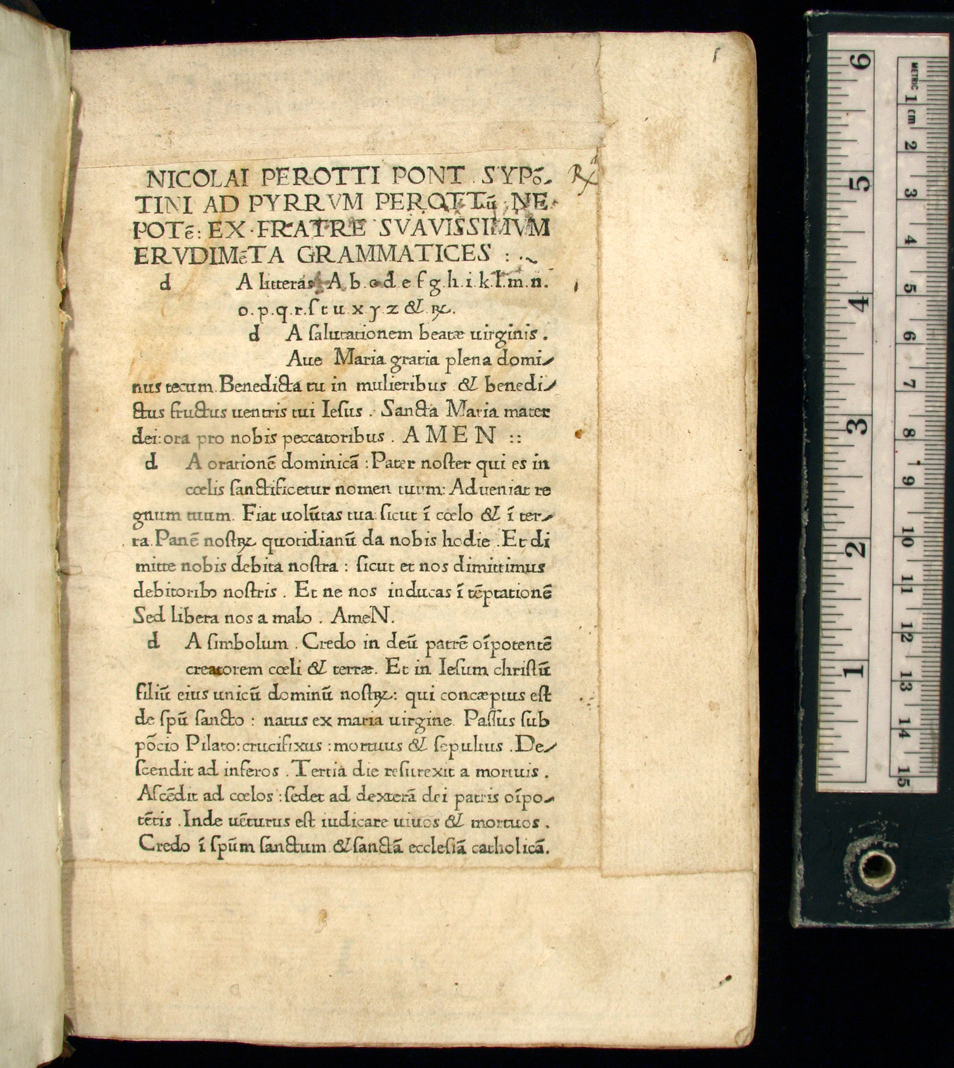

Niccolò Perotti's Rudimenta grammatices was a longer and more ambitious work than Guarino's and proposed a more significant substitution for the Doctrinale. It was the most successful Latin grammar authored in the fifteenth century. (48) Perotti begins with the usual presentations of morphology and syntax, employing mostly classical examples, and then goes on to a section on letter-writing which is actually an ambitious introduction to stylistics. Letter writing had long been the excuse for Italian schoolmasters to teach Latin style, but Perotti broke with the formulaic medieval tradition of ars dictaminis and presented the letter as an opportunity to master proper Ciceronian Latin. (49) Perotti's approach to grammar -- as a discipline that embraces morphology, syntax, and stylistics in one integrated course -- would set the measure for grammarians' marketing ambitions for several centuries. From Perotti onward, many publishers and printers looked to produce packages of grammatical texts that would either embrace an entire course of grammatical study or else correspond to parts of an integrated grammar course. (50)

