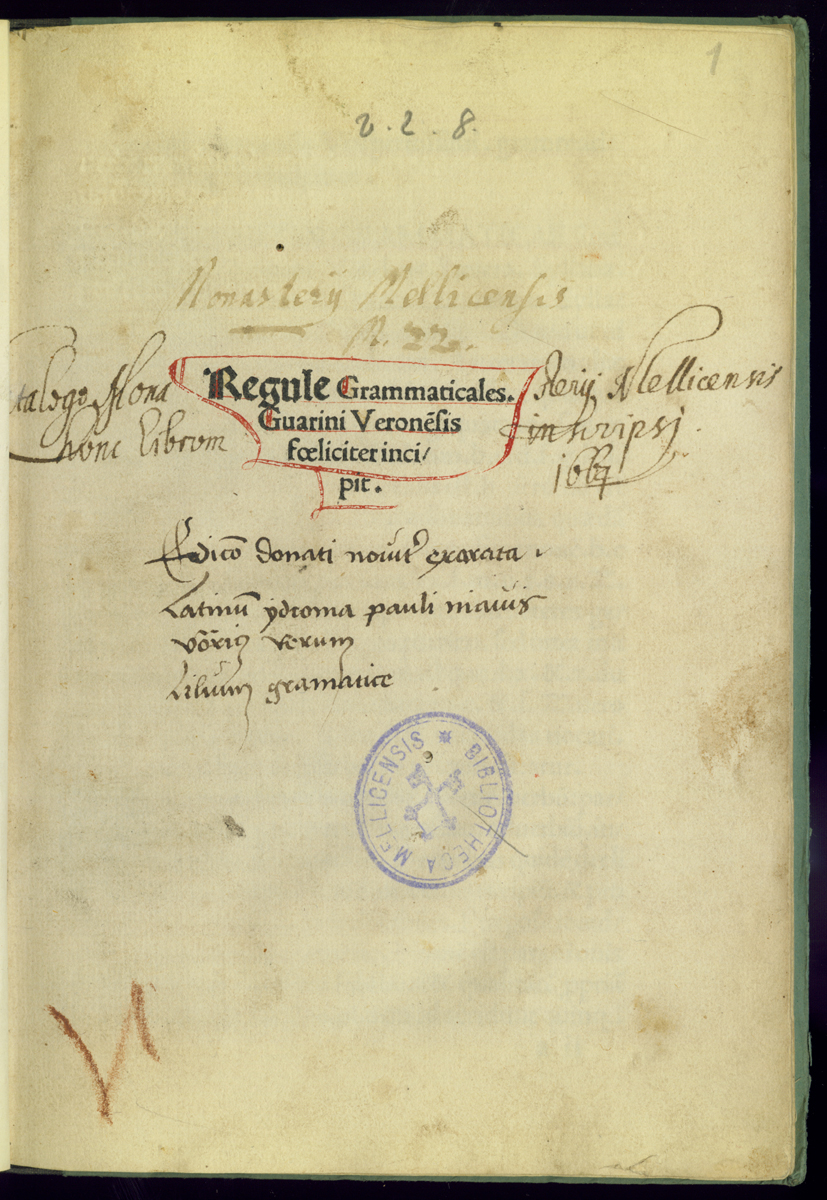

2.07 Guarino Guarini of Verona

The practical response of the Italian humanists was to author new grammars for the elementary and intermediate Latin course based on their own teaching. Pilade himself had attempted this before authoring a detailed critique of everything he found objectionable in the Doctrinale. (33) The most influential of the new intermediate grammars were those of Guarino Guarini Veronese (1374-1460) and Niccolò Perotti (1430 -1480). Guarino began work on his grammar textbook in the second decade of the fifteenth century, designing a concise prose grammar in a deliberate attempt to counter the prolix verse of the Doctrinale. He took over and simplified descriptive terms for noun and verb morphology that had been developing for a century or more in the Italian schools and exemplified each rule with good classical examples. Guarino's grammar was praised by other humanists (many of them his own students), and it came to have wide circulation in Italy as an intermediate grammar book. (34) Like the Donat, however, the text was not stable, since before the advent of printing there was no common or vulgate text, merely versions prepared by individual teachers for their own classrooms. Writing in 1459, Guarino's son Battista complained of these elaborations and modifications. (35)

