1.16 Vocabulary Drills and General Rules

One of the major achievements of the humanists in the sixteenth century was to devise and publish a broad range of auxiliary texts for studying the classics, from commentaries and self-study manuals to translations, dictionaries, and encyclopedias. (67) As with many other phenomena once considered fruits of the first age of printing, we now know that these reference sources, study guides, and how-to books derived from late medieval, scholastic models and from humanist philological scholarship that began well before the invention of printing. Moreover, books of the sort reached full maturity only a century after Gutenberg's press came to Italy, so they cannot rightly be said to be native to the medium of printing. As we will see repeatedly, however, the mature forms were very much a product of the market for printing. Terence provides us with good case studies for these auxiliary genres and their marketing.

Vocabulary-study exercises were derived from classroom and private annotations. Most surviving textbooks with manuscript annotation contain vocabulary-study notes made by teachers. Very likely these were dictated to students as texts were read and parsed in class. It was only a short step from annotating thoroughly to compiling the annotations in print for the use of other teachers and students. Early models of the eventual print genre were provided by little synonym dictionaries like that (ostensibly based on Cicero) known to Coluccio Salutati (1331-1406). (68) The Neapolitan grammar master Lucio Giovanni Scoppa (d. ca. 1551) provided more detailed and better documented anthologies for students early in the sixteenth century with his Collectanea in diversos auctores and Spicilegium, two aids to Latin composition with elaborate indexes. (69) Cicero and Terence, mainstays of the intermediate Latin class and so the first "difficult" authors many students would encounter, were naturals for treatment in this way. In the case of Terence the lists usually appeared in appendixes to student editions. Cicero's vocabulary was sometimes treated in separate volumes for advanced students. (70)

Latin vocabulary lists based on single authors could help first-time readers of these texts, but even more importantly they were intended to help composition students to imitate the style and usage of widely admired authors. (71) Terence was considered the best possible model for spoken Latin, so humanists like Cornelius de Schryver (1482-1558) compiled excerpts aimed specifically at helping students speak fluently. (72) Not surprisingly, the production of vocabulary and style excerpts was linked to the compilation of collections of proverbs and sayings (sententiae or dicta). Proverb collections could be Latin-only, Latin-and-vernacular, or vernacular-only anthologies. The most successful Italian author of such compilations was Niccolò Liburnio (ca. 1474-1557). Liburnio was a humanistically trained cleric, poet, and prolific translator. He worked at least briefly in the printing house of Aldo Manuzio, and composed several works on Latin and Italian stylistics. Liburnio published his first compendia of sayings in Italian in the fifteen twenties for the use of layfolk who wanted to achieve a veneer of verbal culture in the vernacular. (73) By 1537 he was assembling philosophical commonplaces from Greek and Latin writers (including Cicero and Terence) which were widely imitated. Obviously, the genre was not highly original to start with and it was easy to knock off a new collection by simply rearranging or re-titling an old one. So dicta notabilia, elegantiae, dogmata philosophica, gemmae, selectiores et puriores formulae abounded.