Perotti also attempted to enliven the course with direct addresses to the student. Even more remarkably he claimed to abandon the medieval notion that grammatical rules are worth memorizing in and of themselves. He wanted his students to master classical style through the analysis of classical usage. To this end he defined grammar in a new way, as the art of speaking and writing well based on the observation of writers and poets worth imitating, especially the authors from Cicero to Pliny the Younger. (51) Perotti was influenced by the resounding success of the Elegantiae of Lorenzo Valla (1406-1457). Valla's learned and truculent notes on classical usage were first published in 1439 and were widely admired and used by the time Perotti, a student of Valla's, penned his grammar in 1468. Most humanist grammarians after Perotti paid lip service to this ostensibly empirical approach wherein the rules were derived from classical usage; most also gave their students endless rules to memorize. (52)

More than rules, Perotti invited his students to memorize long lists of words that occur in classical literature. We know from early annotations in editions of Perotti, moreover, that these vocabulary lists were attractive and useful. These sections of the grammar served as hooks on which owners of Perotti's book could hang notes from their own readings of classical authors. Annotations of this sort effectively rewrote the grammar book, making it over from a standard-issue word list into a personalized dictionary of usage as observed by the individual humanist reader. (53)

In their work of annotating Perotti, readers were helped along by the format of the printed book, although it is clear that Perotti's own manuscript fair copy was formatted for study and consultation in an even more thorough way than the earliest editions. (54) Perotti numbered the rules in each section of his grammar and used other mnemonic devices derived from teaching practice. (55) Printers dealt with these innovations with differing degrees of success. Early editions used broad margins and centered, all-caps section heads to imitate the spacious look of humanist manuscripts. This was true whether the printed book was in quarto, imitating small-format manuscript schoolbooks, or in folio, more closely resembling larger and more luxurious humanist manuscripts. The numbering of the rules was emphasized by centering even simple heads like "First rule on supines," "Second rule," etc. (56)