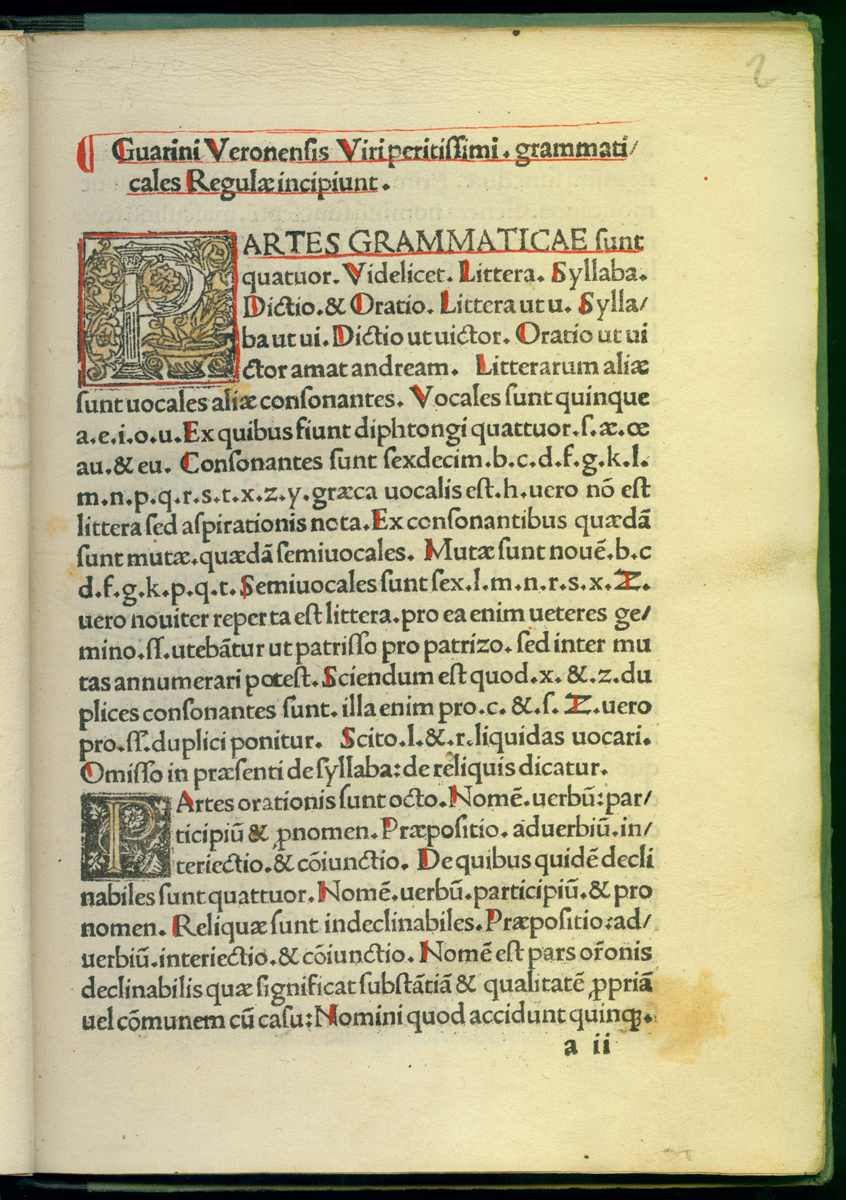

After the appearance of the first printed editions, the Guarino text stabilized somewhat. Over sixty editions are known before 1501, all but three of them printed in Italy. Typically the text began with brief, basic definitions for the parts of speech and simple noun paradigms. There followed a series of short descriptive notes for verb forms and syntax accompanied by lists of regular and irregular forms, and usually some verse-form chapters on heteroclyte nouns, orthographic conventions, and vocabulary study.