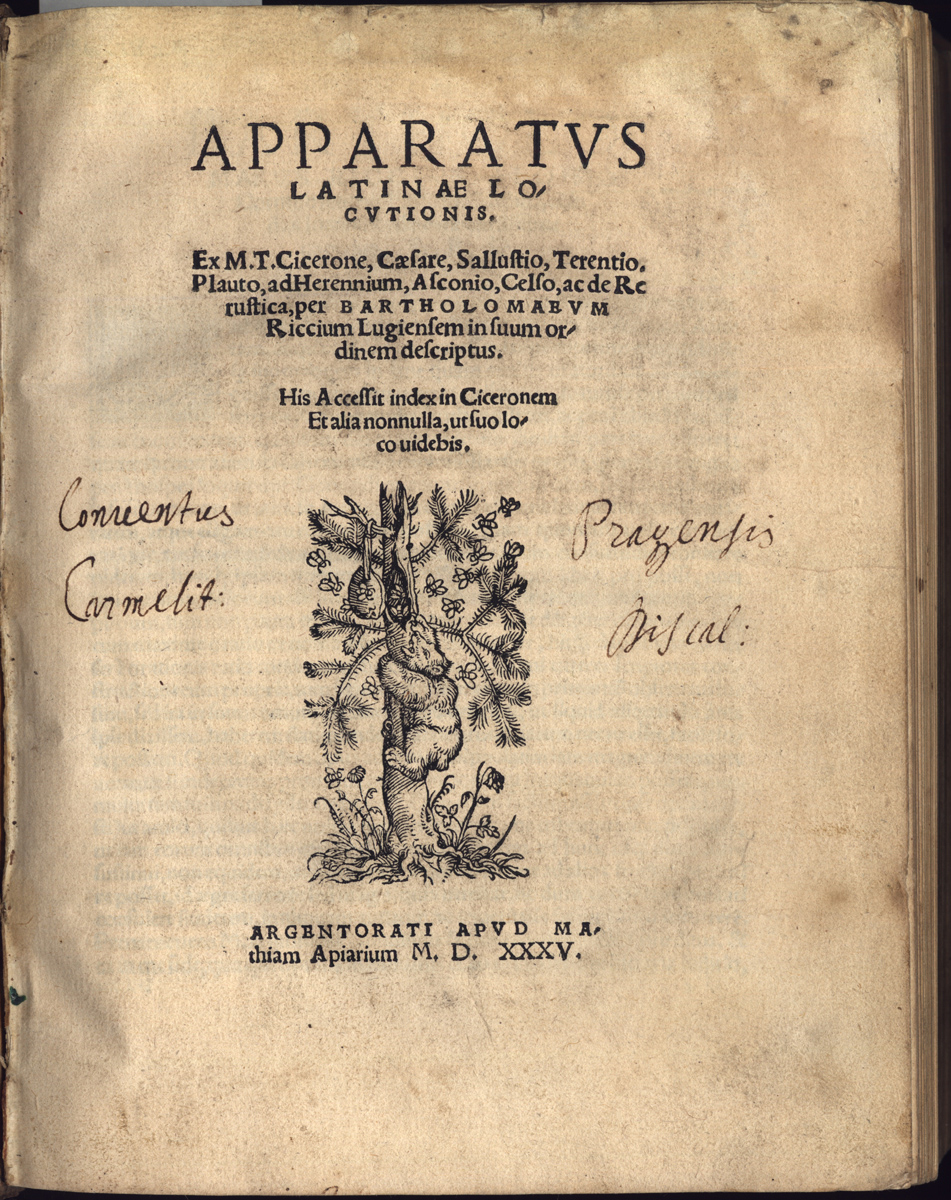

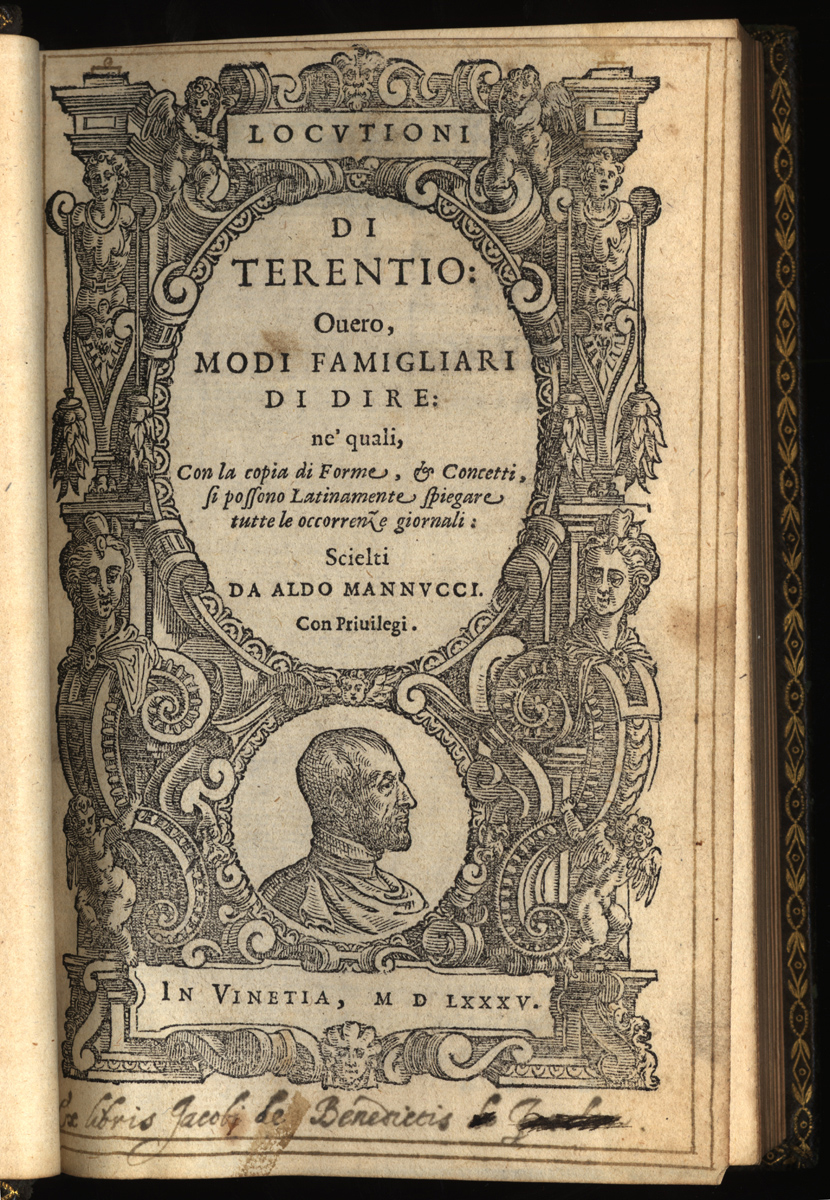

Even truly learned Latinists like Bartolomeo Ricci (1490-1560) and Aldo Manuzio the Younger (1547-1587) assembled collections of extracts from Cicero and Terence. Both men probably sent their works of the sort to press simply to make money. (74) Collections based on Cicero and Terence had especially wide currency in the Netherlands and England, where they were a staple of the educational market until the mid-seventeenth century.

NOTES

- Open Bibliography

- (67) Moss 1999, 147-149.

- (68) The Pesudo-Ciceronian Synonyma was a highly unstable text. The brief form known to Salutati, on which see Ullman, 1963, 224-225, was published in the 1480s (GW 7031 and 7032). A considerable expansion by Bartolomeo Facio (d. 1457) saw numerous editions from 1490 onward. Facio 1490 and 1519 were issued by printers who also produced textbooks of Antonio Mancinelli.

- (69) There were many editions, e.g. Scoppa 1507, 1512, 1534, 1567; see Fuiano 1971, 41-48. A good example of the kind of annotation that produced such vocabulary lists is a copy of Terence 1545 at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana, Milan, where there is also a loose sheet of notes on style and vocabulary of exactly the sort used to compile lists.

- (70) Most famously perhaps, Nizolio 1538 and many subsequent editions under the title Thesaurus Ciceronianus. Another popular and much-reprinted anthology was Cafaro 1568. On the genre, Trovato 1994, 30-32.

- (71) Both these goals are enunciated by Facio 1519, fol. 16v.

- (72) See Terence, Selections 1533a and 1533b.

- (73) Dionisotti 1962; Peirone 1968.

- (74) Ricci 1533 was a spectacularly unsuccessful speculation; see Gerini 1897, 152-153. Manuzio 1584 and 1585 were equally probably money-making projects; Deutsch 2002, 1017 found that this work was in use well into the next century.