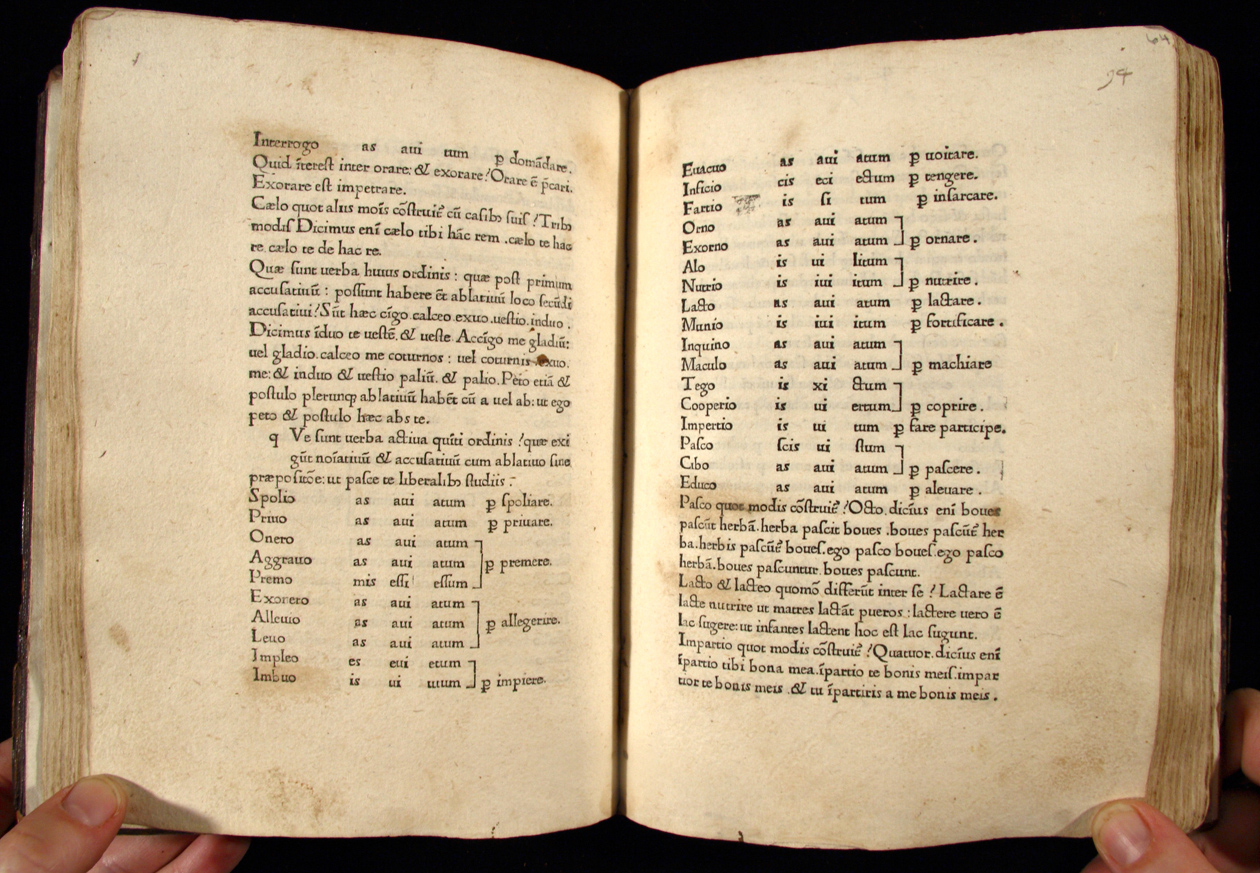

Early printers set up Perotti's long lists of vocabulary words in columns that clarify their inflectional patterns, variable roots, and meanings. For example, Perotti invited his students to memorize forty-five third declension transitive deponent verbs. He placed a tabulated list of them within the text. It gives the first person singular in present, perfect, and past perfect form and an equivalent meaning for each verb. In one early quarto edition this tabulated list occupies almost two full pages. The same layout in large-format editions could take up well over a folio page. Such layouts, of course, were prodigal of paper and resulted in relatively bulky and expensive books. (57)

More economical editions of Perotti began to appear around 1480, typically using smaller type and closer settings on quarto pages. This style never entirely replaced the earlier, more spacious editions, but the general trend was to abandon the humanist manuscript ideal in favor of denser, more utilitarian layouts. There is little doubt that the move to smaller formats was market-driven; booksellers wanted to have more than one version on offer. (58)

Instead of centering the heading for each rule, the cheaper editions set the text in solid paragraphs and simply indicated the start of each rule with a section or paragraph mark ( ¶ ). They preserved the tabulated word lists, but sometimes squeezed them in, using far less white space. (59) Almost immediately after Perotti's death, moreover, editions began to appear in black-letter types instead of the romans that more closely imitated humanist manuscripts. Other printers mixed roman and black-letter. Such editions appear first at Reggio Emilia, Milan and Rome. After the turn of the century, some Venetian editions also appear with mixed black-letter and roman. The trend toward more economical editions probably reflects the increasingly widespread use of Perotti in classrooms. The cheapening of the book culminated in a Florentine edition of 1543 in which the Giunta firm, which usually turned out handsome products, presented Perotti in a particularly crowded and homely layout. They used cracked and worn woodblocks, badly locked up forms, and sloppy inking.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (48) The Rudimenta went through hundreds of editions in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In France in the sixteenth century "Perot" became a synonym for an elementary Latin grammar, like "Donat" in English or German. See Colombat 1998, 78-79; Jensen 1998, 251; Milway 2000, 137.

- (49) Percival 1981; Lombardi 1991, 123-128; Worstbrock 2001, 72; Black 2001, 355-359. Percival's essay appeared in a special issue of Res Publica Litterarum 4(1981) devoted entirely to the figure of Perotti. On letter writing as a formal study, Witt 2000, 16-18,182-185, 310-311.

- (50) A good example of a grammar master following Perotti's lead in the next century is Lucio Giovanni Scoppa, who authored vocabulary study books, a letter-writing manual, a fulsome grammar and an epitome of grammar; see Fuiano 1971, 41-53.

- (51) Percival 1981, 237; Lombardi 1991, 124; Jensen 1996a, 68-70; Worstbrock 2001, esp. 73-78; Black 2001, 134-138.

- (52) It is most explicit as an ideal in the preface and afterward to Pilade 1543 by Lorenzo Cerreto. See also Grendler 1989, 170-171; Rizzo and De Nonno 1997, 1584 and 1607; on empirical grammars, see also sections 5.02, 5.03, and 5.05.

- (53) For example a copy of Perotti 1474, one of the earliest printed editions, now at the Marciana is annotated throughout, but heavily only in sections that detail differentiae; further on the importance of vocabulary study in humanist grammar, Jensen 1998, 257-261; Trovato 1994, 28.

- (54) Mercati 1925, 131-132 and tav. IV, identified an autograph marked for the first edition of 1473; Lombardi 1991, esp. 137-148, studied this manuscript from the point of view of the printer's work.

- (55) Black 2001, 135.

- (56) De supinis prima regula ... Secunda regula, Treviso 1476, fol. 28v. For formats, compare Perotti 1474, 1476a, 1476b,1478, 1480, 1485 and 1488.

- (57) In quarto: Perotti 1476a, fol. k3v-4v] = 79v-80v. In folio: Perotti 1478, g1v-g2r = 60v-51r and Perotti 1480, fol. g1r-g2v = 48v-49.

- (58) As did the Padua bookstore described by Fulin 1882b, 396-400.

- (59) Perotti 1501; compare Perotti 1497 and 1508 which have very crowded pages but relatively generous tabulations.