2.03 Pseudo-Donatus

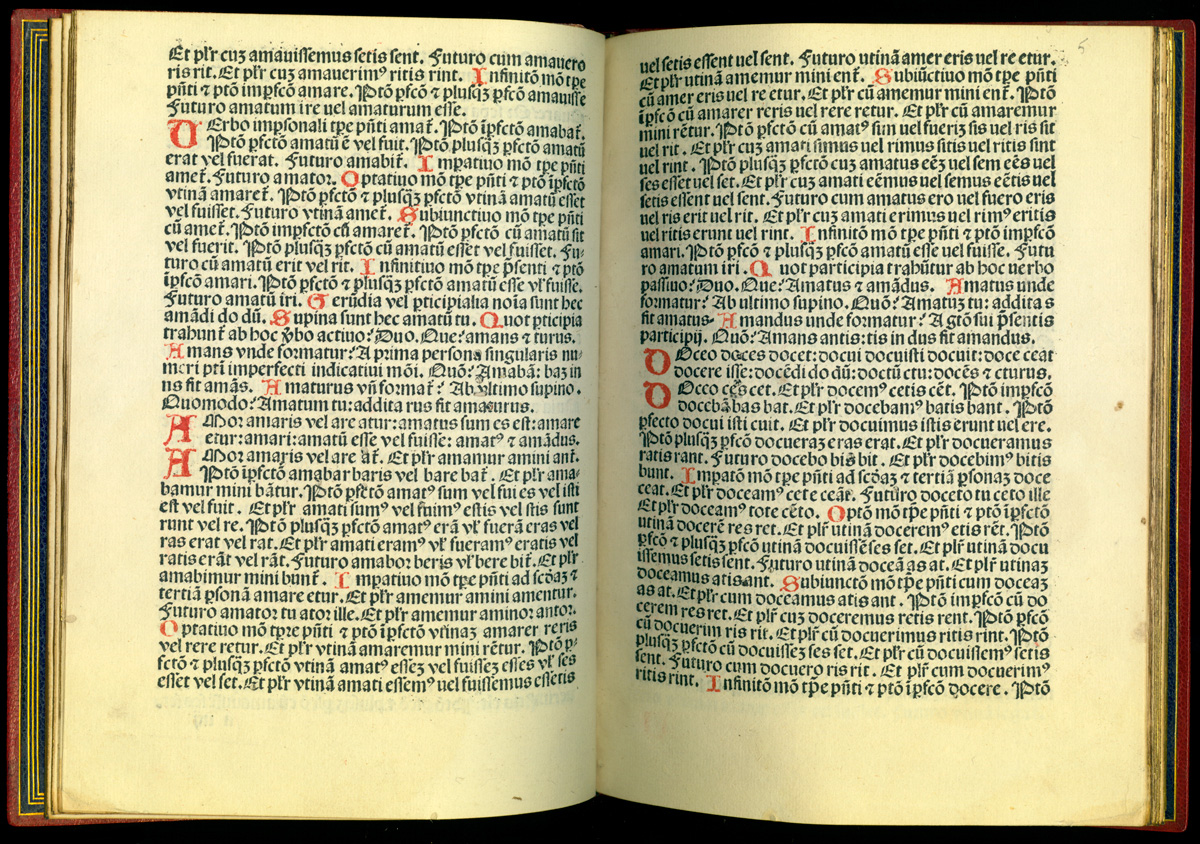

Aelius Donatus was one of the many writers between the second and the fourth century who helped preserve classical Latin for later ages by composing formal grammars. His great reputation led to the confusing situation throughout Europe that almost any basic grammar could be called a Donat. Two authentic compilations have come down to us under his name, the so-called Donatus major, a substantial treatment of morphology, and the Donatus minor or Ars minor, a question-and-answer style introduction to the same material intended for drilling basic rules. This authentic minor Donatus was widely used in medieval Europe, where beginning Latin students were often called donatistae; but by the thirteenth century it was replaced in most Italian schools by Pseudo-Donatus, a different catechetical primer with a verse preface that begins Ianua sum rudibus..., "I am a doorway for beginners..." (6)

Oddly, by most common-sense standards Pseudo-Donatus or Ianua offered students a more difficult starting point and the book was much harder going than the old Ars minor of Aelius Donatus. The catechetical or question-and-answer portions of the two works are easily distinguishable. The Ars minor in the common Northern European, late medieval form starts its doctrinal section, "How many parts of speech are there? Eight, that is, the noun, the pronoun...." (7) The Ianua, after the verse prologue, begins more abruptly, "What part of speech is poet? It is a noun. How so a noun? Because it signifies a substance..." (8) Both texts, jump into abstract grammatical terminology from the start. But the Italian Donat does so completely without explanation, while the work of Aelius Donatus, composed in the late ancient world for Latin speakers, at least tried to move in a logical fashion from general concepts to more specialized ones. In fact, the Ianua would be criticized throughout the humanist period for its unfriendliness to beginners; but it probably was invented with the opposite intention in mind, to make the first part of the course more concrete. While Aelius Donatus's Ars minor was a brief sketch of grammatical concepts for students who already spoke some form of Latin, the Italian Donat was originally a drilling book that went into considerable detail for students coming to the language for the first time. (9)

The manuscript tradition of Ianua in has been explored in depth by Robert Black and Gabriella Pomaro. (10) Surviving manuscripts are few, but in outline the history of the text is clear. By the fourteenth century Ianua dominated the Italian pedagogical landscape, virtually to the exclusion of the genuine work of Aelius Donatus and most other beginning grammars. (11) But as Black and Pomaro have demonstrated, it was not a stable text. In origin, it was a fulsome drilling text that rehearsed all standard forms and many irregular ones. It could be stuffed full of all kinds of examples and mnemonic verses, depending on the needs of the teacher and the level of study. In the thirteenth century it may have been intended as more of an intermediate than a beginner's grammar, but by the fifteenth century it had been substantially abbreviated and definitively took on the role it would have in the age of print, as the first introduction to Latin reading. Black explains this development as a byproduct of the increasing differentiation of the school curriculum. As grammar masters more and more concentrated on intermediate Latin instruction, they abandoned the Donat to teachers of reading, whose mission was to instruct the students in the alphabet, prayers, and deciphering and memorizing texts. More and more, then, the Donat became a skeleton grammar, a series of rules to be memorized without much immediate understanding or application. For students who went on with the Latin course it provided the basic terms and paradigms, but little more; for many others it was in fact the last Latin text they would ever see. In the course of the fifteenth century it seems increasingly to have been relegated to this minor role. (12)

Whether as a last text in the basic reading course or as a useful summary grammar, it is clear that the Donat in Italy was also a diagnostic text. It stood at the point when parents and teachers decided that a few beginning students would go on to become Latinists, while the largest number of pupils were weeded out. These latter students abandoned the formal Latin course, and either did not study further or went on to study practical matters like business math. (13) It was in this diagnostic role that the Donat entered the age of printing. It would necessarily change again in the sixteenth century. As humanists increasingly insisted upon the role of Latin as an instrument of power and beauty, they would become increasingly ill content with a text like the Donat that presented Latin grammar as a barrier to be crossed.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (6) Follak 2007, 151-152.

- (7) Partes orationis quot sunt? octo, que nomen, pronomen, ...

- (8) Poeta que pars est? nomen est. quare est nomen? quia significat substantiam...

- (9) Black 2001, 47-48.

- (10) Black 2001, 45-83.

- (11) Cervani, 400-401; see the bibliopgraphy for editions I have examined.

- (12) Black 2001, 48-62 and 2007, 44-47.

- (13) Ortalli 1993, 60-65.