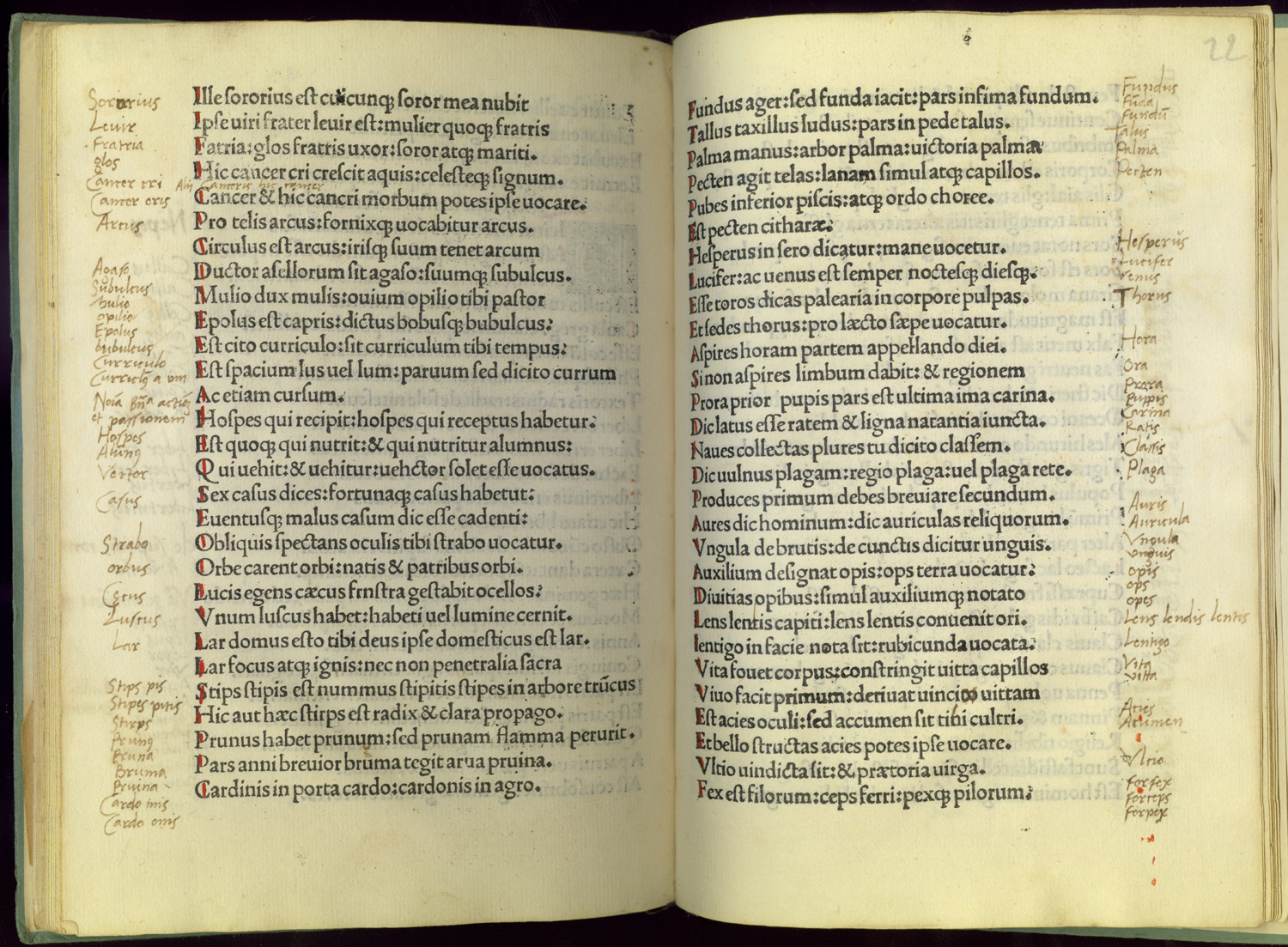

The last chapter, entitled Carmina differentialia, also circulated widely as a separate or appeared with grammar books by other authors. (36) In this form Guarino's Regulae were printed numerous times right through the sixteenth century and into the seventeenth, especially in the Veneto and Emilia-Romagna, where Guarino had spent almost all of his long career as teacher.

Typically these editions echoed Guarino's own modesty in being short, simple, relatively un-ornamented, and largely devoid of marketing prose. (37) Some printers added first page borders to dress the book like a Donat. (38) Others included Italian-language equivalents for vocabulary words, probably following the model of the bilingual Donato al senno. (39) Guarino had intended his book to be used as an introductory grammar, probably after the Donat, and this was its usual place in the sixteenth century curriculum. (40) Other early sixteenth-century publishers offered Guarino as follow-up to another first grammar book. (41)

In the fifteen fifties, Antonio Palmieri corrected and edited the received text of Guarino for the Venetian publisher Giovanni Griffio. For the first section he substituted a simple question-and-answer treatment of the parts of speech and basic noun forms. This version was copied by most later printers. Since the common printed text of Guarino's grammar was fairly summary, editors and printers throughout the sixteenth century felt free to add materials. Following some incunable editions and perhaps also in imitation of Aldo Manuzio's grammar of 1493, Palmieri added a Greek alphabet to fill out the last leaf of his 64-page booklet. (42)

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (33) Pilade 1508a and 1543 are among the many editions of his constructive grammars; 1508b is his critique of Alexander.

- (34) One small bookstore in Padua had nine copies in stock in February 1480 and received a shipment of fourteen more in April of the same year; a more established merchant in Venice handled at least thirty one copies in a single year. Fulin 1882b, 398-400; Brown 1891, 436-450. Further on these inventories, Nuovo 2003, 41-43, 128-129.

- (35) Kallendorf 2002, 272-273; see also Percival 1978; Grendler 1989, 167-170; Jensen 1996a, 66-67; Jensen 1998, 255-256; Jensen 2001, 114-115; Black 2001, 124-129.

- (36) Malaguzzi 2004, 97, 104-05; Colombat 1999, 25-26; Bersano1966, 190, 300-302.

- (37) Guarino 1474, 1493, 1506, 1507, 1516, 1545, 1564; other editions of this version appeared as late as 1642. Compare the slightly enlarged version in Guarino 1535, 1549, and 1551.

- (38) Guarino 1566, 1573, and 1616.

- (39) Guarino 1535, 1549, 1551, 1561.

- (40) Battista Guarino described his father's course; see Kallendorf 2002, 268-273. See also Grendler 1989, 188-189. The title page to the Donato construtto published at Venice in 1532 advertises that it also contains a Guarino, but this must have been a separate since it does not appear in the only surviving copies.

- (41) E.g. Antonio Putelletto's Guarino 1540 was intended to follow upon Gian Giorgio Trissino's introductory work, Trissino 1540, to the exclusion of the Donat.

- (42) Compare Guarino 1570 and 1596 which did likewise.